The Russian economy is set to emerge from the coronavirus crisis on the same slow and steady trajectory it had settled on heading into it, economists believe.

The recent stabilization in the value of the ruble and relaxation of quarantine measures will be seen as “vindication” for Russia’s conservative economic model, analysts say — a mindset which makes future reform and diversification unlikely. Instead, Russia could see an even stronger government hand picking up the pieces after the sharpest shock to the economy in a generation.

‘Crooked V’

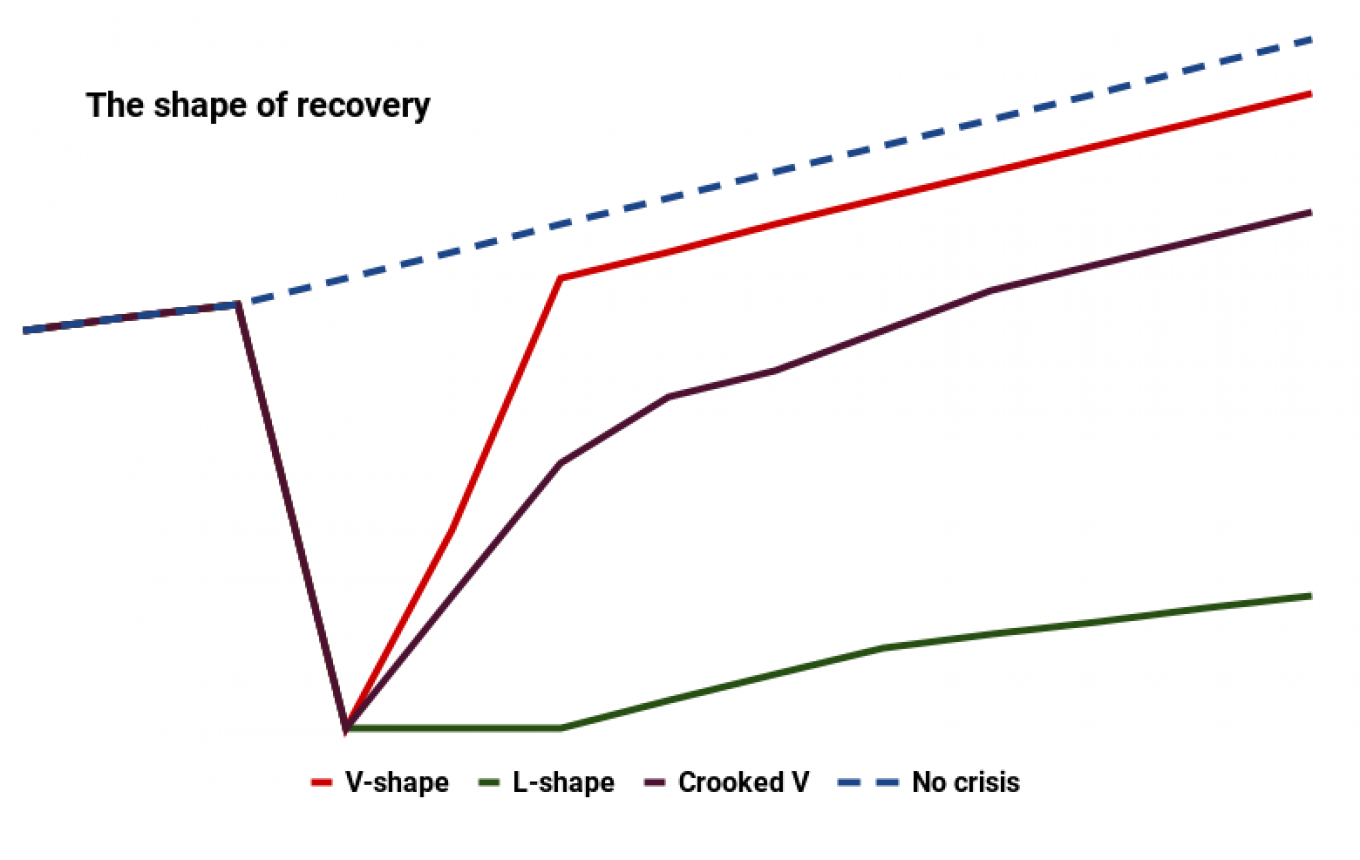

“The process of recovery will be gradual, definitely not V-shaped,” Alexander Morozov, head of research and forecasting at Russia’s Central Bank, said in a recent online discussion.

Russia has not grown faster than the global economy — a goal repeatedly stated by President Vlaidmir Putin — since 2012, and forecasts from international institutions show Russia falling further than the global average this year as well.

While an initial flurry of activity as Russia eases its quarantine measures is likely, Oleg Zamulin, director of macroeconomic research at Sberbank believes it will not be enough to recapture lost ground.

“Even if there is a bounceback once restrictions are lifted, the economy will recover only to a level substantially below normal for quite some time … followed by a long and tedious process to return to a normal level which will take several years,” he said.

Referring to the alphabet soup of possible recovery trajectories which economists have been debating since the outbreak of the pandemic, Zamulin said Russia’s could resemble a “crooked V.”

While Russia’s economy looks set to be smaller for a while longer, being in a position to even talk of a return to growth so soon after a fall in economic output and oil prices is a positive in the context of Russia’s modern economic history.

