The pressure of Western sanctions saw Russia scramble to maintain its market power as a key energy exporter, as well as preserve the supply of technologies necessary for its military and civilian sectors.

Domestically, this has meant Russia's increasing state control over the economy, coupled with a tolerance of "grey" schemes to evade sanctions and hide profits.

Internationally, this has pushed Russia, like Iran and Venezuela before it, to operate in an increasingly opaque economic environment relying on an increasingly complex web of interlocutors.

Tracking Russia’s oil exports

Russia’s energy trade is but one glaring example.

Before the Ukraine war, Russia sold a significant proportion — about 60% — of its seaborne oil to Europe. Accordingly, the market price of the Urals blend, as assessed by Western agencies such as Argus and cited by officials, served as a credible benchmark for Russian oil sold worldwide.

Things changed in the wake of the Western restrictions, when Russia's seaborne oil was diverted to China and India using the so-called "shadow fleet," ships that do not use Western services and are therefore not subject to restrictions such as the $60 price cap.

As of spring 2024, nearly 77% of Russian oil exports were carried by tankers that were not flagged, owned or operated by companies in the G7, EU, Australia, Switzerland and Norway, and were not insured by Western protection, the S&P data showed.

As the Argus methodology lost relevance because it was tied to European sales, analysts used their own market sources and customs statistics for countries such as India, a major consumer of Russian seaborne oil, to infer that the real prices of Russian oil were higher than those reported.

For example, in early 2023, energy analyst Sergei Vakulenko estimated the market prices at which Russia sold its oil at around $75, as opposed to the $47 benchmark price cited by Russian officials and Argus.

Since then, analysts have revised their methodology to reflect these trends and incorporated information on Russian sales to China into their estimates, but there is still no single benchmark that tells us the “correct” story of the pricing of Russian oil exports, says Marco Siddi, a leading researcher with the Finnish Institute of International Affairs.

This complicates the analysis of the impact of restrictions on Russian energy and makes it difficult to fine-tune restrictions on the country, Siddi added.

Tracking Russia’s oil trade is certainly a much harder task, but analysts are adapting to this new environment, Ben McWilliams, a Bruegel Affiliate fellow, agrees.

For example, the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), a think tank, uses satellite tracking to determine the volume of Russian oil transported, while customs data from importing countries such as India may serve as a "reasonable" indicator of what's happening to Russian prices, McWilliams noted.

The Kremlin’s slush funds

Then there is the question of where Moscow keeps the money it pockets from the energy trade, its biggest source of revenue.

Here, too, there is little transparency, and there are suspicions that the growing amount of money never actually returns to Russia, but sits in the accounts of the middlemen who facilitate the shipments or in other Russian-linked accounts.

In one interview, Segei Vakulenko described the general chain of events of how money from the oil trade may possibly end up in the accounts of offshore companies.

A Russian company sells oil at a relatively low price to a company registered in, say, Fujairah in the UAE, and that company in turn sells the same batch of oil at a higher price to an Indian or Chinese refiner.

Part of the money difference goes into the intermediary's account in Hong Kong or the UAE and is then used to buy sanctioned goods for Russia, Vakulenko explained.

As a result, the lack of transparency in oil pricing allows Russian-linked companies to inflate transport costs in order to circumvent the $60 oil price cap and siphon off money.

There is no precise estimate of how much money Russian companies might have stashed outside the country.

In its July 2023 report, the Peterson Institute (PIIE) think tank estimated that Russian banks and companies acquired $147 billion in new assets abroad in 2022 alone, with little known about their physical locations or the currencies of the transactions.

The flow of Russian assets abroad continues, as the flow of the country’s financial assets abroad rose by $44.6 billion in the first seven months of 2024, up from $21.4 billion, Russia’s Central Bank said.

Bloomberg cited the delayed repatriation of funds to Russia from foreign partners amid the threat of secondary sanctions as a reason for the increase in Russia's foreign financial assets. In other words, not all the funds that Russia and its companies have abroad can be used as Moscow sees fit.

