Today, Russia has no dearth of successful, celebrated women writers, but it wasn’t always so.

During the Soviet period women writers were perceived by the Communist Party and publishers as either subversive or beside the point. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, they negotiated a rather rocky coming-of-age. But now they are “a force in the world of letters,” writers of “confident craftsmanship, wide thematic range and high stylistic standards," as described by publisher, translator and writer Natasha Perova in her book “Slav Sisters.

In fact, women writers dominate the best-seller lists: Detective fiction writer Daria Dontsova has published more copies of more books than any other living Russian writer, followed by fellow crime writers Alexandra Malinina, Tatiana Ustinova, and Polina Dashkova.

The established writers Lyudmila Petrushevskaya, Lyudmila Ulitskaya, Tatiana Tolstaya, Nobel Prize winner Svetlana Alexievich and Olga Slavnikova win awards, publish in large editions, speak on radio and television, and pack halls at book fairs and lectures.

And then there is another group of women writers from the former Soviet republics who emigrated and write either in Russian or the language of their new countries: Dina Rubina, Tasha Karluka, Alisa Bialsky, Anna Likhtiman in Israel; Ellen Litman, Anya Ulinich, Olga Grushin, Lara Lapnyar, and Sana Krasikov in the U.S. Some are identifiably Russian in language, culture and subject; others have only a trace of a different sensibility — a rejection of political absolutes, a sensitive appreciation of anyone who is “other.”

Here are five young Russian women writers who are making their mark on contemporary fiction, film, and poetry.

