The shadowy interests of Yevgeny Prigozhin — a Russian businessman and close associate of President Vladimir Putin — have just become a little clearer.

Over the past year, reporters from OCCRP’s Russian partner, Novaya Gazeta, tracked the registration details and movements of business jets linked to Prigozhin. They reveal significant Russian involvement and activity in Africa, and a mysterious trail of previously undisclosed European companies linked to Prigozhin.

For example, a Prigozhin-linked jet transported a Russian military delegation to Sudan right after the April coup that unseated the country’s president, Omar al-Bashir, whom Moscow initially backed.

In the Central African Republic, at least three Prigozhin-linked planes were making flights within days of the murder of Russian journalists who were in the country to investigate Wagner, a private military company also linked to Prigozhin.

Yet another jet was much less active for months, after its movements in the Middle East and Africa were revealed by Novaya Gazeta this February. Four days after the story was published, the plane flew to Berlin and disappeared from radar. In July, it reappeared with a new tail number and country of registration.

Prigozhin’s press office said it did not have the information to answer reporters’ questions, and the Russian defense ministry did not respond to reporters’ inquiries.

Putin’s chef — and more

Prigozhin’s profile has risen in recent years.

In early 2018, the secretive businessman was sanctioned and indicted by the United States for his financial support of the Internet Research Agency, a troll farm accused of meddling in the 2016 presidential election. This September, he was sanctioned again for attempting to influence the 2018 midterm elections.

The U.S. Treasury Department targeted three of Prigozhin’s jets, a yacht called St. Vitamin, and the front companies he used to manage them. Under the sanctions, any transactions or interaction with Prigozhin’s blacklisted assets — including granting the aircraft landing rights — exposes the service provider to U.S. sanctions.

Prigozhin is sometimes known as “Putin’s chef” because his restaurant group has catered the Russian president’s dinners with foreign guests, with Prigozhin personally serving Putin at some banquets.

But he is also believed to be behind the Wagner Group, a shadowy mercenary organization suspected of fighting on behalf of the Russian government in Syria and eastern Ukraine, and maintaining a strong presence in Africa. In July 2018, three Russian journalists who were in the Central African Republic to report on Wagner were murdered in an ambush.

Prigozhin is reportedly a key player in Moscow’s increasing efforts to grow its influence on the African continent.

Sudan for the Sudanese

This spring, Russia’s relationship with Sudan underwent a dramatic challenge. Protesters poured into the streets demanding regime change and the demonstrations lasted for months.

Russia initially continued its long-standing support for beleaguered President Omar al-Bashir, whose 30-year rule over the country was marked by oppression and human rights abuses. He had traveled to Russia several times over the previous few years, using the occasion of his visits to thank Putin for Russian military assistance and to ask for help against “the aggressive actions of the United States.”

Leaked documents indicate a Prigozhin-linked company was proposing strategies for how to crush the protests. The proposals outlined how to spread misinformation and hold public executions, CNN reported.

The day after the Sudanese Armed Forces removed al-Bashir from power and put him under house arrest, Putin’s press secretary Dmitry Peskov insisted that the Sudanese events were “an internal affair of Sudan and should be resolved by the Sudanese themselves.”

But just a week later, a group of high-ranking Russian military officials headed to Sudan’s capital, Khartoum.

Among its members were Igor Osipov, the commander of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet; Andrey Glushchenko, who has served as a military attache in Egypt; and Maxim Zelnik, reportedly a Ministry of Defense representative. The exact purpose of the visit is unknown, but presumably was related to rapidly developing events in Khartoum, where the military council now governing the country was facing continuing protests.

According to air traffic data obtained by reporters, the Russian military personnel traveled to Sudan on an Embraer ERJ-135 with the registration number M-SAAN. This corporate jet, as well as the company that owns it, were among the Prigozhin-affiliated entities sanctioned by the U.S. this September.

A week after the Russians’ visit to Khartoum, the jet once again traveled the same route from Moscow. This time among its passengers were Gamal Omar, who is now Sudan’s defense minister; and Abdelrakhim Khamdan Dagalo, а senior commander of the feared paramilitary Rapid Support Forces. The men were in Russia to meet with Alexander Fomin, the deputy defense minister. On that visit, Omar assured his Russian hosts that, despite the coup d’etat, Sudan’s armed forces would adhere to all previously established military agreements.

Prigozhin accompanied the Sudanese on the jet himself at least once, according to data obtained by reporters. In January 2019, Prigozhin, his son Pavel, and several Wagner fighters — accompanied by Sudan’s former UN ambassador, Daffa-Alla Elhag Ali Osman — used it to fly from Moscow to Khartoum.