Instead of being forced to hike interest rates to counter a rapid devaluation in the ruble, as in 2014, Russia’s Central Bank has been able to play a role in stimulating the economy, first holding and then cutting interest rates. Later this month governor Elvira Nabiullina is set to shave off another full percentage point from Russia’s base rate, taking it to an all-time low of 4.5%.

The ruble is down only 10% since the start of the year, despite oil prices having fallen by more than a third and Russia having significantly cut back total oil production as part of a renewed OPEC+ deal brokered with Saudi Arabia. Russia’s overall international reserves — about a quarter of which sit in the rainy day National Welfare Fund — have even increased so far this year, Nordea Bank’s Tatiana Yevdokimova highlighted. They now stand at $566 billion, pushed higher by rising gold prices despite offloading to patch the hole in the government’s budget created by lower oil prices.

These successes will be seen as proof that Russia has adopted sound economic reforms and conservative policies since the 2014 crisis, Elina Ribakova, deputy chief economist at the Institute of International Finance told The Moscow Times.

“It’s important to give credit where credit is due: This conservative macroeconomic team — the Finance Ministry and the Central Bank — have performed spectacularly well.”

“It’s hard to think of a worse combined shock that could have triggered a proper financial or debt crisis — and we didn’t have that. Their position of fiscal prudence, the fiscal rule, inflation targeting and a flexible exchange rate is very important,” she added, pointing to the main reforms — seen as controversial in some quarters at the time — rolled out after the 2014 crisis.

Nevertheless, while Russian markets and the ruble have been calmed following spikes of global volatility in March, things are more mixed in the real economy.

The World Bank predicts Russia’s GDP will drop 6% this year, compared to a global average of 5.2%. Forecasts for Russia’s unofficial unemployment rate go as high as 20 million, and households could see their income fall by a fifth over the second quarter.

At the same time, figures on railway cargo, electricity consumption and industrial production point to a “less costly” Russian quarantine than that experienced in many other parts of the world, Sberbank’s Zamulin said.

This dichotomy — concerns over job losses and wage cuts, while industry and manufacturing beat expectations — has raised concerns that whatever shape it takes, Russia’s recovery will be uneven, potentially accentuating underlying weaknesses.

Monopolies winning

Analyzing official data on how different sectors of the Russian economy performed during April — the worst month of the economic downturn — Bill Tompson, head of the Eurasia division at the OECD said: “The sectors suffering the greatest contractions also have the largest shares of new and small firms. The potential impact on private sector development in an economy already dominated by large, often state-owned or controlled firms is devastating.”

This process — a winnowing out of Russia’s smaller service-oriented businesses — could also be aggravated by the policy response to the pandemic, which has focused support measures on the country’s largest firms, leaving smaller companies and entrepreneurs to largely fend for themselves.

Coming out of the initial crisis, “the dominant players — oligopolies and monopolies — will get even more of a competitive advantage over everybody else,” said Ribakova. “It’s a combination of natural advantage — when there’s a big shock … you have more buffers as a larger enterprise — and government support.”

“We have monopolies in almost every sector of the economy. And now, they’re only going to get stronger.”

The decision to focus relief on large state-affiliated companies — those either controlled directly by the government or by individuals close to the authorities — is just one trade-off the Kremlin has made in calibrating its economic response.

Another which will affect the pace of Russia’s recovery is the ending of quarantine measures, even as Russia records more than 8,000 new Covid-19 cases a day.

Without the luxury of a more diversified economy or a strong reserve currency, some of Russia’s macroeconomic options and stable borrowing costs are derived from its fiscal prudence. Drawing down reserves quickly could spook investors, trigger capital flight and push the ruble back into a position of being overly dependent on oil prices.

Therefore, what might look like deep pockets doesn’t play out in the same way for Russia as it would in developed economies. Russia “can’t deal with a prolonged shutdown, so is forced to take the human costs and reopen the economy … despite the rate of infections still being relatively high,” Ribakova said.

A possible second wave is on the agenda of those managing the economy. It is another reason the authorities say they need to be fiscally prudent now.

“As policymakers, we have to have something in our ammunition to be able to react if those risks materialize,” said Morozov.

In terms of a potential future wave of stimulus, supporting only large and loyal employers also makes sense from the Kremlin’s vantage point. With up to half of Russia’s workforce employed by the government or a state-controlled company, the government has easy channels through which it can dish out additional cash if it wants to get the economy moving faster, like pay rises and bonuses, rather than costly or complicated new social programs, furlough schemes or handouts.

“The state can say [to companies]: ‘Look, you have to support your employees and pay them benefits … You have to do your fiscal stimulus,’” Ribakova said.

Nevertheless, once Russia moves beyond the initial economic response to the crisis, the reliance on traditional industries and sources of employment could prove even more of a drag than before the coronavirus. A possibly permanent fall in global demand for oil, and a multibillion euro green energy push in the EU — Russia’s main export market — pose new, potentially devastating challenges to Russia’s key industry.

“It would be a mistake to treat the current drop in output as fully cyclical,” said Morozov. “The necessary structural changes that will take place in the world economy and in Russia will be pretty painful.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.