On Feb. 23, Daria Serenko, a Moscow political activist, was finally released from a fifteen-day jail sentence.

Daria had been arrested for an Instagram post she had made in 2021 that featured “extremist” symbols associated with anti-corruption firebrand Alexei Navalny. She was exhausted. Her only wish was to get some sleep. The next day when Daria woke up from her first long and refreshing sleep in two weeks, she learned that the war on Ukraine had started.

A couple of hours later, she received a text from a friend, Ella Rossman, a feminist activist and a historian in London. The text was short and to the point: “We need to organize something.”

That “something” turned out to be one of Russia’s fastest-gowing anti-war campaigns, Feminist Anti-War Resistance (FAR). Since the organization was founded, approximately 5,000 people have shared pictures from protests, leaflets, zines, and the stickers they created. People from 112 cities took part in a FAR protest on March 8 that was dedicated to all the Ukrainian civilians killed in the war.

FAR now has more than 26,000 followers on Telegram. FAR sees itself as a horizontal organization — there is no strict hierarchy, and anyone can join and use its symbols. The only requirement is to share the organization’s values.

“Feminism as a political force cannot be on the side of a war of aggression and military occupation,” their manifesto proclaims. The manifesto has been translated to almost thirty languages, including Tatar, Chuvash, and Udmurt. FAR calls on feminists in Russia and all over the world to join peaceful demonstrations, participate in anti-war campaigns, and spread the truth about events in Ukraine.

Taking risks is part of the job

Protesting against the military operation in Ukraine has been risky from the start. On Feb. 24, more than 4,000 people were detained at anti-war demonstrations all over Russia. After jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny called for a mass demonstration on March 6, a number of political activists were arrested and put into a temporary detention center. They were suspected “using the telephone for terrorist activities.”

Even sharing information has become risky. A week after the start of the operation, Putin signed a law against sharing ”fake news” about the events in Ukraine with up to 15 years in prison for offenders. Even a simple “No to War” slogan on a t-shirt is now seen as “discreditation of Russian armed forces” and means a fine.

There is also risk of mistreatment by the authorities. This March, several young women detained at an anti-war rally reported that they were beaten and verbally humiliated at Moscow’s Brateyevo police station. The audio recording of the beatings went viral on social media.

“We constantly warn people that participating in our movement is not hundred percent safe,” says Ella Rossman, who is now one of the spokeswomen of the project. “No political activism in Russia is safe. We try our best to explain the risks and explain how the new laws work. We constantly monitor the information about arrests of our activists.”

