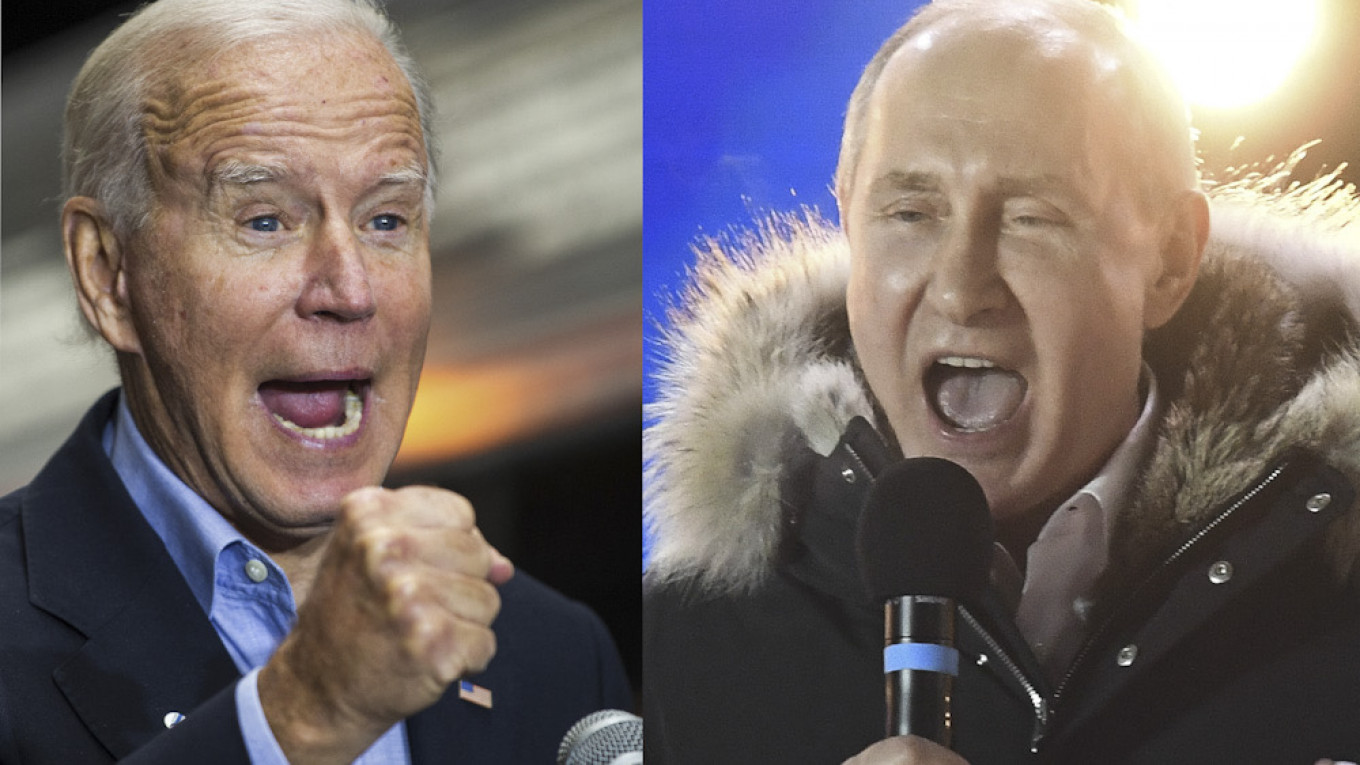

In the long and troubled history of U.S.-Russia relations, few summits have been as ill-conceived as the upcoming meeting between Presidents Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin in Geneva.

Both sides have already announced that they have very low expectations of the summit and that no breakthroughs are in sight. It begs the question: Why meet at all?

We are told it is important to maintain open channels of communication with the Kremlin, to stabilize the relationship — which is at its worst point in decades — and so untie Biden’s hands to deal with the far greater priority of China.

But the rationale is flawed. Instead of restraining Putin, the summit will only serve to embolden him and bolster his domestic standing. It comes as an unexpected gift to the Russian President, who — as even his fiercest critics will have to admit — has played his hand remarkably well.

History lessons

The Russian leadership craves nothing quite as much as international recognition. The regime cannot rely on domestic sources of legitimacy — only arrived at through free and fair elections, which Russia has not seen in a very long time — but can secure external recognition through the manner of its interaction with the West.

