Anti-war Russians who fled abroad in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine are looking to the upcoming annual celebrations of the Soviet Union’s victory over Nazi Germany on May 9 in order to gauge the viability of returning home.

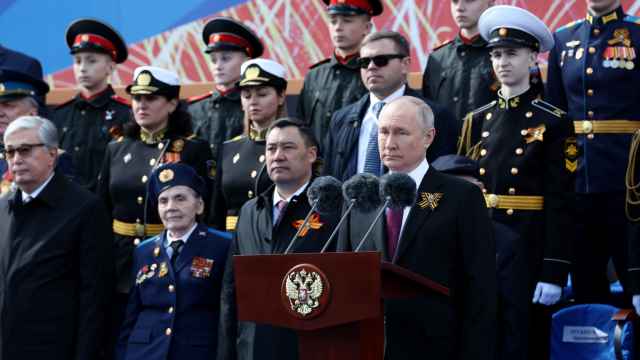

There has been much speculation that Russian President Vladimir Putin will use the occasion, which includes a large military parade through central Moscow, to make a major announcement about the war with Ukraine, perhaps even to declare victory.

“Right now May 9 seems like a date that you can pin some hope on,” said Olga, an IT professional who left Russia for Turkey soon after the invasion began and asked for anonymity to speak freely.

“Putin’s going to have to say something about the war,” she said. “It’s a question of what they are going to frame as a victory.”

Tens of thousands of emigre Russians are currently living in countries including Armenia, Georgia, Turkey and Latvia after fleeing abroad following the invasion of Ukraine in fear of conscription, political persecution and the economic fallout of the fighting. While some do not plan to return to Russia until the end of the regime, others are anxiously tracking developments in Moscow and trying to calculate when it might be safe to go back — if just to collect belongings and plan a more permanent emigration.

One Russian officer-in-reserve who works in advertising and flew to Turkey shortly after the invasion to avoid possible conscription said he was planning to go back to Russia for the May 9 holidays in order to see family and collect some possessions.

“I will be happy if I’m mistaken, but I think for Putin, May is very important… I think Putin imagines the victory parade to be like 1945,” he said, requesting anonymity to speak freely. “We’re expecting something bad — all of us here in Turkey, maybe not on that day in particular, but in the run-up to it.”

The use of symbolic dates has been significant throughout Russia’s military operation in Ukraine, with the invasion beginning the day after Defenders of the Fatherland Day, which marks the anniversary of the founding of the Red Army.

Much of the Russian campaign in Ukraine has also been saturated with historical analogies, particularly World War II imagery. Russian officials regularly accuse Ukraine of being a Nazi state, and Russian troops have raised World War II-era military banners over buildings and towns captured from Ukrainian forces.

Since the 1960s, Russia’s annual May 9 holiday has traditionally been marked by large military parades, large marches in major cities and other public events. This year, fighter jets will fly over central Moscow in the shape of a “Z,” the symbol that is widely used to show support for Russian troops in Ukraine.

“Putin is obsessed with history, and the symbolism of the cult of Victory Day in Russia,” said Russian foreign policy expert Anton Barbashin.

While the Russian army has enjoyed only limited success in Ukraine, seizing relatively small areas in the south and east of the country, many expect Putin to attempt to announce a sort of limited victory in Ukraine on May 9.

“Russia ended the war in Syria two or three times… they announced full victory, goals achieved, mission accomplished,” said Barbashin. “They could announce [on 9 May] that we won: Donbas is secure… but everything continues.”

Others believe the Kremlin could seek to harness the patriotic fervor of the Victory Day celebrations to put Russia on a broader war footing.

“It appears increasingly likely that rather than use it to announce victory, the Russian government will instead use 9 May as the day on which the ‘special military operation’ is officially framed as a ‘war’,” stated a report published last month by the Royal United Services Institute, a British think tank.

Turkey-based IT professional Olga said that if Putin did declare victory on May 9, it would raise her hopes of being able to return home to Moscow. But ultimately, she wants Russian forces to withdraw from Ukraine and regime change in Russia.

Whatever the hopes for a change in the situation on the ground by May 9, there is also significant evidence Russian forces are incapable of making the necessary gains on the ground in the run up to the symbolic day.

“I think people are becoming a little too fixated on May 9 as an end date for this war,” tweeted Rob Lee, a military analyst at the U.S.-based Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said Sunday that the Kremlin is not looking to end its war in Ukraine by Victory Day.

Fighting has increasingly spilled over into Russia in recent weeks, with apparent Ukrainian attacks on strategic facilities inside Russia. The border zone violence has even started to affect some Victory Day plans, with Belgorod region’s governor canceling Thursday so-called Immortal Regiment marches in nine districts bordering Ukraine.

Anna, a Russian who moved to the South Caucasus nation of Georgia after the invasion, said even if there was an official declaration of victory on May 9 it would not be enough for her to decide to go back to Moscow.

“The decision-makers in Russia are not very clear-minded, it’s nearly impossible to guess what they’ll say next,” she told The Moscow Times.

Like many of the Russians who fled abroad, Anna, who requested anonymity to speak freely, has been reluctant to cut all ties with Russia and is still making mortgage repayments on her apartment in Moscow.

“Of course I would like the war to end, but this [would not be] enough for me to return,” she said, adding that only when Putin was “in his grave” would she go home.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.