The general view of Russian cuisine is that it is rather boring and predictable. Potatoes, cabbage, dill, turnips — and that’s about it. But if you go back a few hundred years, you can find absolutely amazing products and flavors.

For example: you can find cardoons. Do you know what a cardoon is?

You might if you spent your time happily working in your garden, growing edible cardoons. Today most of us in northern Europe and many other countries don’t know what it is. Its ancestor was the thistle. But if it is now forgotten, there was a time when the cardoon was much appreciated.

One sunny autumn day we found ourselves in an amazing place 100 km (62 miles) south of Moscow. This is the village Dvoryaninovo near Tula and the manor house of the sadly almost forgotten scientist Andrei Bolotov, the founder of Russian botany and phenomenal gardener.

Impressions from this trip had faded in the usual hustle and bustle. But another golden day autumn reminded us of those days last year when we were happy to be (almost) in the 18th century where we could harvest turnips, squash and those cardoons.

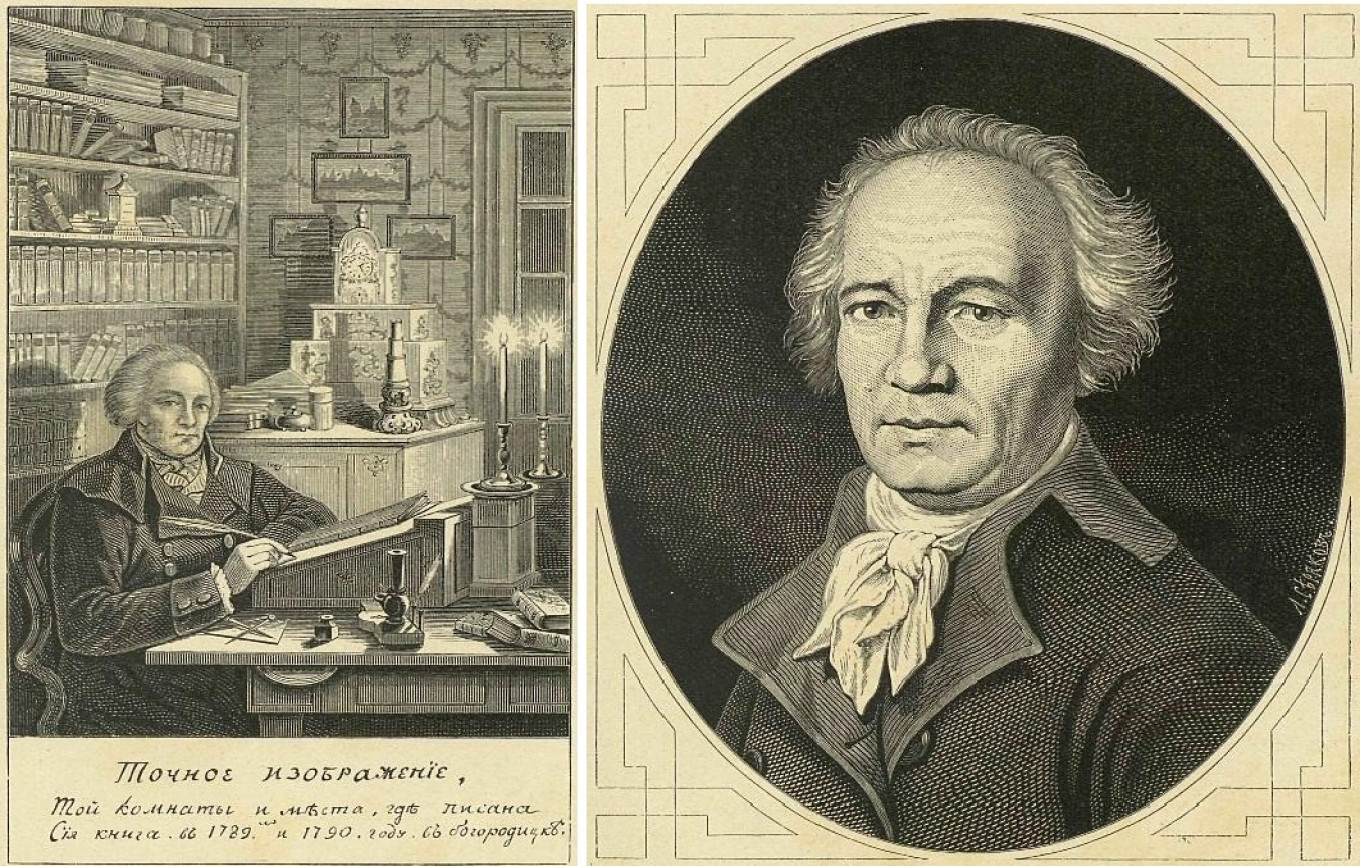

Andrei Bolotov was born in 1738. His family house didn’t survive to our days; it burnt down in 1931. An artel that made abacuses in the space had trouble with its bookkeeping, and to avoid unpleasant questions, the workers set fire to the building. The mansion was carefully reconstructed in 1988 according to drawings made by Bolotov when he was 30 years old.

