Russia has been a lot of things over the past century: the crucible of Communism, an “evil empire,” an experiment in market economics, an international pariah.

Now, as he settles into his final constitutional term as president, Vladimir Putin must decide what Russia will be next — and the options aren’t great.

Oppressive governance and an aging population have left the economy with little capacity to grow, threatening a period of stagnation that could turn the people against him. Putin says he wants a breakthrough, yet the crucial conditions — the sanctity of private property and personal freedom — are precisely what he can’t deliver: The Kremlin elite derive their wealth and position from violating them.

Putin’s predicament has global significance, given Russia’s nuclear arsenal, role in geopolitics and penchant for foreign adventures. Hence, it’s worth trying to understand how the country got here. That requires looking back a couple decades, to the chaotic environment that made the rise of an authoritarian leader all but inevitable.

Stability and Growth: 2008 — 2008

At the end of the 1990s, Russia was grappling with the collapse of its unprecedented effort to establish capitalism and liberal democracy in a country that had never known either. With no institutions to replace Soviet control — and with inadequate support from the West — the process had devolved into a free-for-all. Those ruthless or lucky enough to grab valuable assets had become oligarchs, who used the justice system and the media as weapons in endless battles for dominance. Ordinary Russians struggled to adapt, often going for months without pay or pensions. All this culminated in the catastrophic default and devaluation of 1998, which crippled President Boris Yeltsin and opened a power vacuum.

By New Year’s Eve 1999, when Yeltsin resigned, Russians were desperate for order. So they largely supported their new president, Vladimir Putin, as he moved aggressively to consolidate power. Over the next several years, he exiled or imprisoned oligarchs such as Vladimir Gusinsky, Boris Berezovsky and Mikhail Khodorkovsky, reestablished government control over broadcast media, subjugated the parliament and turned previously elected regional governors into appointed officials. An implicit social compact emerged: If the people would stay out of politics, Putin would deliver stability and growth.

To his credit, Putin pushed through some much-needed reforms. He entrusted fiscal and monetary policy to a group of economic liberals led by Alexei Kudrin, a colleague from the St. Petersburg city administration. They simplified the tax system, introducing a flat 13 percent rate on personal income that coaxed people onto the rolls. They overhauled the government budget system, imposing greater discipline at the federal and regional levels. And they created a stabilization fund to insulate state finances and the economy from swings in the prices of oil and gas, Russia’s biggest exports and sources of government revenue.

From 2000 to 2008, the economy boomed. Gross domestic product per person, adjusted for inflation and purchasing power, nearly doubled. Although driven largely by the devaluation of 1998 and a sharp increase in the price of oil, the performance lent legitimacy to Putin’s version of “managed democracy.” He had honored his end of the bargain. At the end of 2008, his approval rating exceeded 80 percent.

Prosperity provided cover for a major redistribution of wealth. As state companies absorbed the assets of the ousted oligarchs, a new elite emerged at the commanding heights of the economy. Its members had ties to Putin, often from his KGB service or his time as first deputy mayor of St. Petersburg. One colleague, Alexey Miller, became the chief executive of natural-gas giant Gazprom, which acquired media assets from Gusinsky and an oil company from Berezovsky. Igor Sechin, who had been Putin’s chief of staff in St. Petersburg, headed the state-controlled Rosneft, which took Khodorkovsky’s oil assets and much more.

The asset grab epitomized a type of predation that pervades Russia. The aggressor can be a member of the Kremlin elite, a police official, anyone with the right connections. He identifies a target and recruits investigators to build a criminal case — tax evasion for Khodorkovsky, embezzlement for Gusinsky. No matter how flimsy the charges, resistance is futile. Judges see themselves as an extension of the prosecution, and nearly all trials end in conviction. The target can either capitulate or go to prison — losing the assets either way.

None of this was conducive to the kind of entrepreneurship that could add value to the Russian economy. Private investment suffered as the government’s actions made a mockery of property rights. The state’s share of the economy nearly doubled, to as much as 45 percent — prompting the International Monetary Fund in 2007 to question whether “the state was the best steward” of assets, given that “the poor performance of the state-controlled portion of the energy sector stands in stark contrast to the long-term performance of the privately controlled part.”

It didn’t help that the West rejected Putin’s early efforts to forge a friendship. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, he went against the advice of his own military to approve a U.S. presence along Russia’s southern borders. Yet the obvious quid pro quo — a welcome into the global economic community, even the World Trade Organization — never came. On the contrary, the U.S. imposed steel tariffs that contradicted its free-trade rhetoric. This undermined the West as a model and left Putin all the more dependent on the support of elites at home.

Crisis and mobilization: 2008 — 2018

A window of opportunity seemed to open in May 2008, when Putin temporarily handed the presidency to his prime minister, Dmitry Medvedev, who was then perceived as a relatively liberal reformer. Medvedev unveiled an ambitious modernization program to rebalance the Russian economy away from oil toward technology, and pledged to “protect civil and economic freedoms” and “fight for a true respect of the law.”