There is no clarity on how much money the Kremlin has stashed away under the control of Russian and foreign companies, but the sum of liquid funds it can easily tap into is likely to be in the range of a few tens of billions, not hundreds, said Maximillian Hess, the founder of Enmetena Advisory and a Foreign Policy Research Institute fellow.

Russia’s murky trade

This brings up another issue related to Russia's “dodgy” accounting: its trade statistics, which Moscow has almost completely stopped publishing since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Instead, analysts have to rely on data from Russia's trading partners, leaks of Russian classified data, and commercial data providers such as ImportGenuis to arrive at credible estimates.

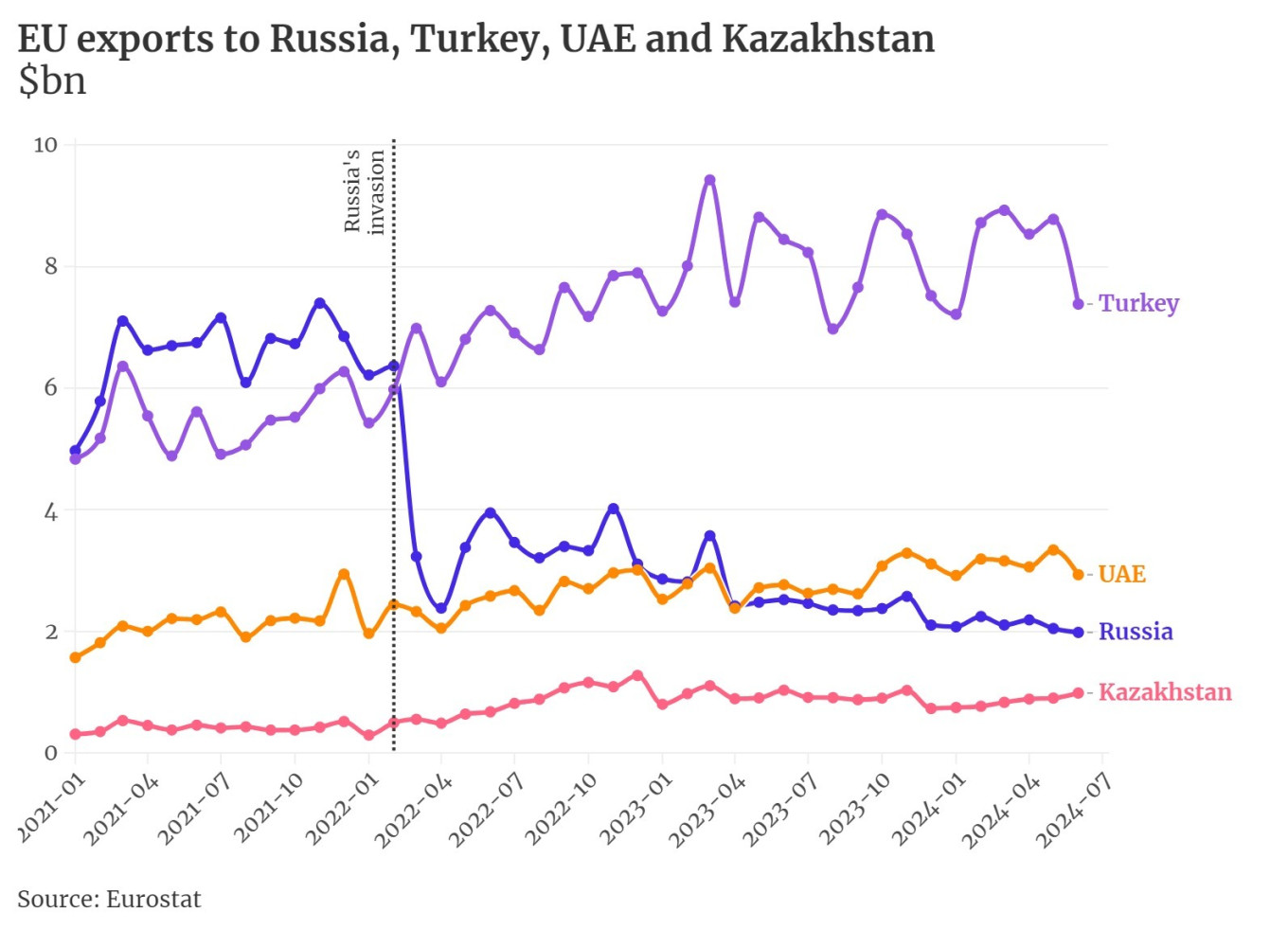

On the surface, EU trade with Russia plummeted after the Kremlin's invasion of Ukraine, reaching a post-Cold War nadir.