But by the end of the owner's life the house was completely different: two wings, a belvedere, an art gallery, greenhouses where the scientist grew pineapples, grapes and walnuts. Built on the mountainside, the house was surrounded by a terraced garden. On the four lower terraces (out of seven) Bolotov planted apples. When they blossomed in spring, it seemed from afar that there was snow on the mountain slope.

Bolotov is an amazing example of perseverance and diligence. Every day he got up early: in summer at 3:30, in winter at 5:30. He immediately sat down at his desk to write, draw and do research. He had time for a lot of things, even to admit that he was a happy man! The scientist lived to the age of 95, and if you add up all the pages he wrote into medium-sized books, you’ll get 350 volumes. He compiled the first Russian botanical descriptions of weeds along with medicinal and cultivated plants.

He published the first article in Russia about potatoes in the journal “Economic Store” in 1770. He became acquainted with this crop in Prussia when he served as an interpreter in Königsberg during the Seven Years' War. He brought a few tubers of potatoes with him to Dvoryaninovo and planted them in the vegetable garden. Soon they had enough crops to bake potato pies. They even made “potato butter.” When peasant women were beating milk into butter, Bolotov had them add mashed potatoes (1:1). He fed his household this “potato butter” so that they would get used to the new flavor.

It was Bolotov who made potatoes and tomatoes agricultural crops in Russia. Bolotov invented a recipe for natural potato chips, which he called “potato shavings,” and studied ways to produce potato starch on an industrial scale.

