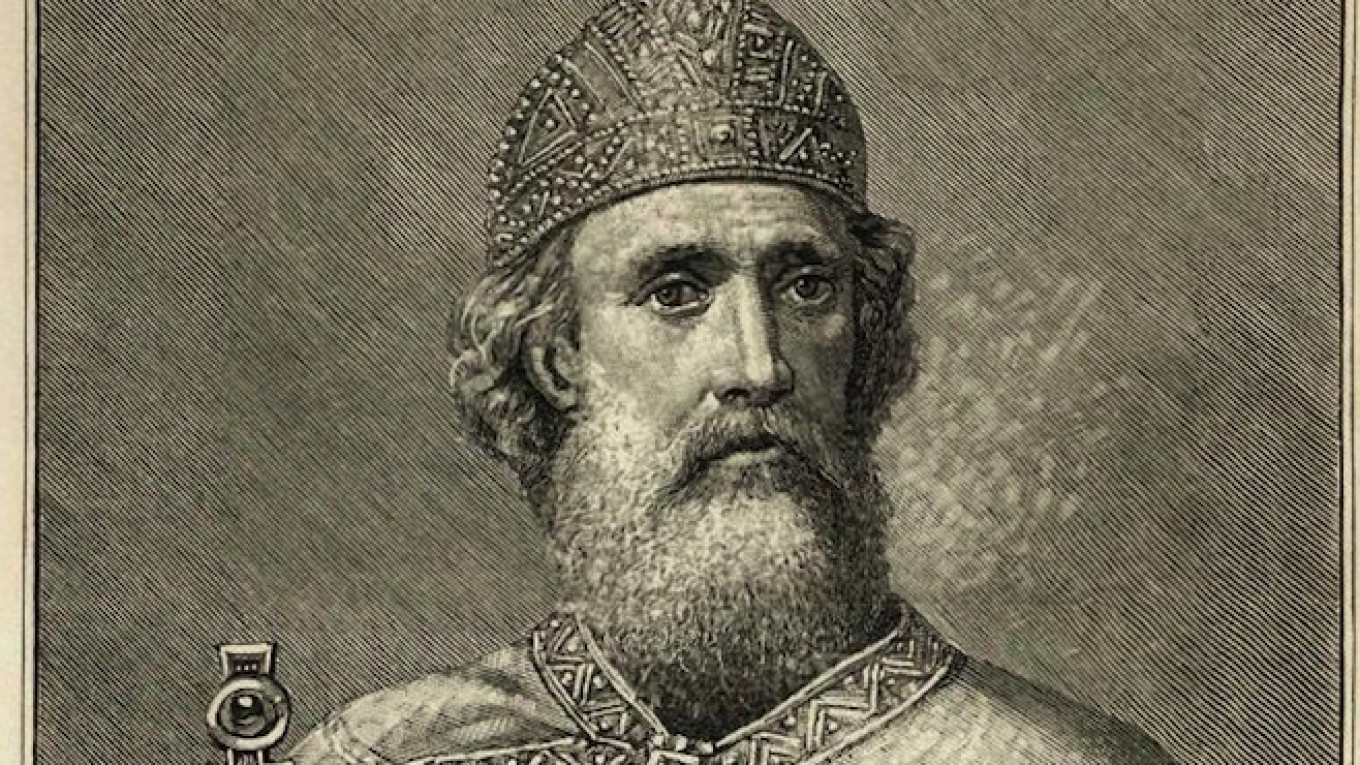

Tuesday marked the passage of a millennium since the death of Vladimir the Great. As both Kiev and Moscow honored the occasion with high-profile celebrations, leaders of each took advantage of the opportunity to emphasize the strength of their own countries' ties to the medieval ruler.

Prince Vladimir is revered for having introduced Christianity to the Kievan Rus, a federation of Slavic principalities that at times included portions of Russia, Ukraine and much of the former Soviet space.

In 988, Prince Vladimir was baptized in modern-day Crimea, converting from Slavic Paganism. He went on to Christianize the Kievan Rus, declaring Orthodox Christianity the official religion of his people.

According to the Kremlin, sometime between the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Prince Vladimir was “made a saint equal to the apostles by the Russian Orthodox Church.” He is celebrated annually on July 15.

President Vladimir Putin marked the occasion in style this year, inviting some 400 members of the Russian clergy, state officials and public figures to a grand reception at the Kremlin.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko attended a church service at Kiev's St. Vladimir's Cathedral and a celebratory concert was held in one of the capital's central squares.

Though both festivities centered on one man, Moscow and Kiev offered divergent views of what it was that Prince Vladimir ruled over.

