Svetlana Alexievich, the Belorussian author who just won the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature, might be the greatest writer people don't want to read.

Russians may be pleased that for the first time in almost 30 years — and for only the fifth time in history — an author who writes in Russian has won the highest literary award in the world. But that doesn't mean they're all eager to read Alexievich's works.

That is not to say that Alexievich is not well-known in Russia. She is the author of five books, three plays and over 20 screenplays for documentary films. She is the laureate of eight major foreign and six Russian awards, including the Leninsky Komsomol Prize in 1986 for her first book, "The War's Unwomanly Face," about the experiences of women in the Great Patriotic War. Although it was originally censured for its grim and less than heroic stories about the war, it was more highly regarded when glasnost became state policy under Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. By the end of the 1980s, almost 2 million copies of the book had been printed.

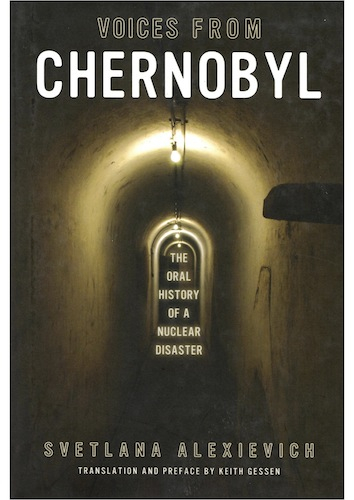

That book, like her later books, was written in a style that blurs the boundary between fiction and non-fiction. John O'Brien, director of the U.S. office of Dalkey Archive Press, the publisher of Alexievich's book "Voices From Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster," described her style in an email to The Moscow Times, "Fiction? Non-fiction? Let's say that she writes non-fiction while taking advantage of the devices available to a fiction writer."

Alexievich interviews people, transcribes their interviews, and then arranges and rearranges passages to form prose that reads more like a short story or novel than a documentary account. "Because of her method of interviewing people, then editing, then getting approval from the people she has interviewed, Svetlana adopts a very colloquial style that makes her work quite accessible," O'Brien said. "Her method is to make these non-fiction pieces into what might almost pass as short stories, while still remaining completely faithful to the facts and tone of the people being interviewed."

Voices from Chernobyl was first published in Russian in 1997. The English translation was awarded the 2005 National Book Critics Circle Award for general non-fiction.

Although the stories may be more accessible than a traditional non-fiction history, they are not easy reading. As journalist Alexander Minkin wrote in his blog, "They are really difficult books. They are hard to read. It's like taking care of someone who is extremely ill — duty makes you do it, but there is no pleasure in it."

Natasha Perova, publisher of GLAS New Russian Writing, who published excerpts of a book about love that Alexievich is still writing, told The Moscow Times that her first book "was an eye-opener; it was shattering and heart-rending. Her books are certainly not to be missed by thinking, honest people, although reading them is a traumatic experience. She did, indeed, create a monument to human suffering and courage."

Alexievich's other books are also about what Perova calls the "ulcers of Soviet society": "The Last Witnesses," tales of WWII told by people who were children during the war; "Boys in Zinc" about the Soviet-Afghan war; "Enchanted with Death," about people who committed suicide rather than live in the post-Soviet world; and "Second-Hand Time" about living through the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Her book about the aftermath of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, translated by Keith Gessen, is her best-known work in the English-speaking world and won the National Book Critics Circle Award in the U.S.

Alexievich's subject matter and criticism of the current Russian leadership and policies, particularly the annexation of Crimea, have kept official response to the Nobel prize muted. But the Russian literary world is delighted. Dmitry Bykov, Russia's most prolific writer and literary critic, told the radio station Ekho Moskvy that Alexievich's work represented the "Russian World — only not that Russian World that is trumpeted on television. Not the world of aggression, lies and chauvinism, but the world of the struggle for truth, the world that is kind and humane, the world of humanity."

He said that Alexievich's "fictional non-fiction" is part of a Belorussian literary tradition described by writer Ales Adamovich as "polyphony, a powerful tragic choir of various voices, where the author almost takes himself out of the book." Bykov said that Adamovich considered it blasphemous to write fiction about the horrors of the 20th century. "It's wrong to make things up. You have to tell the truth, the way it is. You must completely remove your own voice and let others tell the story. In that sense, Alexievich's contribution is very great indeed."

A sample of Svetlana Alexievich's writing can be found here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.