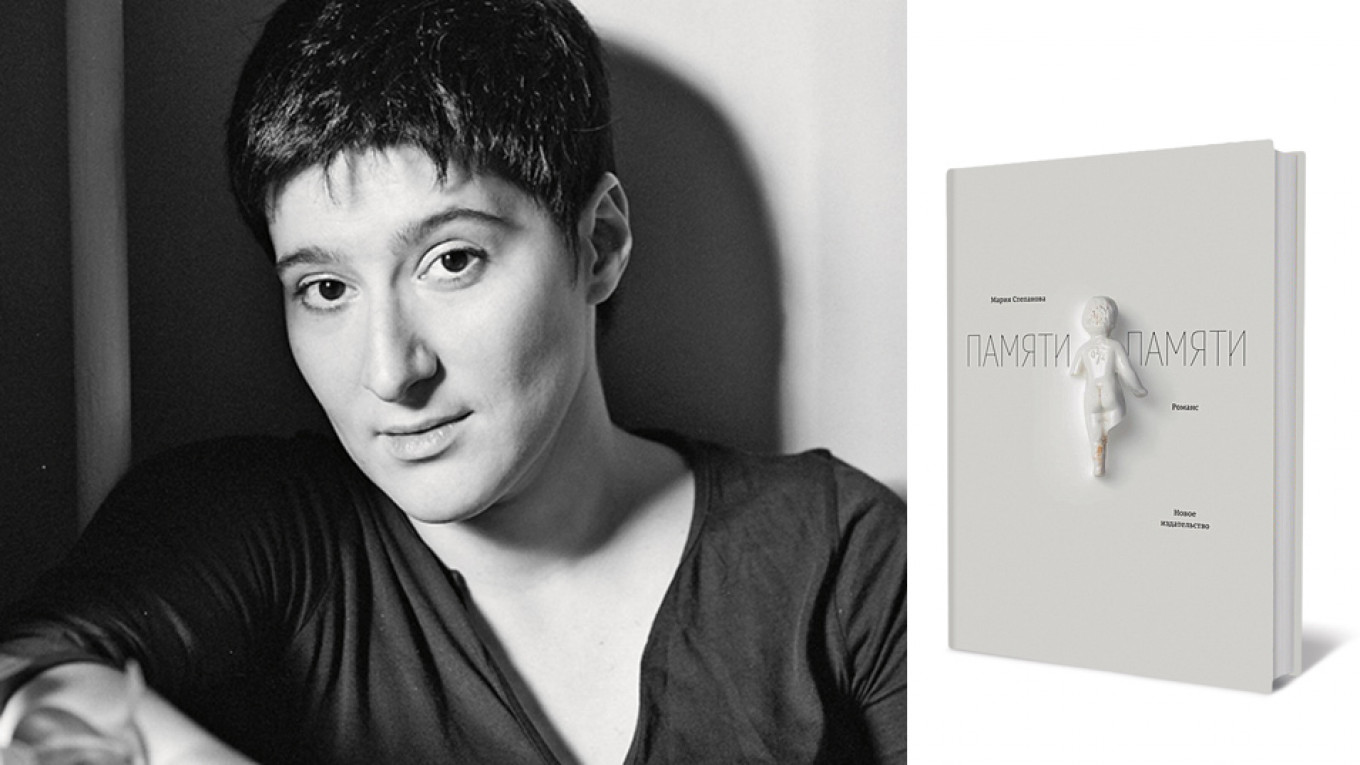

1. Maria Stepanova

Maria Stepanova (1972) is one of Russia’s most influential cultural figures, who seems to be constantly mastering new media and genres.

She was the chief editor of OpenSpace.ru and now heads Colta.ru, Russia's first online outlet funded solely by crowdsourcing. She is an acclaimed essayist, with two volumes of published works. And she is one of Russia’s finest contemporary poets, author of more than a dozen volumes of verse. Her poetic language pulls in and spits out all the voices and myths of Russia, past and present, mixing Biblical verse, pop song lyrics, 19th-century ballads, and all the glory and detritus of Russian letters.

In 2017, she moved to prose with the book “Post-Memory” (literally “Memory of Memory”), a kind of fictional non-fiction, the story of three generations of her family told through the preserved and remembered artifacts of their lives — the tale of people whose greatest achievement was simply to survive the perilous 20th century.