Soviet leaders delighted in summitry, which allowed them to stand tall and proud on an equal footing with U.S. presidents. They projected the message, to a domestic audience as well as Moscow’s allies, that their confrontational policies were paying off. The U.S. recognizes only strength, so ran the argument — they’ve recognized us, so doesn’t that show we are strong?

From the U.S. side, history shows summits have been a weak tool for attempting to influence policy in Moscow.

Nikita Khrushchev’s summit with Eisenhower in 1959 — coming as it did not long after the brutal Soviet crackdown in Hungary and just months after the infamous Berlin ultimatum — was an early example of exactly this kind of posturing.

Needless to say, it hardly led to a lasting improvement in Soviet-American relations, since the Soviets’ purpose was not actually to improve relations as much as it was to be legitimized by an American president.

Something similar happened in the June 1961 Vienna summit between John F. Kennedy and Khrushchev. Billed at the time as an effort to gauge each other’s intentions, while working towards strategic stability, the summit merely bolstered Khrushchev’s self-confidence. Just over a year later, the two superpowers found themselves in a precipitous nuclear stand-off over Cuba.

It took ten years before U.S. and Soviet leaders would meet again. Despite the hiatus, the pattern resumed.

In May 1972, instead of helping bring the Vietnamese to the negotiating table, Leonid Brezhnev used a meeting with Richard Nixon to harangue the American delegation over their “criminal” war in southeast Asia. He would later show transcripts of the meetings to Soviet allies.

Although Brezhnev genuinely desired a better relationship with Washington, the fabled détente did not actually temper his willingness to support revolutionary movements worldwide. What Brezhnev really wanted out of the summits was U.S. recognition of Soviet greatness — which was duly offered.

He continued to undercut the U.S. where he could and just months after a seemingly smooth 1973 summit in Washington, the Americans and the Soviets found themselves in a nuclear stand-off over a conflict in the Middle East.

The 1979 U.S.-Soviet summit in Vienna was soon followed by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

If Brezhnev was not willing to trade U.S. recognition for a more cooperative approach in the third world, then we should expect much less of Putin, who will also draw on his summit glory to improve Russia’s standing with its friends and clients like Iran, Syria, and North Korea. It is naïve to imagine that Putin will genuinely seek to find solutions to regional problems in a way that benefits the United States, as opposed to undermining it.

In contrast with Brezhnev, Putin has shown only very limited interest even in nuclear stability. If Moscow had a genuine interest in a new nuclear accord, then a summit would provide a wonderful opportunity to make headway. But no such agreement is in sight.

The China angle

Other arguments in favour of the Biden-Putin summit often include a curious strategic refrain that engagement with Russia will help Putin avoid falling into China’s arms, which would lessen the U.S.’ strategic difficulties as it seeks to deal with Beijing.

That argument overstates U.S. leverage in the Sino-Russian relationship, and ignores that an important foundation underpins the strong relationship between Moscow and Beijing: Political leaders in both countries understand that it is not in their interests to be played against each other by third parties.

In fact, the Chinese angle to the Biden-Putin summit works in precisely the opposite way that some U.S. strategists might believe, since Biden’s engagement with Putin actually raises the Russian leader’s stock with the Chinese, making it easier for Russia to pursue a close relationship with Beijing without paying a price for overreliance.

Another reason put forward for staging the summit is the importance of keeping channels of communication open.

What’s less clear is whether summitry is the only way that can be achieved. The telephone line is open, and Russian and U.S. officials meet and talk all the time. Putin also has frequent opportunities to air his imagined grievances in his own various statements and interviews.

What, then, can be said in the room that cannot otherwise be said over the phone?

After the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989, then-U.S. President George H.W. Bush refused to personally travel to Beijing, even as he attempted to restore relations, believing that meeting the Chinese in person would be seen as legitimizing the regime’s crackdown on the student protestors.

Why, then, is it acceptable to meet Putin, who has just unleashed an unprecedented crackdown on Russian civil society, arresting and imprisoning swathes of activists and opponents?

Does the summit not legitimize this crackdown? Does it not dishearten the Russian opposition, while emboldening Putin? The shifty Russian political elites — many of whom were beginning to harbor serious doubts about the wisdom of Putin’s foreign policy — will surely say: “Well, you know what, it wasn’t as disastrous as we thought.”

As his interview with NBC shows, Putin is already beginning to reap public dividends from the summit, before the two leaders have even met.

His talking points are being beamed back home to a domestic audience, endlessly recycled through the Russian propaganda machine to portray Putin as a wise statesman, triumphant over his enemies — both at home and abroad. The image cemented of a president recognized by the U.S. — indispensable, legitimate and secure.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.