Swedish ambassador to the U.S.S.R. Staffan Söderblom met with Josef Stalin only once — in 1946. Something important must have been on the agenda: Stalin generously set aside an hour for this meeting in his schedule.

He would ask the ambassador during the meeting whether there was a particular issue he wanted to address. There was one, in fact: The young Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg had disappeared a year before in Budapest; the Soviets were suspected of capturing and imprisoning him.

But Söderblom would never confront the Soviet dictator about Wallenberg’s disappearance; instead, he would say that, in his opinion, Wallenberg apparently died in an accident in Budapest, and Soviet authorities, most probably, didn’t have any information about his fate. Stalin ended the meeting in five minutes rather than the allotted hour.

Only 11 years later, in 1957, Soviet authorities would officially admit to arresting Wallenberg in 1945 and placing him in prison. What happened to him after that has remained one of the biggest World War II mysteries up until today. Despite the considerable efforts of Wallenberg’s family and both Russian and Western historians, who have been trying to find the answers for almost seven decades, the puzzle still misses numerous pieces. Russia’s overall reluctance to open KGB archives and reveal secrets of the terror era to the public has significantly slowed down the investigation.

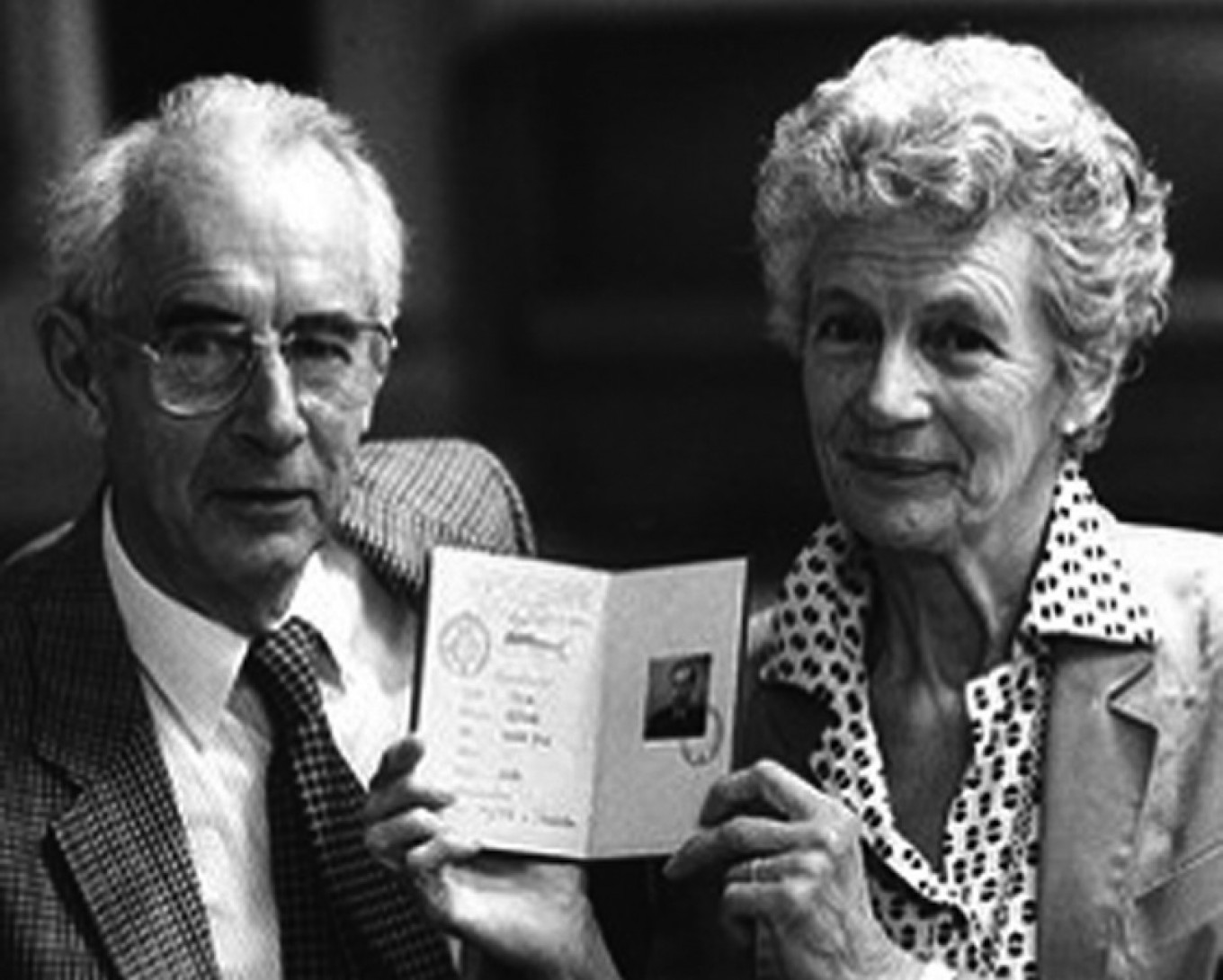

This year researchers might be closer than ever to obtaining answers. On Sept. 21, Wallenberg’s nieces Marie Dupuy and Louise von Dardel traveled to Moscow with a group of researchers and lawyers to meet with Russian officials and submit the list of questions, important documents and testimonies required to fill in the gaps of what is now known as the Wallenberg case. They met with the Foreign Ministry and Federal Security Service (FSB, successor of the KGB) officials and were promised full cooperation and all the archival data needed to solve the mystery.

If the promises are empty, researchers — after having joined forces with the Team 29 legal association that specializes in freedom of information issues — are ready to take necessary legal steps to obtain the information they need.

“We are still very much focused on a purely research approach. But we are now trying to take this discussion to another level. If they don’t respond to our request this time, we will have to take legal steps to insist on getting the necessary information,” Susanne Berger, historian and founder of the RWI-70 research initiative, told The Moscow Times.

