I hail from another Russia, one that came to be in August 1991. Over the next 25 years, my Russia would mutate into something entirely different. In truth, its undoing began at the very moment it was born. The man who gave it the first dose of lethal poison was Alexander Nevzorov, now a mildly obscure liberal critic of Vladimir Putin.

A star of combative perestroika-era television, Nevzorov initially exposed corruption, and indulged in showing gruesome footage from crime scenes. This was shocking for viewers, who had for decades been protected from such pictures.

But in 1991, Nevzorov found a new cause, lionizing OMON riot police in Riga who had conducted a dirty war against independence movements in Baltic countries. For several months, the Riga OMON terrorized Latvia. On the night between Jan. 19 and 20, they shot five people dead. On July 31, they executed seven people who manned a customs post at the border between neighboring Lithuania and Belarus.

For Russian and other Soviet democrats in 1991, the Riga OMON were despicable villains. Nevzorov looked the other way, producing instead a series of documentaries that pictured them as noble defenders of the collapsing empire, waging a desperate war against an overwhelming horde of pro-Western zombies. The films were collectively titled "Nashi."

‘Nashi’ is a pronoun best translated from Russian as "our guys," or literally — "ours". A piece of genius political branding, the term evokes scenes from Soviet war films, as well as fist and knife fights between teenagers from rival neighborhoods. It harks back to ancient mammalian pack instincts, and it reduces the complexity of the world to a simple black and white “us against them” picture.

The term also had the phonetical brilliance of hinting at the Nazis, a forbidden fruit that felt sweet to nationalist-leaning Russians of the perestroika era. But just as well, it also appealed to Bolshevik-inspired internationalists, because it didn’t necessarily presume discrimination on the basis of ethnicity. It didn't matter, for example, that the commander of Riga OMON Czeslaw Mlynnik was an ethnic Pole. What mattered is that he remained loyal to Moscow and stood firm in the face of what Nevzorov pictured as the coming Apocalypse.

Nashi films became the first manifestation of the emerging reactionary coalition, for which the democrats coined the term “red-browns,” thus reflecting its synthetic National-Bolshevik nature.

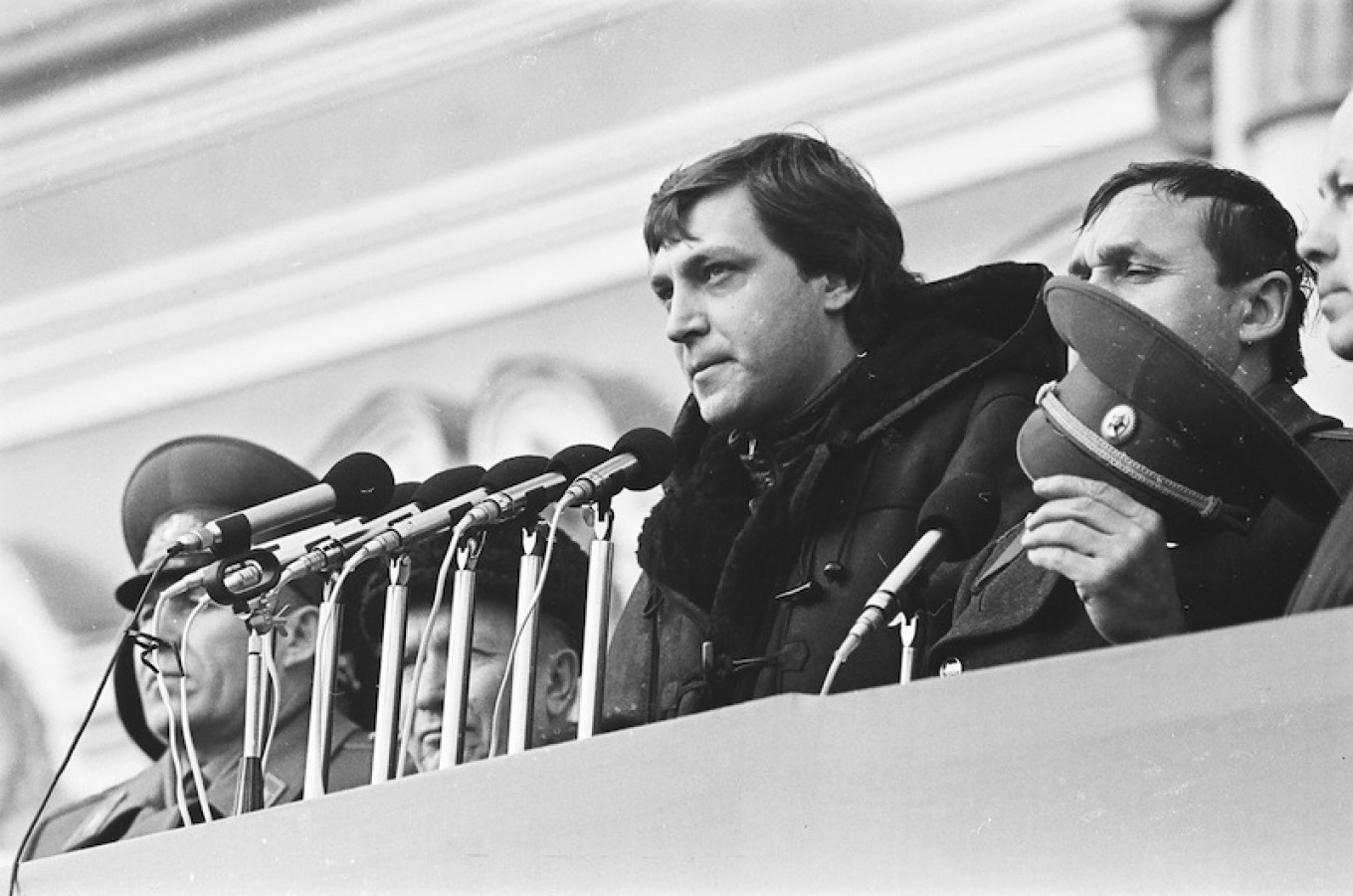

This was, however, a very different Russia. Things that seem unconceivable now were the broadly accepted norm back then. For example, the day after OMON’s attack on the Riga barricades, and a week after the massacre of pro-independence protesters by Soviet troops in Vilnius, at least half a million people rallied in the center of Moscow in support of Baltic independence.