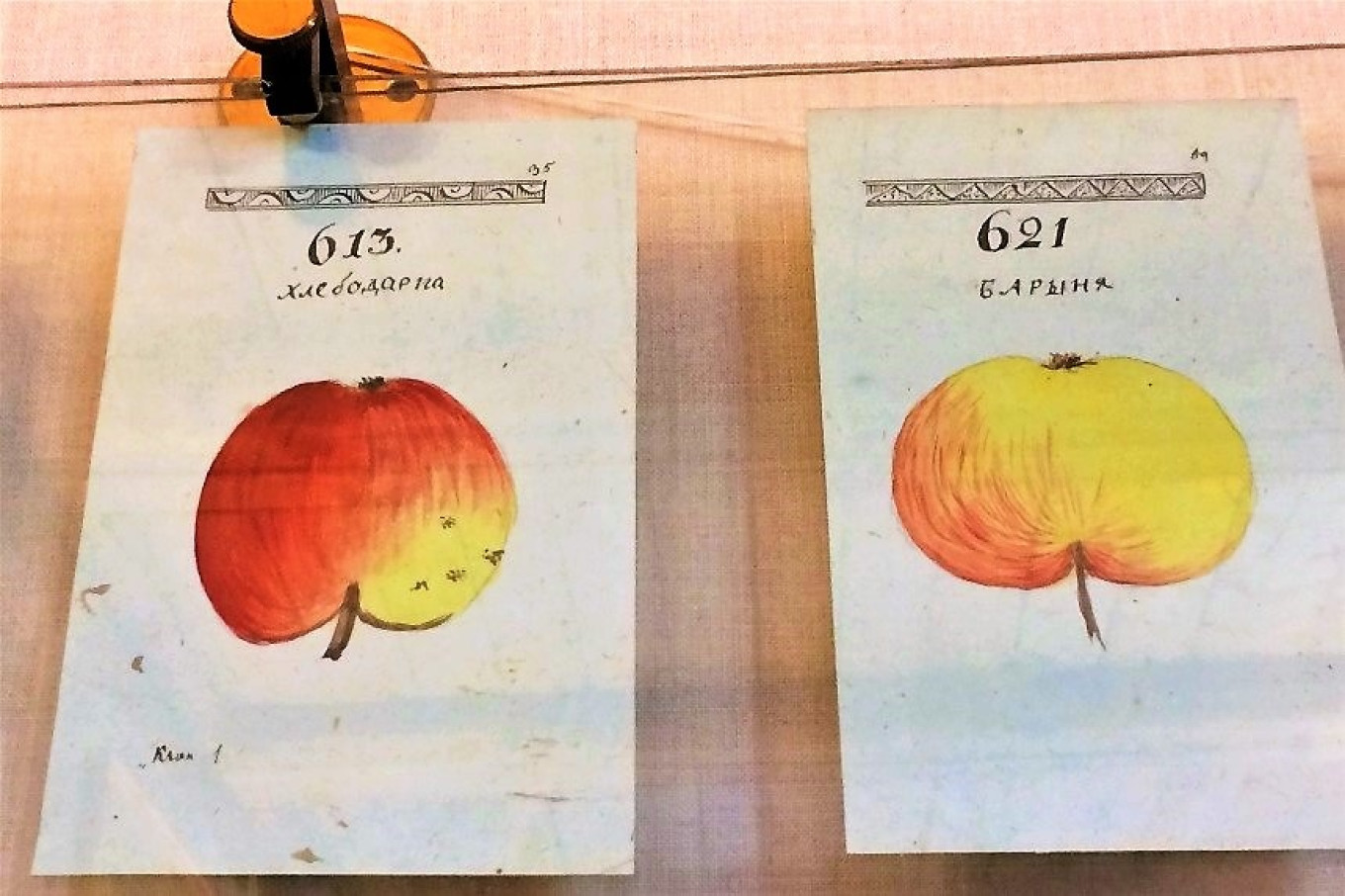

Bolotov was also the founder of the study of apples — pomology. He was the first to describe 661 varieties of apples and pears which he annoted with life-sized color drawings.

Today the best monument to Bolotov is his vegetable garden. Carefully restored by the museum staff, it contains many plants from Bolotov's time. The real discovery here is the cardoon, aka Spanish artichoke.

The cardoon is, in fact, the older brother of the artichoke, part of the same family. Their common ancestor is the thistle, the symbol of Scotland. Long ago, the beautiful thistle with its recognizable corolla was subjected to the process of selection. Attempts to develop the flowering part resulted in the artichoke; attempts to develop the stem led to the cardoon.

The seeds and sprouts of the cardoon were formerly used in Mediterranean countries as an agent for fermenting cheese. This method is still used today in the Italian regions of Abruzzo and Sardinia, where cardoons are sold in markets.

Love for artichokes in Russia began with the cardoon. They were grown not only on estates as a kind of upper-class entertainment, but also in the fields on an industrial scale.

In the 18th century specialists were even able to make artichokes into perennials. The issue sol solve was how to shelter the plants over winter. Every bush and every cardoon plant had its own plywood “house.” It was covered with leaves and the first snow so that the plant could breathe. Another technique was to dig up the artichoke, put it in a basket, and over-winter it in the cellar. During the winter the plants were carefully tended so they wouldn’t dry out or, to the contrary, rot from too much watering. In the spring the artichokes were planted outside again.

Harvesting cardoons is also a difficult task. Mature plants are tough, but unripe plants don’t taste good. To solve this problem a few days before harvesting the cardoon stalks are wrapped in paper or cloth. This “whitens” the stalks: without the sun, they turn white and retain a young, delicate flavor.

The only parts of the cardoon that are edible are the stalks, which look a bit like celery. But there the similarity ends. You can eat celery stalks raw, but cardoon stalks have to be put into water that is acidified with lemon juice. Otherwise the stalks immediately darken.

There is a secret delight in cardoons: the “heart of the cardoon” — the very bottom of the stem. This is the part that tastes most like an artichoke.

What did they make with cardoons? Salads, casseroles and soups. To make these dishes the stalks were boiled in salted water that was acidified with lemon or “in white water” — a mixture of water and milk.

Together with the museum staff, we cooked cardoons. Here is a taste of the past!

Look for cardoons at farmer’s markets and, of course, in the Mediterranean region.

Baked Cardoons

Ingredients

- 2 medium sized stalks and the “heart” of a cardoon

- 1 lemon

- 40 g (1.4 oz or 5 1/3 Tbsp) flour

- 40 g (1.4 oz or 2 2/3 Tbsp) butter

- 100 g (3.5 oz or 1 c) grated cheese

- 1 cube vegetable stock

- salt, ground black pepper to taste

Instructions

- Pour cold water into a large saucepan and squeeze in the juice of a lemon.

- Place the pot of water on the stove, salt and turn on the heat.

- Clean the stalks, removing the inedible parts (flowers, leaves and prickly hairs). Use a sharp knife to hook the strings and pull them out.

- Cut the stems into bite-sized pieces, about 3 cm (1 ½ inch), and then cut lengthwise into strips. Place them and the heart in the bowl of acidified water as you cut them.

- When all the stems are cut, drain the water and put the prepared cardoons into the boiling water. Boil for 25-30 minutes, drain when tender.

- In a small saucepan, boil 80 ml (1 /3 c) of water and dissolve the vegetable cube.

- Preheat the oven to 180°C/355°F.

- In a saucepan, melt the butter, pour in all the flour and stir. Stirring continuously, gradually pour in the vegetable stock.

- Place the cardoons in a baking dish, salt to taste. Cut the cardoon “heart" into circles and lay them on top in a single layer. Pour the sauce over everything.

- Sprinkle with grated cheese and bake in the preheated oven for about 10-15 minutes.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.