Kazakh authorities this month arrested anti-war activist and musician Ayhal Ammosov, a Russian national hailing from the Far East republic of Sakha (Yakutia).

Though Ammosov’s name might be known to few abroad and elsewhere in Russia, he is something of a local celebrity in his native Sakha, first rising to prominence as an eccentric punk frontman and later becoming one of the region’s most noticeable critics of the invasion of Ukraine.

Ammosov — whose legal name is Igor Ivanov — fled Sakha for Kazakhstan at the end of last year after authorities opened a criminal investigation against him on suspicion of spreading “fake news” about the Russian army.

Despite his physical absence from the country, he continued to face pressure from the Russian authorities.

In February, a new criminal case accusing Ammosov of “incitement to commit acts of terrorism” was opened in his home city of Yakutsk, according to his lawyer, Murat Adam. Soon after, the musician was added to Russia’s “terrorists and extremists” register and authorities issued a warrant for his arrest.

Adam told The Moscow Times that this happened because Ammosov had written on social media that Russian citizens could give him a gift by setting military enlistment offices on fire “to show their protest against all war actions committed by Russia against Ukraine.”

A local court in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, ordered Ammasov to 40 days of arrest on Oct. 9 in connection with a Russian extradition request. His time in detention is likely to be extended and a subsequent deportation to Russia can’t be ruled out, his lawyer said.

If deported, the 31-year-old activist could face up to seven years in prison.

A poet and a songwriter, Ammosov was well-known among Sakha’s progressive-minded youth long before the start of the Ukraine war. Even then, his views could be deemed too radical for the taste of Russian officials.

As the frontman of punk band Crispy Newspaper, Ammosov’s lyrics spoke of indigenous rights, environmental issues and corruption and didn’t shy away from criticizing Yakutian business giant Alrosa, the world’s largest diamond mining company. Most of his songs were written in the indigenous Sakha language.

“Already then he was spreading awareness about social issues among young people,” said Sargylana Kondakova, co-founder of the Free Yakutia Foundation, the region’s largest anti-war movement.

In a rare interview with the independent news outlet Holod published in February, Ammosov said he had harbored an interest in politics from an early age. He explained that his pseudonym is an homage to indigenous Sakha traditions and the Yakut revolutionary Maxim Ammosov, one of the founding fathers of the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, who was killed in Stalin’s Great Purge.

Ammosov’s anti-war activism, in turn, was an automatic reaction to Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