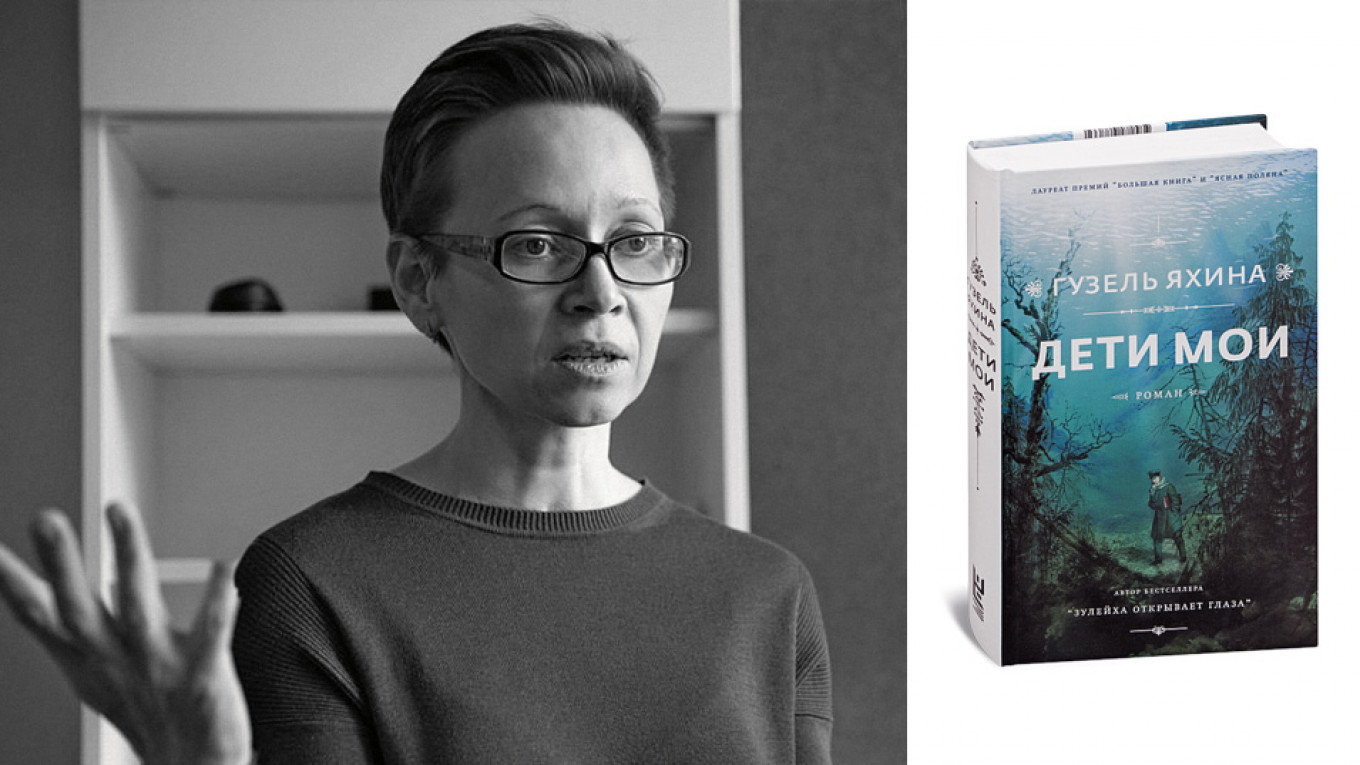

2. Guzel Yakhina

Guzel Yakhina (1977) grew up in Kazan.

Her first language is Tatar, and she only began to learn Russian when she went to school. Like many of her literary peers, she is a graduate of a film institute in screenwriting, but upon graduation she first worked in public relations and advertising while writing short stories.

In 2015, after being rejected by many publishing houses, she published her first novel “Zuleika Opens Her Eyes.” This is a fictionalized account of her grandmother, who was sent to Siberia as part of dekulakization in the 1930s. The Tatar context — words, folklore, traditions — opened up an unknown page in literature and history. The book won the Yasnaya Polyana and Big Book awards, has been translated into over 30 languages and is being made into a movie.

Her second novel, “My Children,” also deals with early Soviet history, personal freedom and the fate of the “little man” as she follows a teacher of German origin living near the Volga in the 1920 and 1930s.

