Only weeks after the head of Russia's largest bank warned that the country was at risk of "technological subjugation," two tycoons were reported to have made large investments in some of the world's most eye-catching tech projects — outside Russia.

USM Holdings, a company controlled by metals and mobile technology magnate Alisher Usmanov, has invested in Uber, the fast-growing taxi service, a spokesperson confirmed to The Moscow Times. A source close to USM said the deal was worth several tens of millions of dollars.

Meanwhile, media reports announced the sale of a minority stake in Gawker Media — a New York-based network of seven 'new media' websites including Gawker.com and Lifehacker — to Columbus Nova Technology Partners, the U.S. investment arm of oil and metal conglomerate Renova Group, owned by Viktor Vekselberg.

Then, an executive at Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, a startup working on a super high-speed futuristic train — the brainchild of Elon Musk — told The Moscow Times that the company was talking to a Russian private investor and the Russian government about building a line of the train in the country.

Hyperloop Technologies, a rival company also working on the project, said their executives would also be traveling to Moscow in early February.

News of the investments came after German Gref, the head of state-owned lender Sberbank, gave a speech in which he said Russia had fallen into a category of "downshifter" countries that had failed to adapt to economic and technological change.

Gref, a former economic development minister under President Vladimir Putin, said technology would be the driver of countries' success. He warned that without massive overhauls of state institutions and the education system, Russia would lag catastrophically behind more advanced rivals.

Yet the country's biggest tycoons are still turning to Silicon Valley, not Russia, to do business.

"Gref stated the obvious [in his speech.] Those guys [Usmanov and Vekselberg] also stated the obvious with their actions," Anton Nossik, a Russian Internet entrepreneur, told The Moscow Times.

The Most Money They Ever Made

The latest investments in Gawker and Uber are small in comparison to some of the massive deals of the not-so-distant past.

Yury Milner — a co-owner of Mail.ru and Russia's main social networks Odnoklassniki and VKontakte — paved the way for Russian investors in 2009, when he bought a 1.96 percent stake in Facebook for $200 million — considered a risky investment at the time.

Following Milner's aggressive investment strategy, Russian tycoons became known in Silicon Valley for paying huge sums for relatively small stakes in web titans. They also gained a reputation for wanted little in return in the form of board seats or other preferences.

Usmanov was one of the early backers of Milner's Digital Sky Technologies Fund, participating in further investments in Facebook and other tech frontrunners like Twitter, Spotify and Airbnb.

As the stocks rose, the men cashed in — "The most money they ever made, apart of course from privatizing state property, was made in Silicon Valley," Nossik said. Facebook's share value in the four years after Usmanov and Milner's first purchase rose ten-fold.

Political blessing came in 2010, when then-President Dmitry Medvedev visited Silicon Valley to meet with tech giants such as Google and tout Russia's own Skolkovo project — a nascent tech hub near Moscow overseen by Vekselberg.

But four years later the political tide turned. Western sanctions imposed on Russia for its annexation of Crimea in 2014 and involvement in Ukraine meant U.S. companies were no longer in vogue.

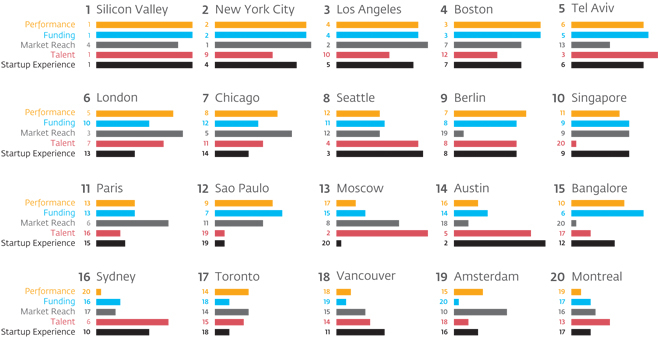

Ranking of startup ecosystems around the world

The change in political mood coincided with an announcement by Usmanov in March 2014 that he was divesting some of his U.S. assets, selling shares in Facebook and Apple to be redirected to Chinese companies such as Alibaba Group and JD.com, as well as to Russian assets. He sold, of course, at a profit.

Elena Martynova, deputy chief executive at USM, said in written comments that sanctions had not affected its strategy and that investments were made into companies regardless of their origins. "Our priority is not where they are based, but strong companies and technology," she said.

The new investments suggest that, through the political ups and downs, business has continued as usual.

Martynova echoed this. Usmanov's investments in Western companies have a "financial character," she said, while stakes in Russia were "strategic."

Thinking Big

Russia has little to offer Russia's richest tycoons, analysts said. Despite government attempts to foster an innovative culture, Russia's startup scene is neither as rich nor dynamic as its competitors.

The country's technology sector is dominated by a handful of large companies that offer a wide range of services, such as Yandex — the Russian equivalent of Google. One of the biggest, Mail.ru, is part-owned by Usmanov.

Startups in Moscow lack access to the capital and infrastructure available in the United States, and struggle to go global. And global is where the real money is made.

While Uber has grown in a few years to value some $50 billion last year, only a handful of Russian Internet firms and startups are worth more than $1 billion. Yandex, the biggest Russian company until it was overtaken last year by Mail.ru, now has a market capitalization of $4.2 billion.

For billionaires, that scale falls short. "[Usmanov] is a portfolio investor looking for a relatively minor share of capital. But on the other hand he wants to invest in something big. You don't have so much choice in Russia: Mail.ru, Yandex, and that is basically it," said Vladimir Korovkin, head of digital research at Skolkovo's Institute for Emerging Markets.

"It's more or less the same reason that Saudis are investing outside Saudi Arabia," he added.

State-Sponsored Innovation

The urge to invest in big, fast-growing stocks has only grown due to the economic slump in Russia. A sharp fall in the price of oil sucked investment out of the country, shrank the economy by 3.7 percent last year and collapsed the value of stocks.

Over January alone, Vekselberg's net worth fell by $450 million, and Usmanov's by a whopping $2 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

That makes the quick returns available in the United States more appealing, but it won't help Russian tech.

Russia is in a chicken-and-egg situation where the lack of investment is stalling development, and the lack of a tech scene makes Russian portfolio investors, and most of its innovative startups, look overseas, analysts said.

The falling stock markets have also harmed the biggest tech companies: Yandex's capitalization has fallen by two-thirds since its peak of $14.6 billion in early 2014.

The government has tried to jump-start the technology sector with Medvedev's launch of the Skolkovo innovation hub outside Moscow in 2010 and a clutch of state-backed investment funds. But in late January the cash-strapped government announced a shakeup that could see Skolkovo liquidated or absorbed into other structures.

Recently, Russia's ability to produce home-made technology is increasingly seen as a national security issue, leading to investments in state-owned search engines, software and mobile platforms that often aim to catch up to rather than exceed foreign technological achievements.

As a result, many Russian entrepreneurs are overly dependent on an infusion of state funds, and the economic crisis has not changed the status quo. "Many are more or less sitting and waiting for the good times to return. That's a very bad strategy," said Korovkin.

That may leave Russia in a bad place: In his speech, Sberbank's Gref warned that the new technology-driven world would see massive global wealth inequality, with the difference between leaders and losers "larger than during the industrial revolution."

Contact the authors at e.hartog@imedia.ru and p.hobson@imedia.ru. Follow the authors on Twitter: @EvaHartog, @peterhobson15

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.