In the Soviet Union, Western rock music was once so precious that at least one fan paid for it with his blood, said London musician Stephen Coates, who is in the middle of a project covering the unique phenomenon of music on “bones” or “ribs” — home-produced records on used X-ray film that were all the rage in the country before the advent of reel-to-reel tape records.

One of the project’s heroes, Rudolph Fuks, would donate his blood to earn money to get a record-making machine assembled for him by an acquaintance. Perhaps best-known as the producer of banned Soviet urban-folk singer Arkady Severny (1939-1980), Fuks was one of the leading figures in the era of X-ray records — producing and releasing Western music — jazz, rock and roll and boogie-woogie, which was frowned upon by the Soviet authorities.

“I think he told me that he went to hospital many times to pay somebody to make a recording machine, so in other words, in English you would say, ‘He gave his blood to make ‘bone,’” said Coates, speaking to The Moscow Times from London via Skype.

It is not known who came up first with the idea, but records on X-ray film appeared in the Soviet Union soon after World War II and were used for music that the heavily censored Soviet recording industry would not release.

Using homemade recording machines, the bootleggers of the era cut tracks on used X-ray film they bought from friendly medics and sold them illegally near record stores, or at unofficial trade spots in the city center.

Apart from artists like Elvis Presley and Little Richard, the plastic records — containing images of broken bones or ribs — featured banned émigré performers, tango and prison songs, Coates said.

In the first stage of his project, X-Ray Audio, Coates held a three-week exhibition at the London underground art venue The Horse Hospital earlier this year. It will be followed by a BBC radio documentary series and a book.

“The exhibition was some of the records that we’ve collected,” Coates said, “A Jubilee record player and various things, which explain the culture and also explain how to record onto plastic.”

“Aleks Kolkowski is an expert in early sound recording machines, so we did some live demonstrations where we made new ‘music-on-the ribs’ records,” he said.

The project also features a website, www.x-rayaudio.com, which contains some of the images, sounds and stories that Russian fans shared with Coates and allowed him to use.

“The idea is that we will make an archive of these X-rays records,” he said.

“I would like to hear from Russians who want to contribute. I would like this website to become the place for people — like a museum. I would really like to make this museum. We can build it.”

Coates first came across a 7” Soviet X-ray record when he came to Moscow to perform with his band, The Real Tuesday Weld, a few years ago.

“When I was in a flea market in Moscow, I saw something and I thought, ‘Is it a record or is it an X-ray?,’ so I bought it and asked our friends in Moscow, but they didn’t know about it, so I started to ask people and then I found out some small things and that’s how it started,” Coates said.

He said he found it resonant to his own music, which is influenced by pre-war records, Serge Gainsbourg, cabaret and retro electronica and was once described by Coates as “antique beat.”

“First of all, these things look very strange, quite ghost-like,” Coates said.

“There’s something about the aesthetics, which I connected with my music. I like to make music that feels a little ghost-like, actually, or connected with the past. So I saw something which reminded me of something in my own music.”

“In my music I like to try to create a sense of the past, mixed with the present, and some nostalgia mixed with the future, so something in these records felt like there was a connection.”

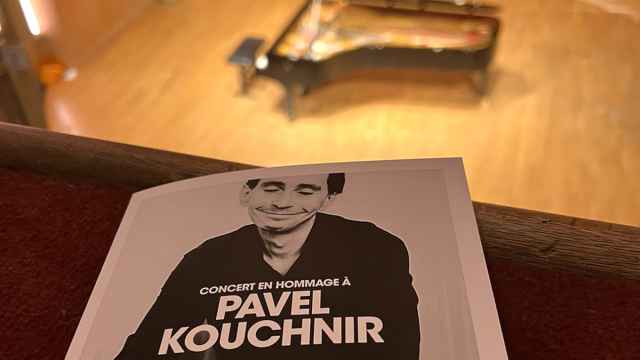

Coates in front of an X-ray record.

According to Coates, the records first appeared around 1947-1948 and were a popular medium for rock and roll and other banned music until 1963-1964, when reel-to-reel tape recorders became more broadly affordable in the Soviet Union. Records were still, however, available on the black market years later.

For people involved in the underground X-ray music industry it was only partly business, they also wanted to pass on forbidden music to the public, Coates said. Many paid for it with years in prison — Fuks did two years in jail.

“He told me, when he was arrested, they asked him to become an informer himself,” Coates said. “He said ‘yeah’ and he gave them wrong information, so then they got very angry with him and that’s when he went to prison. I like Rudi, he called himself a ‘culture trader.’”

Another of the project’s heroes is Nikolai Kurganov, who was into then banned “romance” singers, Russian tango and émigré music rather than rock and roll. He was physically threatened when he tried to sell some X-ray records in Moscow.

Kurganov and his cousin had made about 50 X-ray records and tried to sell them on the street. There, they were approached by a man who they thought was a potential buyer.

“He took them into a courtyard or a doorway and he pulled a knife out,” Coates said. “He put a knife against Nick’s ribs and he said, ‘You give me your ‘ribs,’ or you’re going to get this between your ribs!” (which, as I always say when I tell this story, just goes to show that Soviet criminals were quite poetic!). And Nick told me that he has never done anything illegal since.”

When he met Coates, Kurganov brought an old-fashioned portable gramophone, the kind you wind up by turning the handle, and put on a “bone” record.

“And it sounded terrible! I mean like really bad — you can just hear a little tune in the middle of the noise,” Coates said. “But Nick was smiling very happily, because I think this tune in the middle of the noise was a like a path, a road which let him back to his youth. But also I think it was a road that — when he was young — led him to a different world, actually. To a more romantic magical world, before the war.”

One of the things that drew Coates in was the immense effort of early Soviet rock fans’ to get the music they loved, however difficult and dangerous it was.

“That was really interesting to me — that people wanted to listen to the music they loved and they would make so much effort to do that, because it’s almost completely opposite to the time we live in now, because music is very, very easy to get,” he said.

“In fact, we have too much music. I feel like I got too much music. And it’s free (it might as well be free), you can share it, no problem! You can send people mp3s, you can send them Spotify playlists, you can send them a torrent with all music by The Beatles, and that means that in some way, music now has become worth less. It’s worth much less. I am not talking about the money. I am talking about emotion. It’s got less emotional weight. Music is becoming lighter — it weighs less all the time.

“I think what was beautiful about this story — it’s a story about music lovers who wanted to listen to and to share music.”

For Kolya Vasin, another hero of the project, one X-ray record became a life-changing experience. Vasin is an artist, best known as “Russia’s No. 1 Beatles fan,” who has been organizing tribute concerts on the birthdays of the Beatles since the early 1970s and turned his apartment into a Beatles museum.

Vasin, who published a book of memoirs under the title “Rock on Russian Bones” used to save his school lunch money to buy records.

“His first record on the bone was “Tutti Frutti,” which gave him an electric shock. And I think — I am not sure, but I think — he may have bought this record from Rudi,” Coates said.

“He would buy them from someone like Rudi in a square, but sometimes maybe even near the Melodiya official record shop on Nevsky [Prospekt, St. Petersburg’s main street] ... But he said you never were quite sure of what you had bought until you got home. You asked for rock and roll or for jazz, but you were never sure until you got home and played it.

“And sometimes you were disappointed. But sometimes you were very pleased. Because one day, of course, he bought a record on the bone, and when he got it home and played it on his mother’s 1958 Jubilee portable record player ... and he put a needle on the record and he heard: ‘Close your eyes and I kiss you, tomorrow I’ll miss you…,’ etc. And of course, as we know, his life was never the same again. He completely changed — he heard the sound of something from another world.”

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.