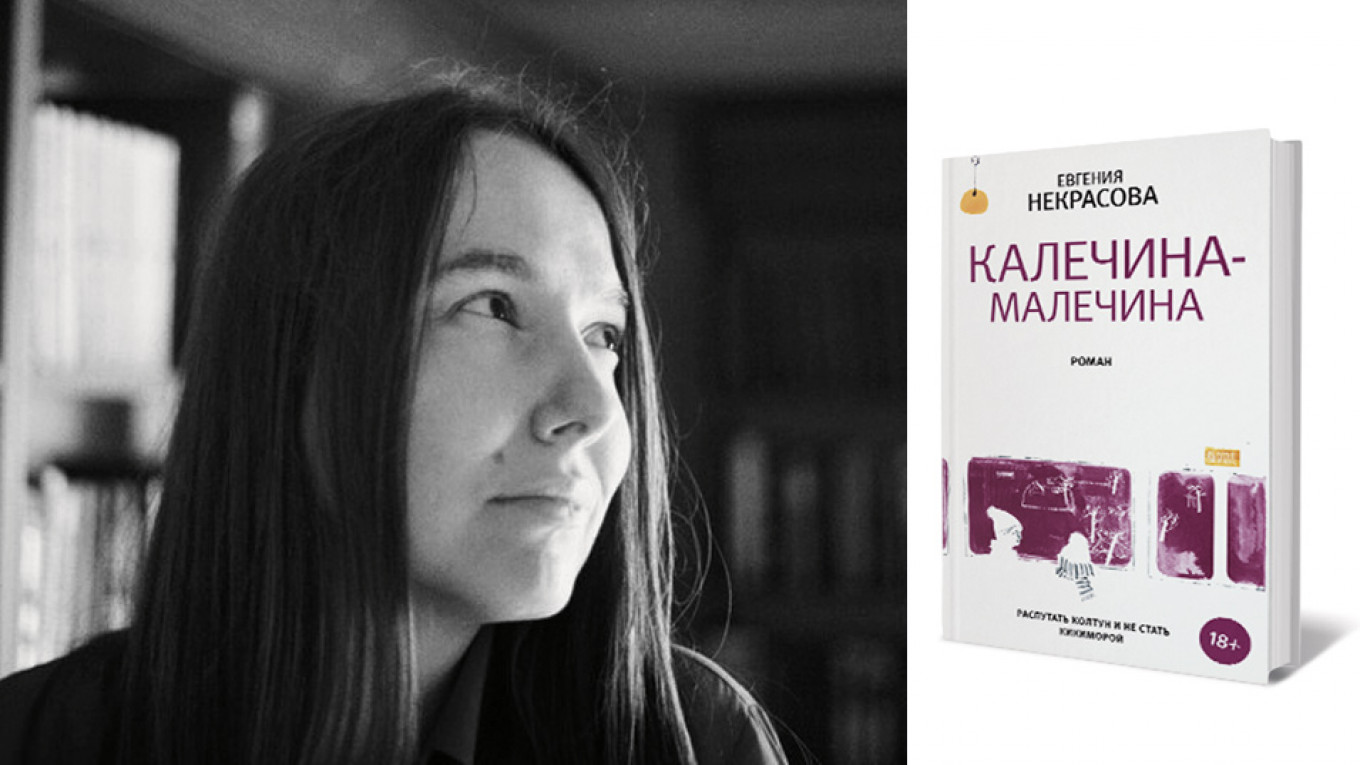

3. Yevgenia Nekrasova

Yevgenia Nekrasova (1985) is a writer and screenwriter who was born near Astrakhan and grew up outside Moscow.

She graduated from the scriptwriting department of the Moscow School of New Cinema, and began publishing her screenplays and short stories in professional and popular journals. Until recently, she was best known for her prose cycle “Unhappy Moscow,” which was awarded the Lycee Prize.

That was before her newest novel, “Kalechina-Malechina,” produced a sensation among readers and critics. The novel is about a little girl who lives in an ordinary high-rise in an ordinary small town with preoccupied parents and bullying classmates. But then extraordinary things happen: A snake comes out of the pipes, human figures emerge from blotches on the ceiling, and a house sprite that lives behind the kitchen tiles takes the little girl on a journey.

Nekrasova’s Moscow is magical, fantastical, funny and dangerous.

4. Anna Kozlova

Anna Kozlova (1981) breaks with her colleagues in education— she got a degree in journalism — but not in one aspect of her work.

She has established herself as one of the country’s most successful screenwriters, author of the hit television serials “Short Course for a Happy Life” and this summer’s “Ring Road.” Her writing is straightforward, unflinching and unsentimental. Her most recent television series, “Ring Road,” so shattered the image of the “traditional” Russian family that it was shown out of prime time, after 11 p.m.

But she is also one of the country’s most-read novelists. Her 2008 novel “People with Clean Consciences” was shortlisted for the National Bestseller. Her latest, sixth novel, “F20” — the medical services code for schizophrenia — won that prize in 2017. It is the mesmerizing story of an adolescent with schizophrenia, told from her particular, sometimes peculiar, point of view.

