Using their hands to shade the screen from the sun, the officials and Greenpeace staff huddled around a laptop perched on the hood of a jeep.

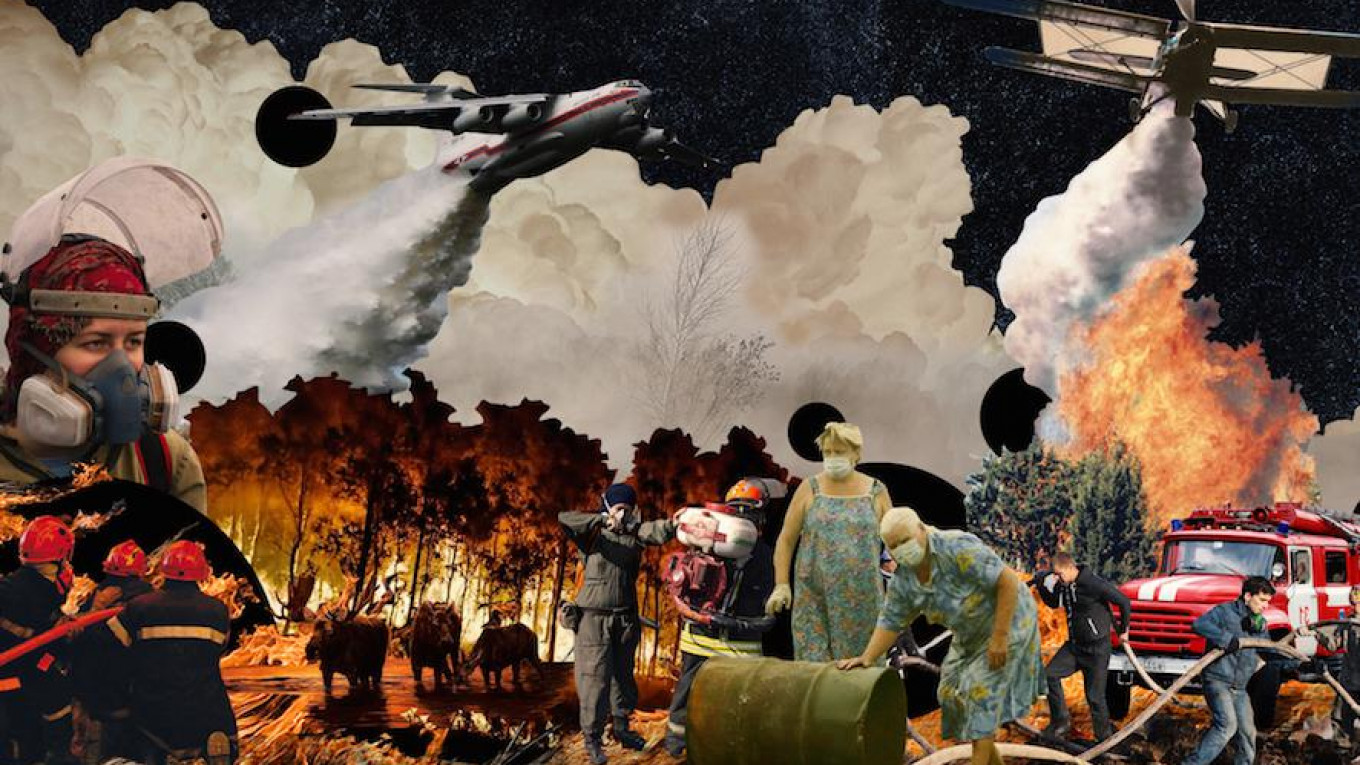

The biggest forest fire in the Moscow region this year had just ripped through the area. Firemen and forestry officials assumed they had almost put it out. But a volunteer firefighting brigade from international environmental organization Greenpeace thought otherwise.

The laptop played footage from a drone that Greenpeace had launched over the area they suspected peat was still burning in. A plume of smoke indicated they were probably right.

The officials agreed to walk with the Greenpeace team through a landscape of black ash and charred trees to check. The deputy head of the Moscow Region’s Emergency Situations Ministry, Aleksei Loginov, switched his smart dress shoes for boots.