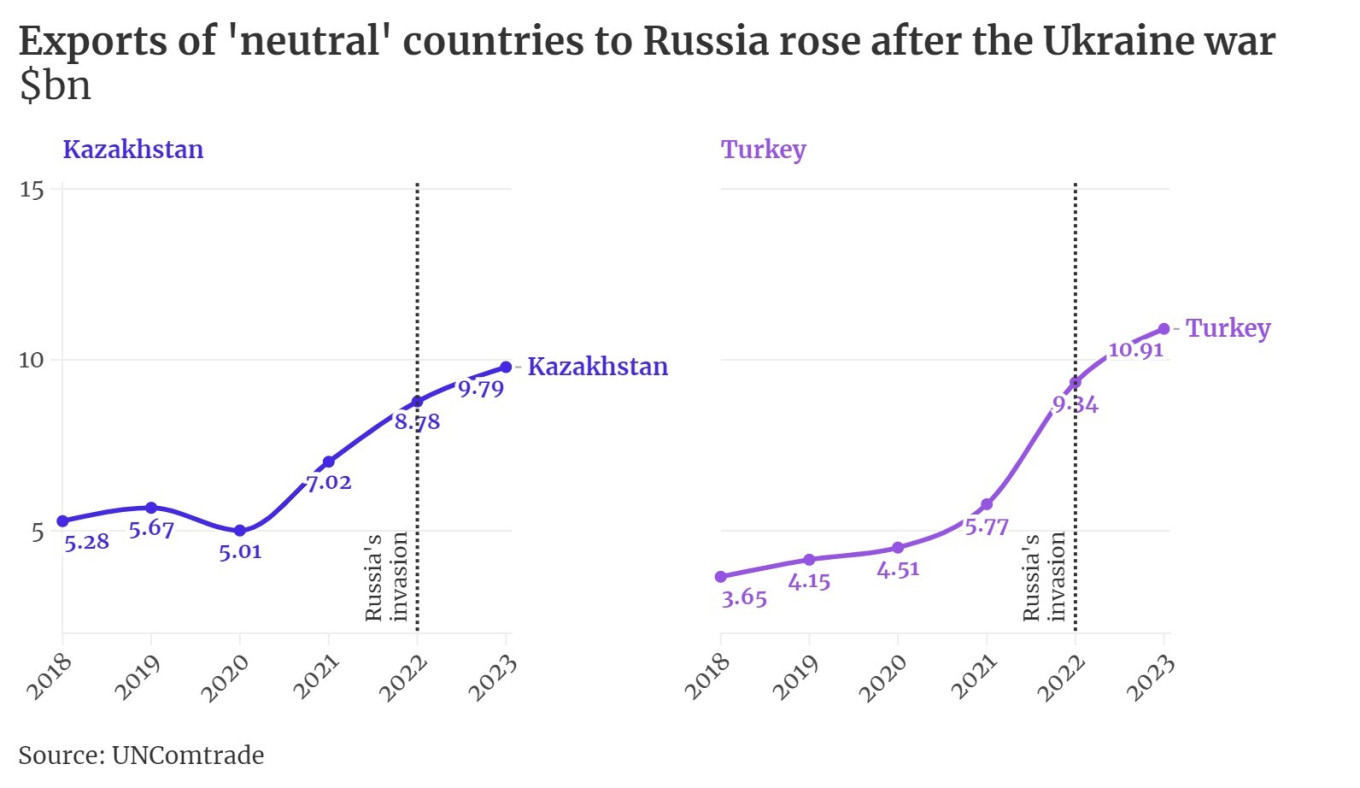

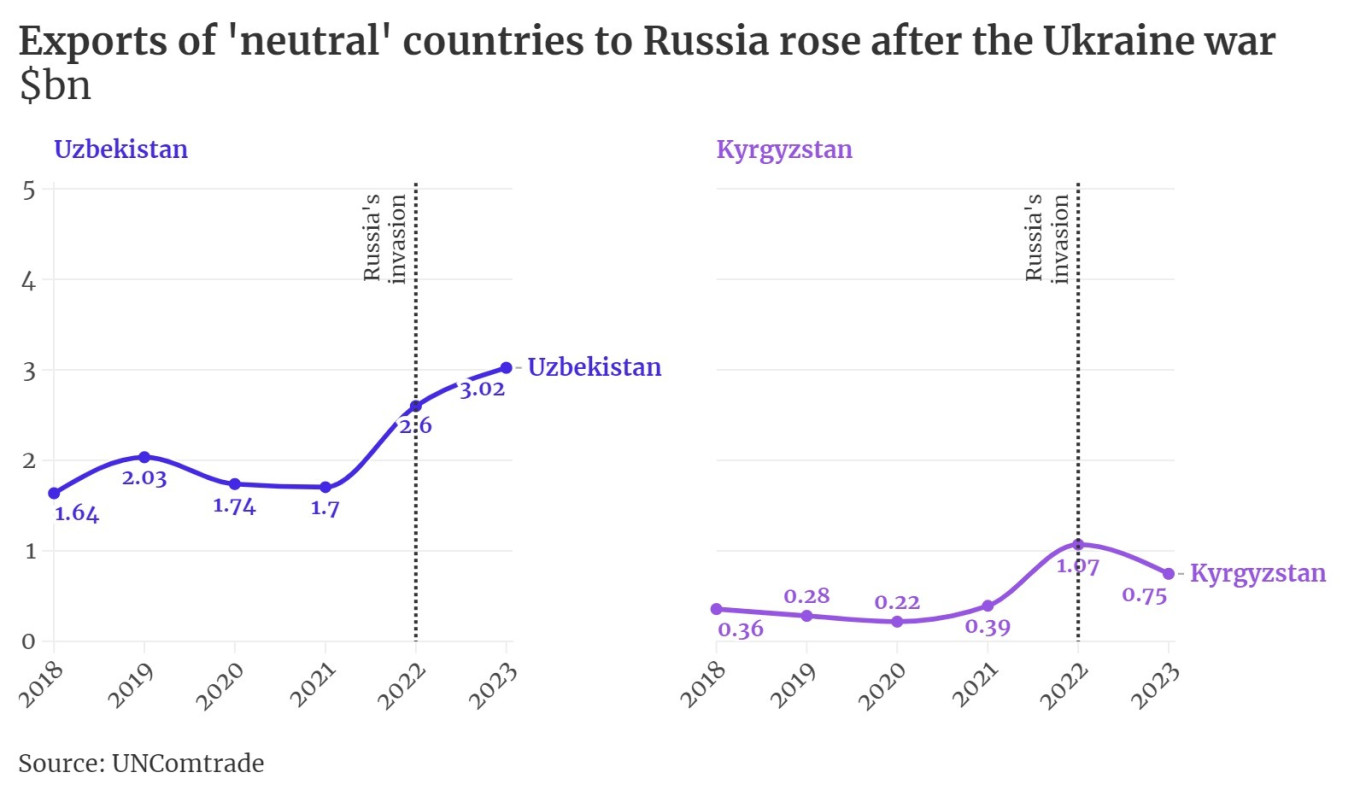

And yet, Moscow remains dependent on Western goods. It's just that these goods don't go directly to Russia, but are shipped through intermediary countries such as Turkey, UAE, China and Russian neighbors not sanctioned by the West.

A notable example is the car trade.