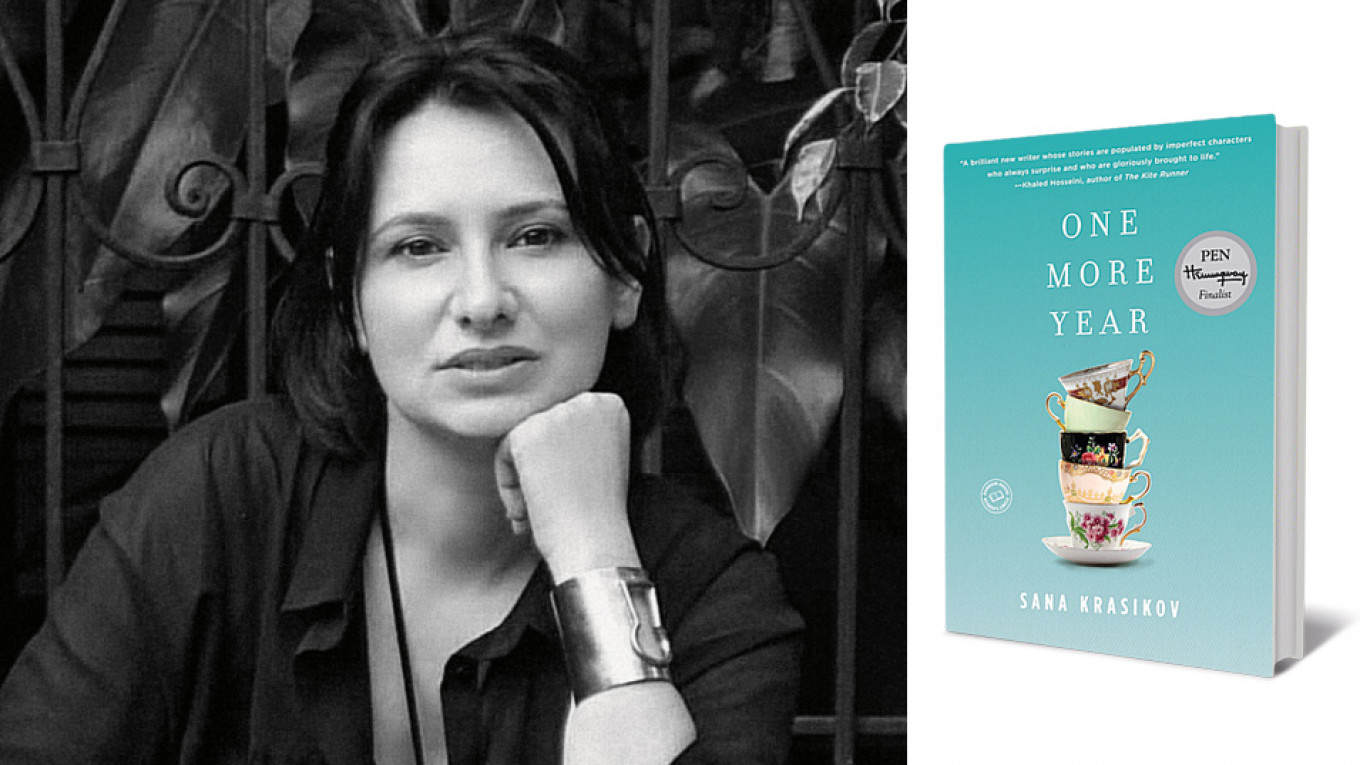

5. Sana Krasikov

Sana Krasikov (1980) was born in Ukraine and spent the first eight years of her life in Georgia before emigrating to the U.S.

After graduating from Cornell University and the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, she was promptly published by The New Yorker. She writes exclusively in English and does not call herself a Russian, or hyphenated, author.

But if her language is English, some of her characters and their surroundings are richly Georgian, émigré, Russian or Soviet. Her first collection of short stories, “One More Year,” describes the lives of Georgian and Russian émigrés abroad or back in their changed homelands.

Her second novel, “The Patriots,” follows three generations of an American family whose members emigrate to the Soviet Union, back to the U.S.and then back to the new Russia. Her latest short story in The New Yorker, “Ways & Means,” describes a #MeToo relationship that has nothing to do with Russia, except, perhaps, that it is written with the sensibility of someone who knows the dangers of denunciations, certainty, slogans and labels.

A version of this article appeared in our special "Women in Focus" print issue. For more in the series, click here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.