On approaching the spot, acrid white smoke — the tell-tale sign of a peat fire — hung in the air. And, sure enough, two large sections of peat were smoldering on either side of a drainage canal.

“Without us, they would simply not have gone to look for it,” says Grigory Kuksin, an ex-fireman, and leader of the Greenpeace expedition.

Loginov says Greenpeace were “definitely” providing a useful service. Peat fires in the Moscow region were responsible for a thick smog in 2010 that caused hundreds of deaths and blanketed the Russian capital for weeks. They can extend deep below ground and burn for months, even years. And they are extremely difficult to extinguish.

This particular fire, if unattended, could have grown through the summer and set the forest alight again later in the year, says Kuksin.

“It’s always galling when you don’t finish the job and leave the peat [burning]. Tut, tut, tut!” he tells the group of half -a- dozen officials from the local administration, the Forest Fund and Emergency Situations Ministry.

Greenpeace organizes regular volunteer firefighting expeditions all over Russia: from Siberia to the delta of the Volga river near Astrakhan. There are about 30 volunteers from Moscow who regularly take part in firefighting trips. Other groups are based across the country. On this visit to the Moscow region last week, there were three volunteers and three Greenpeace staff.

The volunteers undergo a special training course during the winter months where they are taught the basics of firefighting, how to read maps and how to identify the sites of possible fires.

Dariya Gorchakova, a slight 29-year-old PR manager, first volunteered for Greenpeace when she was living in the southern Russian city of Astrakahan seven years ago. Gorchakova took part in expeditions to tackle the region’s large grass and reed fires. Unlike peat fires, which present a slow-burning danger, grass fires are “very frightening,” she says. “You can just be faced with a wall of flames.”

Gorchakova says that volunteer firefighters do not have to be physically strong and that they include a mix of women and men of different ages.

“I like the process of extinguishing fires,” she says. “People don’t understand that these fires, which you don’t see when you are in a town or city, are very dangerous.”

Officials don’t understand why volunteers put out fires for free. Volunteers usually do not believe officials are honest or do their job responsibly

Unlike in other countries where volunteer firefighters are usually given mundane tasks to do by professional firefighters, this is reversed in Russia. Greenpeace’s team often has more sophisticated equipment and more specialized knowledge than the firefighters they work with.

“We play the role of a highly-qualified specialist group which is a very unusual role for a civic organization,” says Kuksin. “We hope that one day firemen and forest workers will be more qualified than volunteers but for the moment we are trying to preserve this knowledge.”

Volunteer Darya Kalinina, 23, started going on firefighting trips with Greenpeace when she was a student at Moscow State University. At a second peat fire later in the day, she explained to Aleksei Kalinin, head of Lukhovitsky District Forest Fund, how to use a large thermometer to check earth temperatures.

Kalinina directed local firefighters to dozens of small peat fires so they could be extinguished — telling them several times to return to blazes that were still burning despite having water poured on them.

Lukhovitsky District, about 80 miles from Moscow, has large areas of peat, which was extracted as fuel from the 19th century until the industry collapsed in the 1980s. It was one of the centers of the catastrophic 2010 fires: burnt-out villages and charred remains of forests are still visible.

In central Russia, early spring — when there is no green grass — is a period of high risk for forest fires. The conflagrations are often started by holidaymakers or people who burn dry grass in a practice condemned by experts as harmful for the land and extremely dangerous.

Cooperation between Greenpeace and local authorities has dramatically improved over the seven years since the 2010 blazes, Kuksin says, but officials are still often “more scared of their bosses than society” and some under-report the size of fires because they fear they will be punished if a fire is judged to have grown out of control.

“Local officials don’t understand why volunteers put out fires for free. Volunteers usually do not believe an official can be honest and do their job responsibly: we are working to overcome this barrier,” says Kuksin.

In the evening, before returning to Moscow, the Greenpeace team returned to the site of the first peat fire to see how effectively it was being extinguished. A bulldozer, wreathed in white smoke, was pushing the smoldering peat into the canal while firefighters sprayed water on the earth to ensure the bulldozer didn’t overheat.

A second bulldozer is on its way, says Kalinin. “We’ll finish in a few hours.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.