According to Bloomberg analyst Gerard DiPippo, when transshipments are taken into account, exports of combustion-engine cars to Russia from the EU's top five producers — the Czech Republic, Germany, France, Slovakia and Spain — are almost back to pre-war levels.

DiPippo cited Belarus as the largest route of transshipments, followed by Kyrgyzstan, Georgia and Kazakhstan.

Russia also imported more than $1 billion worth of advanced chips from the U.S. and Europe in 2023 that can be used to power Moscow’s war machine, despite the restrictions, Bloomberg reported, citing confidential customs data.

The list of chipmakers included U.S.-based Intel Corp, Advanced Micro Devices and Analog Devices Inc, as well as European brands such as Infineon Technologies AG.

The companies themselves are not accused of breaking any laws, while the confidential Russian data doesn't show who exported the technologies to the country.

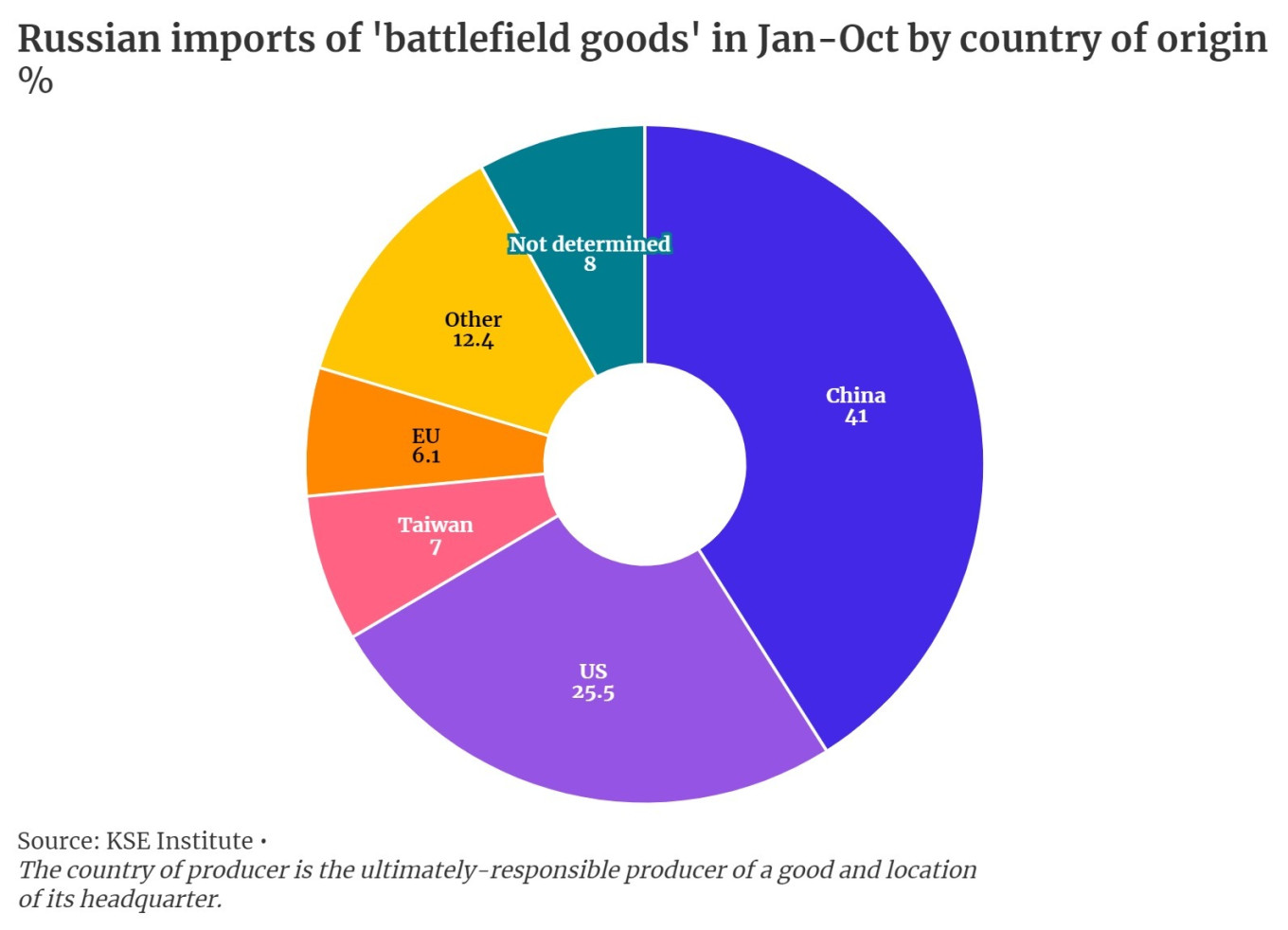

Research by the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) shows that Russia continues to rely on Western technology to power its war machine, even if the scale of imports has slightly decelerated.

Russia imported $8.77 billion worth of goods needed for its military in the first 10 months of 2023, only 10% less than it imported before sanctions were imposed, according to a January 2024 report. Telecommunications equipment and semiconductors accounted for about half of these goods.

Companies headquartered in coalition countries were responsible for at least 43.9% of the imports of the so-called “battlefield goods” it needs to wage its war on Ukraine, KSE said.

Some of Russia’s sanctions-busting schemes are relatively straightforward.

A Russian company can open a legal entity in a neighboring country, such as Kyrgyzstan or Kazakhstan, and use it to buy Western goods and then import them directly into Russia or via Belarus. This method works well for goods that are not of high priority for military use, such as luxury clothing or textile and woodworking machinery.

There are also more sophisticated methods reserved for more sensitive items such as chips or machine tools used to produce missile components.

The Wall Street Journal, for example, told the story of Russian company Convex, which imported equipment for the country's counterintelligence service through the website Nag. The platform used a network of suppliers in China to evade sanctions.

The newspaper also documented the use of Moroccan ports to ship electronics Moscow needs.

Rise of the middlemen

In the increasingly opaque world of Russian trade, the middlemen who stand between buyer and seller are becoming increasingly important.