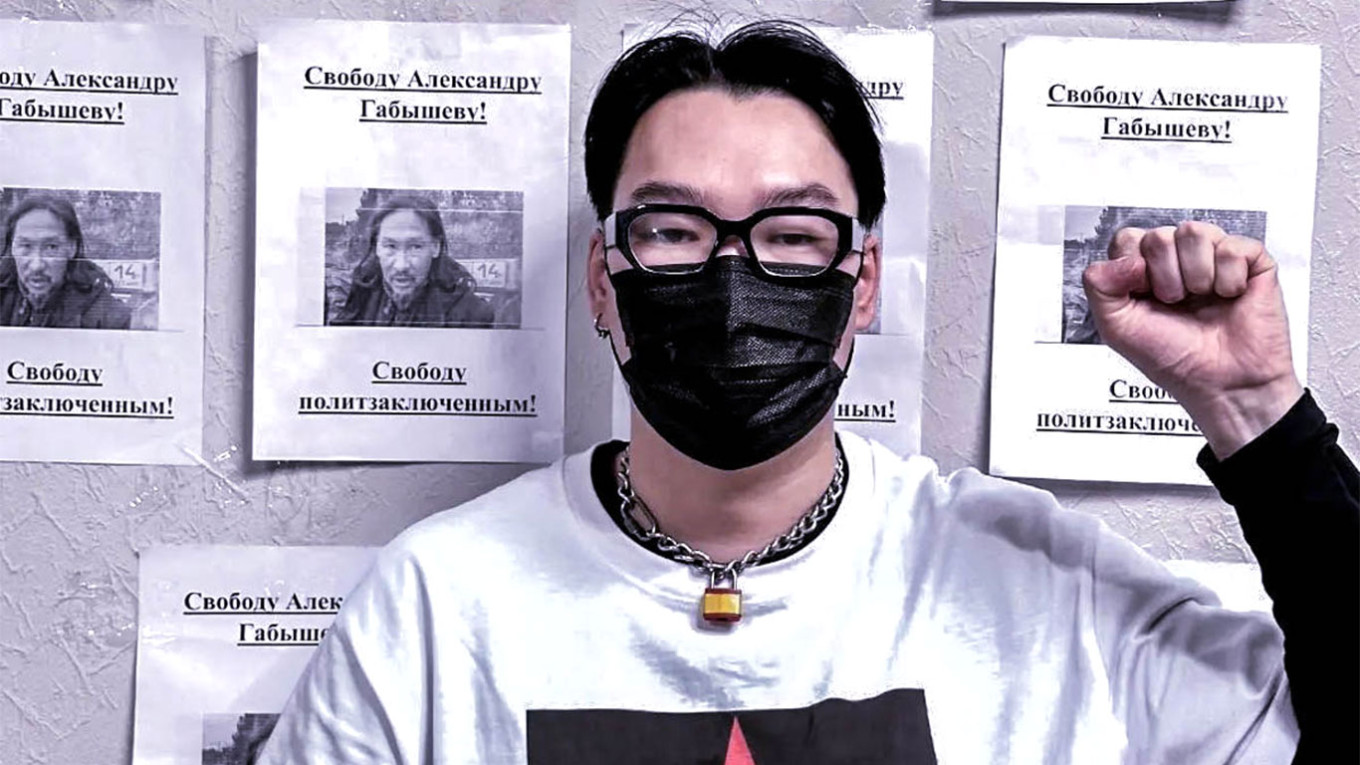

In addition to distributing anti-war leaflets and stickers in Sakha’s capital, Yakutsk, Ammosov staged a number of one-person pickets in the first few months of the war.

One of his most viral stunts was a picket in front of a funeral services office where he held up a picture of a coffin captioned “The groom has arrived” — a reference to the film “Cargo 200” — to highlight the steep death toll among Russian servicemen in Ukraine.

Local security forces soon opened a slew of administrative cases against Ammosov, accusing him of “discrediting” the Russian Armed Forces and of committing acts of hooliganism. Ammosov was found guilty in all instances and required to pay more than 90,000 rubles ($900) in fines. The Free Yakutia Foundation held a fundraiser to cover his legal costs.

“People from all over the republic, Russia, and from abroad sent money to help him. … We gathered the funds very quickly,” Kondakova of Free Yakutia told The Moscow Times.

Ammosov’s first criminal case came after an August 2022 protest where, ahead of a planned visit by Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin to Yakutsk, he hung a banner reading “Yakutian punk against war” on the facade of an indoor swimming pool in the city center.

Ammosov and a friend who filmed the performance were arrested on the spot. The musician then spent over a month in detention before being released to await trial.

“There was a feeling that the authorities themselves were scared of this case,” Kondakova explained.

“It was the first high-profile case in the republic and, on one hand, they wanted to make an example of it to silence others. On the other hand, they were scared that if Ayhal gets real jail time, it will prompt unrest.”

Ammosov’s trial was repeatedly postponed, and in December he disappeared from the public eye completely, resurfacing a while later in neighboring Kazakhstan.

“He had a difficult life here in Kazakhstan. … I know he constantly needed money,” Kazakhstan-based Buryat journalist Yevgeniya Baltatarova told The Moscow Times.

“Finding ways to express himself was important for Ayhal. He continued to engage in public activism here even though we [other exiles] advised him against that,” she said.

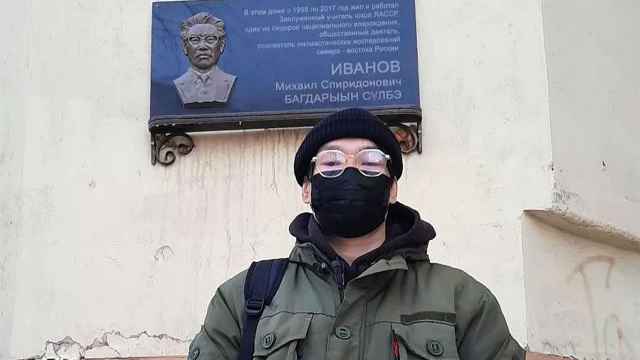

Ammosov continued to distribute anti-war flyers and stickers in Kazakhstan’s capital, Astana, and in Almaty. One depicted the Yakutian and Kazakh flags with the caption “Our nations are against Russian imperialism.”

In February 2023, Ammosov and a group of friends staged an unsanctioned rally near the Russian Embassy in Astana to mark the one-year anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine. The group was rounded up by security forces and taken in for questioning before they could make it to their protest location, according to Baltatarova. This was Ammosov’s first encounter with Kazakh law enforcement.

Now, Ammosov is in an isolated detention center in Almaty, where he awaits possible deportation back to Sakha. One of his few lifelines to the outside world are care packages and letters brought to the facility by Bota Sharipzhan, an activist with Oyan, Qazaqstan!, one of Kazakhstan’s leading civil rights movements.

Sharipzhan, who has long supported Kazakhstan’s political prisoners with care packages, decided to do the same for Ammosov and another detained Russian activist, Natalya Narskaya, fearing the two might be forgotten by fellow activists in both Kazakhstan and Russia.

“To be honest, I didn’t expect so much hype around it, but activists from Sakha immediately contacted me and offered to send money for the packages [for Ammosov],” Sharipzhan told The Moscow Times.

“I must be frank, I feel most sorry for Aykhal because he is Sakha and a lot of boys from [Russia’s] Asian republics go to die in the war,” she added. “In my opinion, he shouldn’t spend even a single day in prison for not wanting to die in a pointless war.”

But back home in his native Sakha, few seem to be talking about the arrest and possible deportation of a national punk hero.

“Last year everything was fresh, everything happened for the first time. … People had a very proactive and empathic response [to arrests],” said Free Yakutia’s Kondakova.

“But with new repressive laws, when each comment left on social media can land you a new fine … people became far less active politically.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.