Holocaust Hero Vanishes

Raoul Wallenberg, a 32-year-old secretary of the Swedish legation, arrived in Budapest in 1944. His mission was to help Hungarian Jews escape persecution by Nazi Germany, and the young diplomat was successful.

Wallenberg came from a prominent family of Swedish industrialists — their names were well-known both in Europe and in the Soviet Union. With a diplomatic passport in his hands, Wallenberg wasn’t afraid to openly help Jews in the capital of Hungary, then occupied by the Nazis. “Raoul spoke fluent German and had a way with German officers in Budapest,” says Louise von Dardel. “He could talk to them as if he was a top-rank official that they needed to obey, and they often did.”

He issued Swedish passports and visas to Jews, employed them in a company he had set up, provided them with food, medical care and places to live. According to various estimates, he managed to save 20,000 to 100,000 Hungarian Jews during his posting.

On Jan. 14, 1945 he went to meet with the members of Hungary’s interim government in the city of Debrecen. He also planned to contact the Soviet army that had entered Hungary in 1944 — in order to discuss the security of the Jewish protected houses, says Berger: “As a diplomat of a neutral country, with his diplomatic passport, he felt safe enough to do it.”

Both Wallenberg and his driver disappeared on that day.

For years after that, the family didn’t know what to believe. “Different information about Raoul’s fate came all the time,” Louise von Dardel recalls. “Some told us that he died when Budapest was bombed, some said he was in a car accident.”

Initial requests sent to the Soviet officials brought little clarity. A news brief published in The New York Times in November 1952 reads: “Russia informed Sweden at the time [in 1945] that the army had taken care of Mr. Wallenberg during the general confusion but that he had later gone away. In Sweden, the belief persisted that he was held prisoner in Russia. Former Soviet political prisoners have said they had talked with him in Russian labor camps. A Foreign Ministry spokesman said: ‘We know he is alive.’”

Over the next five years, Soviet officials repeatedly said that Wallenberg was not on Russian soil and that they had no knowledge of his location. Swedish authorities, Wallenberg’s nieces say, did little to get him back. “They didn’t even try to exchange him,” says von Dardel. “And then the Swedish ambassador met with Stalin and presumed Raoul dead. So Russia is not the only one to blame here.”