Just as the Kremlin increasingly relies on intermediaries for its illicit trade, journalists, officials and analysts have exposed Russian sanctions-busting schemes using the analysis of existing data, as well as their own sources among market participants and even customs officials.

With no end in sight to the Russia-Ukraine war, experts have called for Western officials to strengthen their ability to shine a spotlight on the shadowy side of the global economy.

Energy analyst Ben McWilliams called for the creation of a “G7 task force” to maintain and improve data on Russian oil exports and make it available to the public.

FIIA's Marco Siddi, too, argued that Western government agencies would have to do more "complex work" if they want to tighten energy restrictions on Russia, and it is unclear whether they would achieve their goals anyway as Moscow has so far shown resilience to oil sanctions in particular.

Similarly, the KSE report called for the creation of an electronic tracking system for sanctioned goods and the strengthening of export control agencies to better detect export violations.

At any rate, there is a silver lining to this cat-and-mouse game of sanctions-busting: Western investment in trade monitoring is likely to be more effective than the fees the Russians pay to their interlocutors.

While it is impossible to cut Russia off completely from global trade, it is possible to ensure that for every dollar the West spends on improving sanctions monitoring, Russia loses ten by bleeding more and more of its money to various interlocutors and shadow logistics schemes.

“The question of introducing sanctions on Russian oil is a billion or trillion dollar one and maintaining the database on Russian oil exports might cost $10 million,” McWilliams said.

A combination of Western companies tightening control over their production and distribution chains and strengthening the work of Western agencies should put enough pressure on Russia over time to make a difference, analyst Hess said.

He noted that equipment such as chips or CNC machines made in countries outside the West, such as South Korea, should be subject to stricter controls to make it harder for the Russians to get their hands on technical gear.

"Some say we don't need sanctions at all, that they're useless just because the Russian economy hasn't ground to a halt, but this is a complex and grinding process. We are already seeing banks around the world, including Russia's neighbors, tightening their compliance, while the production rate of Russian military equipment is slowing down," Hess added, stressing that the “world is better off with Putin having to face these costs rather than the alternative of easing sanctions.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.