MINSK – Opposite the Minsk Sports Palace, a brutalist 1960s indoor ice hockey arena in the Belarusian capital, a column of around fifty men and women walks behind a police officer in a black balaclava covering everything but his eyes. Some are carrying their children.

The officer leads them to the parking lot opposite the rink, where they board the many taxis and buses that have swarmed the area. The vehicles will take them on the four-hour drive to Grodno, a city on the border with Poland.

From there, they will attempt to walk through the cold, dense forests along the border to get to a buffer zone dubbed “the jungle” by migrants stuck between the two nations. They will be met by thousands of heavily armed Polish border guards who have already erected a fence topped with razor wire and approved the construction of a wall.

Groups like this could be seen leaving the small square opposite the sports palace every half hour on Thursday afternoon.

Estimates put the total of migrants currently in Belarus between 8,000 and 15,000, scattered around Minsk and the country’s western border. Walking around the capital, the numbers are striking.

Many of the people congregating around the sports palace on Thursday said they had just flown in from airports in cities across the Middle East.

Those opportunities became more limited on Friday when both the Turkish and Belarusian flagship airlines announced they would stop Iraqi, Syrian and Yemeni citizens flying from Istanbul to Minsk. However, on the same day, more migrants arrived in Minsk on flights from Dubai and Beirut.

Others, like Ahmed, who was sitting near the sports palace with a few friends, have been in Belarus since September.

Ahmed recently returned from “the jungle,” a makeshift tent village in the forest between the Belarusian and Polish borders.

“It was awful there, no water or food, so we decided to restock and sleep a bit. Tomorrow we will go back, what else can we do?” he said, his bloodshot eyes showing the lack of sleep.

Ahmed said Polish guards had beaten up his friends when they approached the border.

The UN refugee agency has said at least 10 migrants are believed to have died so far as a result of the harsh conditions in “the jungle.” Polish media reported that on Wednesday night, a 14-year-old Kurdish boy froze to death.

Like most migrants, Ahmed came to Minsk on an expensive package tour organized by a travel agency in Iraq. He said he paid a firm in Lebanon $3,000 and has since run out of money, while his one-week tourist visa has also expired.

Since coming back from “the jungle,” his group has been living on the streets of Minsk in sleeping bags and tents.

“We can’t go home anyway, we have given up everything to get here,” he added.

The EU has accused Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko of using migrants as a weapon to punish the West for sanctions imposed after his disputed 2020 election victory by orchestrating the crisis on the borders of member states Poland and Lithuania.

For many locals, seeing migrants in cafes and fast-food chains, strolling around shopping malls and sleeping in underpasses is unfamiliar. Before the crisis, Belarus rarely admitted migrants, as the country’s visa policy was notoriously strict.

“Minsk has changed completely,” said Anna, a waitress working at Vasilki, an upscale restaurant chain serving traditional Belarusian food.

“It’s like we don’t live in Minsk anymore. It’s strange,” she added.

Last month, Belarusian media reported the first death of a migrant in the capital, saying a 35-year-old Iraqi man collapsed outside a shopping mall.

As many more migrants like Ahmed return from the border disillusioned and hungry, but unwilling to go back home, the unresolved situation could become a serious problem for Lukashenko.

While the situation has irritated some locals, many in Minsk are treating it as a business opportunity.

The Hotel Sputnik was fully booked. Arabic and Kurdish could be heard in the main lobby of the imposing but shabby five-story building, and throughout its dimly lit corridors.

Other hotels, including the Crown Plaza in the city center, also said they were working at full capacity. Migrants said that Belarusian and local tour agencies booked week-long stays in hotels across the city for them prior to departure as part of their travel packages.

Anna, the receptionist at Sputnik, said the influx of new customers was a welcome change.

On top of the pandemic-related slowdown, Belarus, which used to attract some Western tourists and business travelers, has been rocked by instability over the past 18 months.

Last year, the country saw its biggest ever anti-government protests following Lukashenko’s controversial re-election. And this summer Belarus found itself further isolated when the EU banned Belavia from its airspace after Minsk forced a Ryanair flight to land in order to allow it to arrest an opposition journalist.

“It was very quiet during the pandemic. Tourists stopped coming, but now it’s busy every day. It’s good for business,” Anna said.