It was one of the largest rallies in the history of Russia. It demonstrated how important the Baltic independence cause was for the Russian pro-democracy movement. That sentiment, which did not last long, was the reason why the Soviet Union collapsed peacefully 11 months later.

The red-browns were the underdogs of the time, unable to compete with the prevailing democrats. When the putschists were defeated in the Moscow August coup, Nevzorov created a political movement called Nashi. He was joined by Riga OMON commander Mlynnik, the latter’s political patron, Latvian politician Viktors Alksnis, and a motley crew of ultra-nationalists and neo-Communist politicians. Liberal journalists branded the group as "nashists," hinting at the fascist character of their ideology. Regardless, the project proved premature. With little take off in the fall of 1991, Nevzorov gradually lost interest in politics and started breeding horses.

But Nevzorov had pioneered a narrative which came to dominate the political discourse in Russia over the next two decades. In 1992, the red-browns made a major comeback, fueled by the disappointment with Yegor Gaidar’s “shock therapy” and real human tragedies caused by the poorly thought-out dissolution of the U.S.S.R. The red-brown rallies started drawing as many people as democratic ones just a few years ago. The Russian parliament, elected by the Soviet rules in 1990, drifted in that direction, too.

The climax came in the fall of 1993, when a broad red-brown coalition, including Mlynnik and Alksnis, came to the defense of the rebellious Russian parliament. The uprising was brutally squashed by troops loyal to president Boris Yeltsin. Nonetheless, two months later Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s LDPR, a force fueled by the same newly-created red-brown Nashist ideology, came first in a free parliamentary election. The developments famously prompted writer Yury Karyakin to shout live on television: “Russia, you’ve gone nuts!”.

The events of 1993 destroyed the democratic coalition that brought President Boris Yeltsin to power. Many democrats lamented the heavy-handed dissolution of the parliament, and sympathized with its defenders. Others became obsessed with the idea that Russia needed a dictator like the Chilean Augusto Pinochet to modernize efficiently. Their effort to identify and coach a suitable figure first resulted in the promotion of general Alexander Lebed, who was touted in the West as the "iron man” Russia really needed.

That first idea of a Russian Pinochet was eventually replaced with a more flexible and sophisticated one in the form of Vladimir Putin. Under Putin, the unwinding of 1991 Russia, hitherto a process carried out by stealth, proceeded in an increasingly open manner.

The Nashi brand was too good not be recycled by Putin's administration. So, in 2005, it returned via a youth movement that would not only share the name but the ideology of ultra-nationalism cum Soviet nostalgia. The Nashi of 2005, however, had a much slicker modern and forward-looking interface. The Nashists, as they were once again branded by the liberal press, were instrumental in marginalising the liberal discourse and forming a solid, “aggressively-obedient” — to use another term from 1991 — pro-Putin majority.

The eventual symbolic victory of "Nashism" over 1991 Russia came in the shape of "Krym nash," (Crimea's Ours) — a propaganda meme synonymous with the March 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea. This was when Putin finally broke the taboo on Russia resolving post-Soviet territorial disputes with the use of force. In 1991 this was something that prevented the Yugoslav scenario in the former U.S.S.R., thanks to a broad consensus that Russia shouldn't get dragged into a civil war.

At its conception, Nashism felt like a reactionary ideology that would be eventually swept away by the by the wind of history. Russia was lagging far behind the West in political development, so naturally it was more prone to backward ideas. But despite expectations, not only did Nashism linger on for two decades, it grew stronger. Today’s Nashism is young, creative and media-savvy. Worst of all, it has begun to spread far beyond Russian borders.

An endemic, yet instantly recognizable form of Nashism has engulfed Ukraine, fuelled by the ongoing conflict in the east. The patriotic fervour and rampant populism are gradually killing off meaningful discourse and critical thinking, marginalizing liberals and intellectuals. The visible longing for authoritarianism has resulted in the emergence of ex-prisoner Nadiya Savchenko at the top of popularity ratings. The conciliatory stance on the conflict, which she adopted, felt like a deja vu for someone who remembers General Lebed peace-making efforts in Chechnya, which resulted in 1996 Khasavyurt agreements, and brought an end to the First Chechen War.

Similarities between Ukraine and Russia might not be so surprising. What is unusual is the way the same breed of pack behavior, toxic populist rhetoric and intolerance of otherness is achieving political victories in hitherto impregnable fortresses of Western democracy. Looking at Trump, the Brexiteers or Marine Le Pen, someone who has lived through 1990s Russia can’t help but shout out “hey, guys we’ve already been here!”

This is the point when you begin to wonder whether is Russia really so backward after all. Or whether the contrary is true: Contemporary Russia is, in fact, a terrifying preview of the dark future awaiting the rest of the world.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.