Diamonds and death in Central Africa

The Central African Republic is devastated by war but rich in mineral resources. Prigozhin-linked companies are increasingly active in both the military and mining sectors in the central African country, according to numerous media reports.

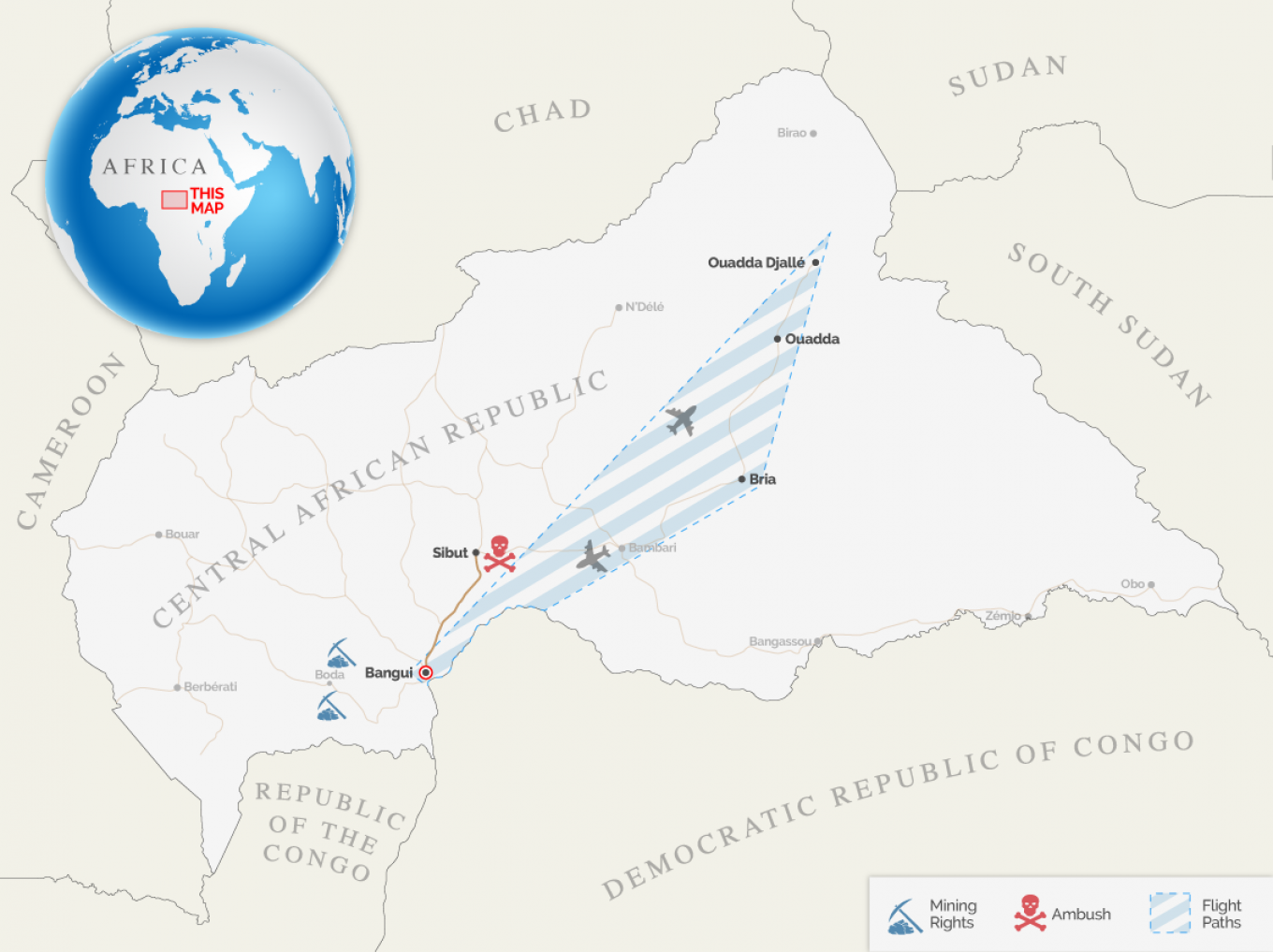

A document obtained by CNN shows that last year a company called Lobaye Invest was granted diamond and gold exploration rights in an area called Yawa, in the prefecture of Boda, for a period of three years. Another document shows Lobaye also has one-year exploration rights in the nearby area of Pama. According to the CNN investigation, Lobaye is linked to Prigozhin’s Concord group of companies — and soldiers from the Wagner Group, the Russian private military organization linked to Prigozhin, reportedly protect the mines.

Last year, three Russian journalists — Orkhan Dzhemal, Alexandr Rastorguyev and Kirill Radchenko — were in the Central Africa Republic to make a documentary film about the Wagner Group and other companies linked to Prigozhin. Two days after they arrived, on July 30, 2018, they were killed by armed assailants in a road ambush.