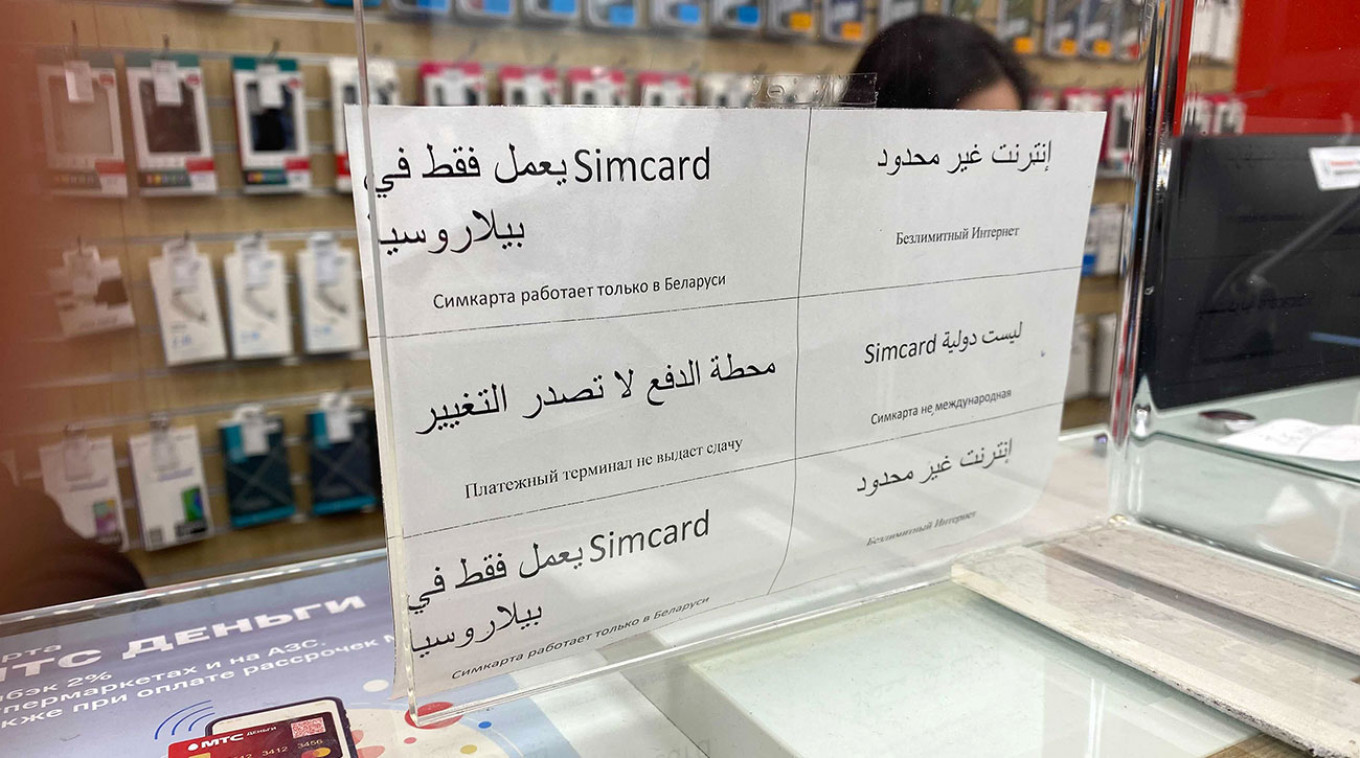

Phone shops, including those run by Russian telecoms provider MTS, are displaying Arabic signs in their windows for migrants buying local sim cards before they head west.

But the biggest winners are the taxi drivers.

Sergei said he charges $150 per trip to Grodno, and estimated he makes at least four trips a day.

“I am earning more this month than I did in the previous six. But things have got a bit tougher lately,” he added, explaining that Belarusian border police have started turning back taxis carrying migrants as they approach the border.

Now, he and his colleagues bring migrants to a gas station near Grodna, where Syrian, Iraqi and Belarusian handlers lead them over the border to the forest in the buffer zone.

A number of media have previously reported on Belarusian soldiers helping migrants to cross the border. Videos posted online on Friday night appeared to show Belarusian soldiers destroying the barrier at the border.

It’s not just Belarusians who are looking to profit from the crisis. A small industry has sprung up in the Middle East to help coordinate the transfer of migrants to Belarus with Belarusian tourist agencies and consulates.

Standing outside the Skala shopping mall in the east of Minsk as night fell, a group of Syrian migrants huddled together to smoke cigarettes.

They came from As-Suwayda, a Syrian city near the border with Jordan and belonged to the Druze ethnic minority. They said they fled Syria to avoid mandatory two-and-a-half-year military service.

Each paid $5,000 to a Syrian middle man in Damascus, who in turn paid a Belarusian travel agency for a package tour that was meant to include a hotel and visa as well as help on the ground. Once in Minsk, they felt they had been cheated and their middle man cut off all communication.

“The bastard lied to us,” said Walid, who worked as an engineer in Syria.

“He promised a hotel for 10 days, but 10 of us were huddled in a tiny room next to a brothel for only three nights. And now he has stopped answering his phone,” Walid said, showing the unanswered calls on his phone.

The men had come to the mall to buy water bottles, SIM cards and torches. They were planning to take a taxi to Grodno on Friday morning, where the dangerous part of their journey would begin, and Walid was already anxious.

“We aren’t welcomed here or back home. Nowhere.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.