In 1957, the Soviet government officially admitted that Wallenberg was arrested in 1945 and held in the custody of the Ministry of State Security (MGB). On July 17, 1947, Wallenberg, 35, died of a heart attack in the Lubyanka prison, they said, citing a report by Alexander Smoltsov, head of the prison’s medical department.

This story, researchers believe, is most likely a lie.

Alternative Truths

Many things about Wallenberg’s alleged death just don’t add up. Smoltsov’s report states that heart attack “seems to be” the cause. It also says that no one performed an autopsy on the corpse. The MGB head at the time, Viktor Abakumov, ordered Smoltsov to skip the autopsy and cremate the body. The lack of an autopsy means that Abakumov knew the real cause of death. It means Stalin knew the real cause, as Nikita Petrov, a historian of the Memorial NGO who also studies the case, pointed out during a September conference devoted to the Wallenberg mystery.

“What would he have told Stalin about this death and what caused it? He should’ve conducted an autopsy to find out and explain the death to Stalin. Stalin knows about this case — a case he needs to hide from the West. So how should Abakumov report this death? [The fact that he didn’t order an autopsy] means that Stalin knows what caused it, if Abakumov is not willing to find out,” Petrov said.

In recently published memoirs, former KGB chief Ivan Serov supposedly assumed that Wallenberg was “liquidated” — in other words, killed by special services without standing trial and being convicted. “I have no doubts that Wallenberg was liquidated in 1947,” Serov, who ran the KGB between 1954 and 1958, wrote in his diary. He quoted Abakumov, former state security minister, executed in 1954: The order to liquidate Wallenberg came directly from Stalin and then-Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, Abakumov allegedly said during one of his interrogations.

There was a letter from Abakumov to Molotov on July 22, 1947 — and it is highly likely that Abakumov talks about Wallenberg’s fate in that letter, researchers say. It is registered in the MGB mail journal, but the actual letter was never recovered in the archives. “However, documents like this one never existed in just one copy,” argues Vadim Birstein, a biologist, historian and member of the first International Commission on Raoul Wallenberg (1990-1991) headed by Prof. Guy von Dardel, Wallenberg’s half brother. “A similar released letter regarding the liquidation of another prisoner, the American Isaih Oggins, has a number — ‘four.’ It means there were at least four copies, and they should exist somewhere.”

Another contradiction to the official version is the Lubyanka prison interrogation registry for July 22-23, 1947, which FSB archivists released to researchers in 2009. Despite careful censoring, the document shows that all the prisoners somehow connected to Wallenberg — his driver that was arrested with him in Budapest, their cellmates — were interrogated on those days, then isolated for years.

Someone else, named “Prisoner No.7,” was interrogated on July 23. FSB archivists say that this “Prisoner No.7” is, most likely, Wallenberg — which means he may have been alive after the alleged day of his death. “Was he ‘Prisoner No.7’? We don’t know. The FSB refused to provide us with more documents that could help us identify this mysterious prisoner,” says Berger.

Other researchers suggest that Wallenberg could have survived the MGB imprisonment in the 1940s and been sent to a different prison. Marvin Makinen, a professor at the University of Chicago, was convicted of espionage in 1961 and spent two years in the notorious Vladimir prison. During that time, he moved cells often, and some of his cellmates told him about a mysterious VIP inmate, a Swede, who was kept in solitary confinement. Some said his name was Wallenberg.

In the 1980s, Makinen interviewed a former employee of the Vladimir prison who dealt with the VIP Swedish inmate. She recognized Wallenberg in a photo lineup. “Even though I never mentioned that name in the conversation with her,” Makinen said at a Wallenberg conference last week.

Gaps to Fill

Which of these theories is the most trustworthy? When it comes to this question, historians and relatives of Wallenberg are not ready to give a definitive answer.

Wallenberg’s nieces Marie Dupuy and Louise von Dardel shrug and smile when asked about it. “Our father [Wallenberg’s half brother Guy von Dardel] was a physicist — he operated with facts. Verifying things was of utmost importance for him. We were raised in a similar mindset, that’s why we need documents, confirmations,” says Dupuy.