An investigation by the Dossier Center — an organization backed by exiled Putin critic Mikhail Khodorkovsky — concluded that a Central African Republic security official was likely involved in the murders and coordinated the attack with individuals employed by Prigozhin’s organizations.

Russia’s Investigative Committee insists that the journalists were killed during a robbery. After the murders, Prigozhin’s press service announced that the businessman had “no interests involving military or civilian projects in the Central African Republic, including gold deposits.”

Flight information obtained by reporters shows that a Hawker 125-800B business jet registered in the Cayman Islands with the tail number VP-CSP, flew to Bangui, the Central African Republic’s capital, 10 days before the attack on the journalists. The U.S. Treasury Department has listed the plane as belonging to Prigozhin via Linburg Industries Ltd, a Seychelles company.

Two other aircraft linked to Prigozhin flew between Bangui and the remote destinations of Ouadda Djalle and Bria during the last week of July 2018. The two Cessna planes — with tail numbers RA-67717 and RA-67581 — were not among the aircraft sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department as Prigozhin’s assets. The planes are, however, owned by the companies M-Finans and M-Invest, which are also reportedly part of Prigozhin’s Concord group of companies. These destinations are far from Yawa and Pama, where Lobaye holds mining rights.

European connections

After Prigozhin was first sanctioned by the United States in 2016, he dismissed the measures as inconsequential.

“I have no foreign assets, I vacation on Russian territory, and I have no connections with America and Europe, so none of this matters to me,” he said.

The trail of companies behind Prigozhin’s VP-CSP jet suggests otherwise.

The plane is owned by LinBurg Industries Ltd, a company registered in the Seychelles. LinBurg is run by Andrey Yushchin, a man who has worked for six years as head of security for Prigozhin’s well-known Russian restaurant holding, Concord, according to his resume.

LinBurg itself would be just another shell company if it hadn’t opened a branch in the Czech Republic in April 2017, making it the first known Prigozhin-linked business foray into Europe. In the founding documents of its new branch, the company states that the company its expanded to the Czech Republic to enter the European market.

LinBurg’s Czech branch was registered by a company called All4business.cz, which provides virtual addresses and other corporate services for firms that want to set up shop in the Czech Republic.

In the Czech business registry, LinBurg claims its primary purpose of business is “rental of real-estate property, flats and commercial sites.” However, according to the local land registry, LinBurg does not own a single property in the country.

“We indicate ‘property rental’ automatically for most companies we help set up,” explained Alexander Adamov, the owner of All4business.cz.

All4business.cz also registered two other new companies alongside LinBurg: Concorde Ventures, a name that echoes Prigozhin’s Russian restaurant group, and Wings Trade & Consulting. Ivo Zutis, a Latvian citizen, appeared on incorporation documents of all three companies – all headquartered at the same Prague address, a nondescript historic building where All4business.cz is registered.

Adamov told OCCRP he had personally met Zutis in Prague, but claimed he could not remember anything about his Latvian client.

“I have a lot of clients. I don’t remember anything particular about him,” he said.

When reporters reached Zutis by telephone, he confirmed he was connected to the Czech companies. He did not seem surprised by a question about his links to Prigozhin, but declined to discuss the relationship further, saying he preferred to meet in person. He then stopped responding to inquiries.

Two months after Concorde Ventures was established, Zutis sold a 99% stake to a Cyprus-based offshore company, Renitavo Investment Ltd, whose ownership is unknown.

He also vacated the directorship of LinBurg. The Czech branch of the company is now headed by Vitaly Murentsov, a Russian based in St. Petersburg. Little is known about him except that, through a chain of Russian companies, he is connected with other people listed as directors or founders of firms reportedly linked with Prigozhin’s organizations.

All4business.cz fired LinBurg and Concorde as clients and reported them to authorities earlier this year after they stopped paying for the use of the virtual Czech address. Adamov, the company head, said he had been surprised to learn that LinBurg appeared on a U.S. sanctions list.

“We don’t have anything to do with them anymore, as we already reported to the court the Czech LinBurg company’s headquarters is not valid,” he said, adding that he had never heard of Yevgeny Prigozhin.

“How was I contacted by a company representative? Maybe one of our former clients recommended us. We advertise on the Internet. Honestly, I don’t really care how it happened, since we provide only virtual headquarters,” Adamov said.

Prague’s business registry court liquidated Concorde Ventures in June. However, LinBurg is still registered in the Czech Republic. Adamov said he believed this was because of its more complex corporate structure.

“In fact, a Czech court cannot liquidate the LinBurg Czech branch on its own, as it’s a subsidiary of the parent company,” he said. “That’s probably why it takes time and why the company still appears in the Czech company registry.”