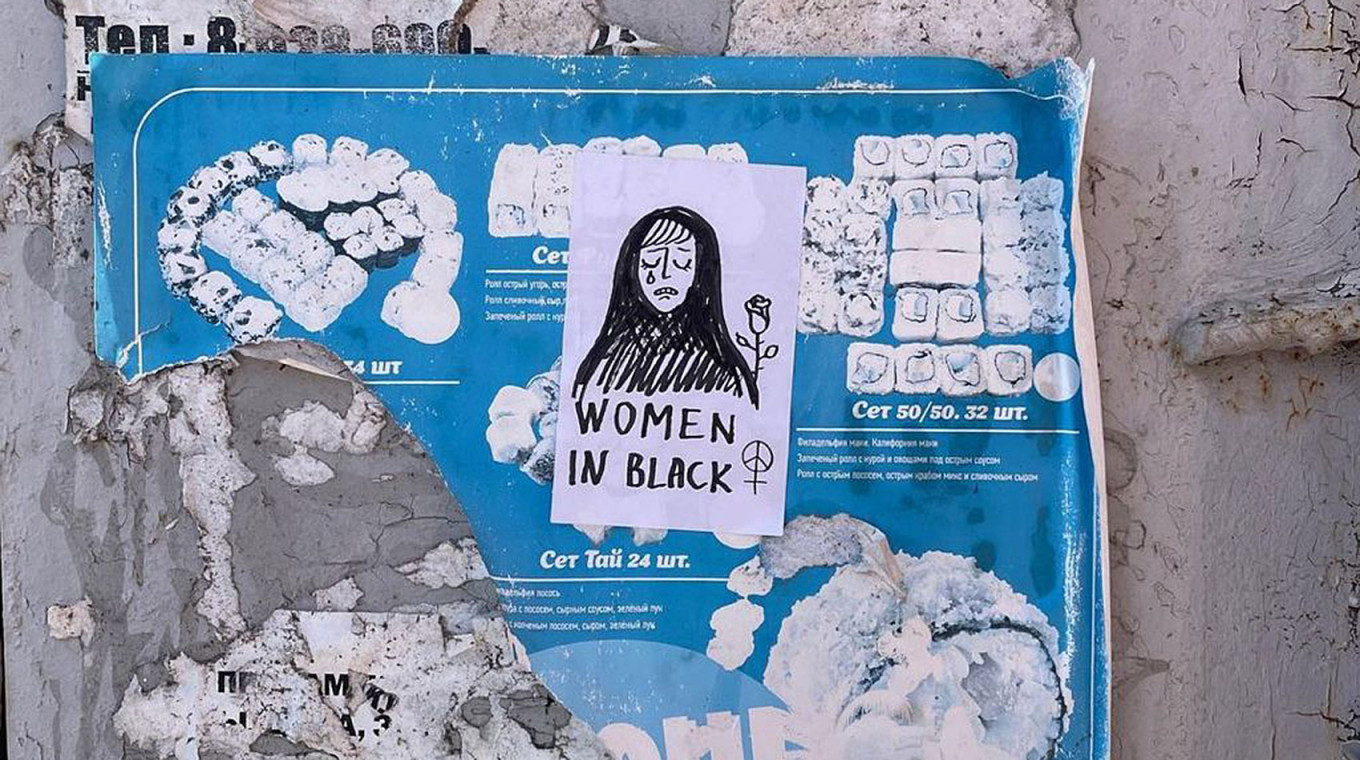

FAR gives its activists detailed instructions on cybersecurity and ways to avoid the attention of police in the streets. Every day, they come up with new ways of protesting that are still considered legal. Activists write anti-war slogans on banknotes, create art objects and install them in parks, go out wearing all black as a sign of mourning for those killed in Ukraine, hand out flowers, or simply cry in the Moscow metro.

“However,” Daria Serenko added, “the situation changes every day. What was acceptable yesterday does not work today. A week ago, you could go out wearing black and hold a white rose in your hand. Now you will be detained for that. This is what happened to our activist Anna Loginova from Yekaterinburg. She received nine days of administrative arrest.”

“We’ve had more than 100 activists who were detained or harrassed by the police,” Serenko said. “We get in touch with them as soon as possible, ask them what they need, and how we can help. We put our activists in touch with lawyers and make sure their cases get enough media attention. We also provide psychological support. We find free psychotherapists who can help if something outrageous and traumatizing happens, like what the women detained in Brateyevo went through.”

The group also has a fund to help participants who have lost or quit their jobs due to their political views.

The “feminine” face of protest

In the past few weeks, social media has been filled with comments about the “feminine face” of Russian protests. Marina Ovsyannikova, the Russian state television producer who interrupted a news broadcast with an anti-war banner, is a striking example. Daria Serenko also notes that the Russian LGBT community is also playing a large role in protest.

Ella Rossman noted that there are, of course, men involved in protests. “We get a lot of messages from men who support our movement. There is a place for everybody,” she said. “But I would say it is a definite feature of anti-war protests in Russia – there are a lot of women. And they are really very active. They picket, wear yellow and blue clothes, and spread information.”

She sees the explanation in the growth of feminism in Russia. “By my count — and I have been monitoring the feminist movement in Russia for three years as a participant and a researcher — there are now more than 45 grass-root feminist groups all over Russia. And they collaborate with each other. This is why feminists could mobilize quickly.”

She also noted that this has resulted in a “new understanding of female agency. Even though women in Russia have been politically active for years — look at the Soldiers Mothers Committee — there is a new way to look at women. A woman’s place is not the kitchen alone. Women can and need to be socially and politically active and change things they disagree with.”

Serenko and Rossman now spend eight to twelve hours a day working on FAR. Both have left Russia — Serenko left after the invasion in Ukraine started, and Rossman has lived in London since 2021.

“I am currently not in Russia, so I can reveal my name,” said Rossman. “When we started this, we thought it was very important to have participants who don’t hide their identity. It would seriously enhance our credibility, show that we are real people, and that this is not a police trap. The fact that I am abroad gives me the freedom to do certain things people in Russia can’t.”

She is aware that she probably cannot return to Russia for many years and that there are issues connected with organizing a Russian protest movement from abroad. “But I think that this is how our movement can go on no matter the circumstances, even if most activists in Russia are arrested.”

Besides, there is another advantage to a largely female protest movement. “The policemen have underestimated us for years,” an anonymous activist said. “If you throw one activist to jail, another one will take her place. Women have shown they are tremendously strong. I have always known my friends were brave. But the situation made me realize they can also remain firm and act instead of wallowing in indecision of self-pity.”

Lölja Nordic, a feminist activist who participates in FAR, notes that the increasing pressure protesters now face is meant to scare not only them, but also their coworkers, friends and relatives. “They want to terrorize you and people around you,” she says. “They want everyone to believe that having an opinion and speaking up is dangerous. That it will lead to punishment. It is important not to panic, but remember that anyone now can be detained at any moment. Prepare yourself and your family for whatever might happen. Talk to your friends and relatives about the potential risks. Discuss safety measures. Tell your family who they should call in an emergency… Plan exactly how you will help each other if someone is detained or raided.”

“I personally am not afraid,” one of the activists said. She compared current conditions to Soviet censorship. “It just surprises me how inventive people can be under such circumstances. Before the war, I would watch Soviet movies and wonder — how did they get away with it? That’s what our situation is like. Protests are getting more and more inventive. ”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.