Historian Susanne Berger agrees. “It’s time we moved from speculating to confirming,” she says. “It is difficult for me to say what I think of it. Sometimes I wake up and think that yeah, it is possible that Wallenberg lived longer, and the next morning I wake up and say: No, I really think he died in 1947 … Getting as many facts as we can and then making a conclusion is our best bet.”

So far the facts are these: Wallenberg was arrested by the Soviets, taken from Budapest to Moscow and locked in a cell in the Lubyanka prison. He was later transferred to another MGB prison — Lefortovo, but had been returned to Lubyanka by March 1947, where his trail ends.

Another question without an answer is why Wallenberg was arrested in the first place. The name, Wallenberg, was well-known to Stalin, says Birstein, because the Wallenberg family has been doing business with the Soviet Union since the beginning of the 20th century. Apparently, Stalin was the one to order the arrest. “SMERSH, Soviet military counterintelligence, acted upon Stalin’s direct orders. Abakumov [head of SMERSH and later the MGB] took those orders and reported back to Stalin,” says the historian.

After winning the war in 1945, the U.S.S.R. needed money, and one of the countries that could loan it was Sweden. “My personal belief is that Stalin wanted to use captive Wallenberg as a ‘bargaining chip’ in negotiating a loan or other economic issues,” says Birstein. “But after meeting with ambassador Söderblom on June 15, 1946, when he realized that Sweden didn’t want Wallenberg … Well. What do you think he did with a prisoner that no one needed?”

Access Denied

The FSB is uncooperative these days — they intentionally censor and withhold some documents, say historians. “Sometimes we request documents and receive censored copies of them, other times they just ignore us,” says Birstein. “It often feels like, aside from a bunch of obsessed researchers, no one wants to find out the truth.”

By the time this article went to press, the FSB hadn’t answered the request sent by The Moscow Times for comment on their cooperation with the research initiative.

Archives of Russian state bodies, in theory, should be much more open, says Daria Sukhikh, lawyer from the Team 29 informal legal association that helps the Wallenberg research. Russia has quite progressive laws on access to information, but they often just don’t work, and state organizations find excuses to deny access. Cases of state bodies denying access to their archives or documents should be considered by courts, but courts often take the side of powerful organizations like the FSB, Sukhikh said at a Wallenberg conference.

Unwillingness to open archives is often just an instinct for secretive bodies like the FSB, Ivan Pavlov, a lawyer and leader of Team 29, told The Moscow Times. “In addition, no one wants to set a precedent. Imagine: If they open one archive and reveal everything about one case, they would have to do it a lot more often,” he says. “Secrecy about historical facts helps manipulate them.”

Not Giving Up

On Sept. 23, members of the Wallenberg family, together with researchers, met with officials of Russia’s Foreign Ministry and representatives of the FSB’s Central Archive, Susanne Berger told The Moscow Times. “The meeting was very interesting and constructive,” she said. “It went better than we expected.”

Officials assured them that Raoul Wallenberg was an “exceptional” figure, and full resolution of his fate is very important, Berger added. Head of the FSB archive, Vasily Khristoforov, said that his department would “thoroughly review” the catalogue of open questions and pending research questions Wallenberg’s family handed over during the meeting. “He also indicated that the FSB Central Archive was ready to continue to work with independent researchers in their common effort to answer the remaining questions in the Wallenberg case,” says Berger.

Wallenberg’s nieces admit that trying to hunt down the truth is exhausting on many levels. It eats up a great deal of time, effort and money, they say. It is always somewhere in the back of their minds; they can’t stop thinking about it, even though they sometimes wish they could. “We do want to live our own lives at some point,” says Dupuy. “But at the same time we know that we can’t give up.”

If there are no comprehensive answers to the questions from the catalogue presented to the FSB archives, further actions will include formal complaints and possibly a lawsuit, say Team 29 lawyers.

“We are very stubborn,” von Dardel says with a laugh. “We are ready to go all the way up to [Russian President Vladimir] Putin if we have to.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.