It is unclear what effect the U.S. sanctions against Prigozhin will have on his interests in the Czech Republic.

Pending EU anti-money laundering legislation should make it “clearer what are the specific connections of Evgeny Prigozhin to businesses in the Czech Republic and elsewhere in the EU,” said Petr Jansky, a lecturer at Charles University in Prague who studies tax havens and illicit financial flows. EU member states must implement the new rules, which will increase transparency into who really owns companies and trusts, by January 2020.

“The public gives companies the privilege of limited liability and it should in turn receive corporate transparency on who their beneficial owners are and what activities they carry out. As these three companies show, this is obviously currently not the case,” said Jansky. “This is a glaring example of when corporate transparency can have far-reaching effects on the national security of the Czech Republic, Europe, and their allies,” he added.

Return to the homeland

Novaya Gazeta first began tracking Prigozhin’s luxurious Hawker 800XP business jet last year, when it was still flying under the tail number M-VITO. Prigozhin’s children had shared photos on board the jet on social media, catching the attention of Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, as well as journalists.

In February 2019, Novaya Gazeta exposed the aircraft’s real owner — Beratex Group, which the U.S. sanctioned later in September — and its regular flights to Syria, Lebanon, and Africa.

M-VITO’s flight patterns showed that from December 2016 to January 2019, one of the most popular destinations for the jet was the Middle East — second only to the Moscow-St. Petersburg route.

During that period, M-VITO flew to and from Beirut 48 times. In most cases, Beirut was simply a transit point to Syria and Africa, details show. The jet was spotted over Syria 21 times. The Wagner Group’s presence in Syria has been widely reported. In 2016, as reported by the St. Petersburg-based news outlet Fontanka, the Russian energy ministry, represented by Prigozhin-linked company Euro Polis, entered into a contract with the embattled Syrian government, promising to liberate the country’s oil and gas fields in exchange for a quarter of the revenues from oil and gas production. The fighting would be carried out by Wagner, with the costs refunded by Syrian government, according to the memorandum. In 2018, Wagner mercenaries engaged in a four-hour battle with U.S. troops, fighting on behalf of Syrian pro-government forces.

In Africa, M-VITO was detected in the data for the first time over Egypt in November 2017, at a height of 11,000 meters. This height indicates that the plane was continuing its route and not coming in to land, according to an aviation specialist. Beyond that point M-VITO was either outside the radar coverage zone or turned off its transponder. According to the tracking data, the business jet “disappeared” above Egypt, near or above Libya 27 times. In one case, the destination was confirmed by Kenyan media, which reported that Prigozhin’s plane flew from Sudan to Nairobi, the Kenyan capital, on December 17, 2018.

Four days after the February publication of Novaya Gazeta’s report on the plane’s activities, M-VITO landed in Berlin and no more accessible data about its movements appeared again.

In April, the plane was de-registered from the Isle of Man, where it was domiciled since 2012. And in July, the aircraft’s tail number was changed to RA-02791 and registered to Russia.

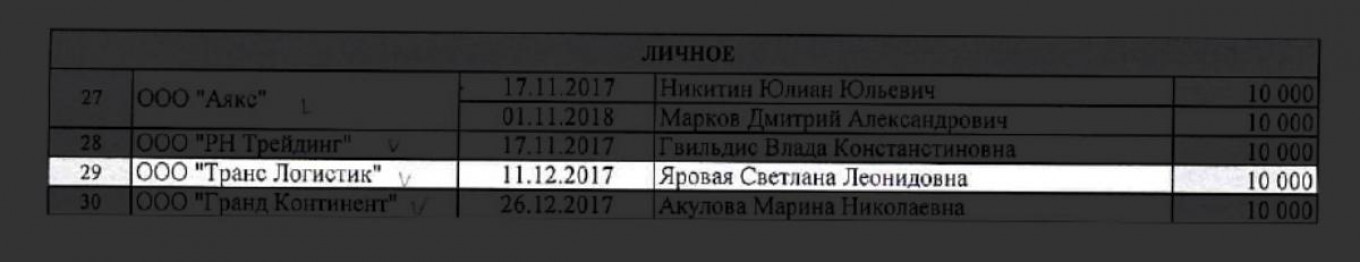

The jet’s new owner, a St. Petersburg-based company called Trans Logistic — as well as its head, Svetlana Yarovaya — both appear on an internal list obtained by the Dossier Center and viewed by reporters that indicates businesses and nominee structures supposedly linked to Prigozhin’s group of companies.

On the document, people and companies are grouped by categories. For example, companies marked as related to Syrian projects are grouped together. Both Trans Logistic and Yarovaya appear in the “Personal” section.

Yarovaya did not respond to requests for comment.

Jason Shea and Vlad Lavrov contributed reporting.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.