While the Kremlin referred to him in a statement as the Prince “who baptized the people of Rus into Christianity,” the Ukrainian presidential administration referred to him as the “Grand Prince of Kiev” who Christianized “Kievan Rus-Ukraine.”

Russian and Ukrainian historians interviewed Tuesday by The Moscow Times agreed that any version prioritizing the ties of one country over the other is erroneous.

Prince Vladimir ruled neither over Russia nor Ukraine; he ruled over an early medieval state that united many Slavic people, and which only centuries later would evolve into the nations we recognize today.

“Both Ukraine and Russia are attempting to claim their common history as their own. In the time of Prince Vladimir no one had ever even dreamt of Ukraine or Russia. [Kievan Rus] was in the very early stages of development,” said Igor Danilevsky, a history professor at the Higher School of Economics, a prestigious Moscow university.

While analysts interviewed by The Moscow Times agreed that the use of history as a means to accomplish political ends often leads to its distortion, they likewise agreed that this is nothing new. Many politicians have employed this strategy as a source of state-building and to bolster national identity.

Speaking at the Kremlin's celebration of Prince Vladimir, Putin said “Christianization was a key turning point for Russian history, statehood and culture. Our common duty is to honor this crucial state of Russia's development.”

“By halting internecine strife [between the different principalities making up Kievan Rus], by defeating external enemies, Prince Vladimir laid the foundation for the formation of a united Russian nation; in fact, he cleared the way for the establishment of a strong, centralized Russian state,” Putin told his illustrious audience at the grand Kremlin palace.

Beyond the Kremlin walls, numerous other Russian celebrations have been hosted in recent days to honor Prince Vladimir, in an apparent attempt to emphasize the country's link to the early medieval leader — who ruled from the capital of modern-day Ukraine.

Overall, the Russian state earmarked upwards of 274.5 million rubles ($4.5 million) for festivals, forums and renovations across Russia in Prince Vladimir's honor, the RBC news site reported last week.

On Monday, Putin visited the newly restored church of St. Vladimir at the Moscow Diocesan house, which in Soviet times hosted a studio where documentary films were produced.

The Russian authorities also courted a great deal of media attention in recent weeks by deciding to change the location of a massive statue of Prince Vladimir that has already been constructed, and which was meant to be erected on Vorobyovy Gory (Sparrow Hills).

The original plan was for the monument to overlook the city center, and to resemble a monument to the medieval prince that has towered over the banks of the Dnepr river in Kiev since 1853.

During his last visit to Ukraine in July 2013, on the occasion of the 1,025th anniversary of the Christianization of Kievan Rus, Putin had visited the monument with then-President Viktor Yanukovych.

Since then, much has changed.

A few months later, in February 2014, a popular uprising led to the Kremlin-friendly Yanukovych's ouster, and cleared the way for the current pro-Western government to take power.

Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula and a bloody conflict between pro-Russian insurgents and Ukrainian government forces has erupted in eastern Ukraine, claiming the lives of upward of 6,000 victims and leaving more than a million people displaced, according to the United Nations.

The Russian government was eventually forced to scrap plans to install the monument at Vorobyovy Gory due to public outrage with the notion that Moscow's would dominate a portion of the Moscow skyline. More than 60,000 people signed a petition disputing the planned location.

Moscow authorities have yet to choose a new location.

But as Moscow scrambles to showcase its ties to Prince Vladimir, Kiev is doing its best to sever that cord, Ukrainian historian Alexander Karevin told The Moscow Times.

“The Ukrainian government is attempting to claim Prince Vladimir as its own, making it seem as though he had nothing to do with Russia,” Karevin said in a phone interview from Kiev.

“Unfortunately, many people are afraid to talk openly about this fact in Ukraine right now” he said.

Putin addressed members of the clergy of the Russian Orthodox Church, led by Patriarch Kirill.

Poroshenko attended a service led by Patriarch Filaret, head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church's Kiev Patriarchate, which has remained severed from the same church's Moscow patriarchate since 1992.

While the Moscow patriarchate has many adherents in Ukraine, Kiev authorities have thrown its weight behind the notion of unifying the patriarchates into a single church.

Prince Vladimir was active on the territories of both present-day Russia and Ukraine; today's borders would seem alien to him, said Vladimir Kuchkin, head of the Center of Ancient Rus History at the Russian Academy of Sciences' Institute of Russian History.

“There were differences between numerous principalities of the ancient Rus, but all of them spoke a very similar language, and all of their rulers were related to each other by blood,” said Kuchkin, one of Russia's most prominent historians of early medieval Rus.

“Prince Vladimir came to rule in Kiev from Novgorod [an ancient city in present-day Russia], but we don't say that a Russian had conquered Ukraine at the time,” he said in a phone interview.

Contact the author at i.nechepurenko@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.