It wasn’t to be. Within months, the global financial crisis started to erode the previous eight years’ gains, forcing the government into damage-control mode. The state’s role in the economy grew further as it bailed out some companies and the recession wiped out others. Spending aimed at mollifying people and the military weakened government finances, ultimately leading Kudrin to resign.

Suddenly, Putin’s bargain of prosperity for freedom didn’t look so good. The ruling party barely maintained its majority in the 2011 parliamentary elections, and thousands took to the streets to protest widespread fraud. The demonstrations grew exponentially ahead of the 2012 presidential vote, which Medvedev ceded to Putin in advance.

The scale of the protests caught the Kremlin by surprise, prompting a crackdown reminiscent of the Soviet police state. Police beat and jailed peaceful protesters, and selectively pressed criminal charges. New rules made legal public gatherings all but impossible. A court convicted opposition leader Alexei Navalny of stealing lumber — a charge that the European Court of Human Rights later found to be baseless.

Putin diverted attention from the faltering economy by attacking internal and external enemies. The punk-performance group Pussy Riot was sentenced to two years in a prison camp, essentially for using vulgar language in a church. Kremlin-loyal politicians mounted a campaign against homosexuality, ultimately passing a law banning "propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships." After Putin blamed the protests on foreign agitators, parliament passed another law requiring nonprofits that received donations from abroad to register as foreign agents.

Meanwhile, Putin rewarded the elite by engaging in precisely the kind of waste and corruption that Navalny had made his name uncovering. One notable example was the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, by far the most expensive ever at a cost exceeding $50 billion. Another was Gazprom, which, as one Russian analyst famously noted, tends to engage in huge projects that primarily benefit well-connected contractors, rather than the state as its controlling shareholder. In both cases, multi-billion-dollar contracts went to people close to the president, such as Gennady Timchenko and childhood friend Arkady Rotenberg.

Show trials and scapegoats weren’t enough to keep the people distracted: Putin’s approval rating fell to the low 60s. Something bigger was required. It came days after the Sochi Olympics ended, when Putin initiated a foreign adventure that would transform Russia’s internal politics and relations with the West: the annexation of Crimea. The move demonstrated the military's capabilities and galvanized Russians, who had fond memories of vacations on the peninsula in the Black Sea.

In one fell swoop, Putin rewrote the social compact: Instead of prosperity, Russians would get national pride in return for their loyalty. Western sanctions and support for Ukraine only helped to drive home his argument: The West was out to get Russia. A mobilization psychology set in. Anyone who didn’t go along was an enemy of the people. By June 2014, Putin's rating had shot back up to 86 percent.

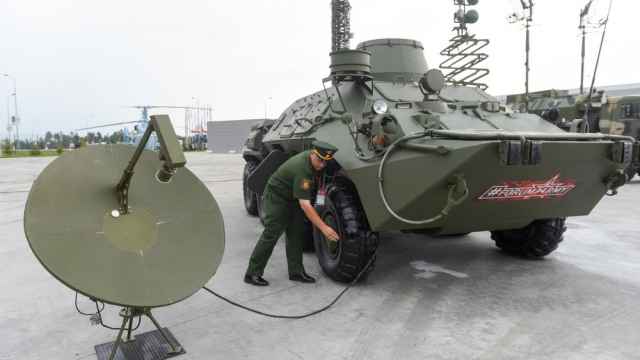

Sensing the zeitgeist, Russia’s security services intensified their hybrid war with the West. They offered support to far-right parties in Europe, seeking to sow discord and slow the European Union’s advance toward Russia’s borders. And in a gambit that is still having repercussions globally, they engaged in a U.S. operation — including hacked Democratic Party emails and a social-media disinformation campaign — that may have tilted the 2016 election in favor of President Donald Trump.

What's next

Putin’s efforts to confound the West, crush the opposition and build a loyal elite have brought Russia to an impasse. Western sanctions are finally starting to bite, starving the country of foreign technology and stirring dissatisfaction among some of his most wealthy backers. Private investment remains meager, because whatever people build can be taken away. A plan to raise the pension age has sparked nationwide protests, as Russians reasonably ask why they should wait for their money when Putin’s friends are getting rich on state contracts. Although prudent fiscal and monetary management helped the country get through a recent recession, it can’t improve the bleak outlook: With annualized growth forecast at less than 2 percent, Russia’s economy is set to fall behind the rest of the developing world.

What to do? Putin could double down on mobilization, but there’s no obvious way to repeat the success of the Crimean land grab. He could pursue closer cooperation with China, but the two countries have conflicting interests in Central Asia and a history of mistrust. He could pivot back toward liberal economic policies and better relations with the West, but that would be an uphill battle given Russia’s image as an international poisoner and election-meddler — not to mention the unpredictability of the Trump administration.

Putin understands that he needs an economic breakthrough. To that end, he has turned again to Kudrin, whose Center for Strategic Research has produced a wish list reminiscent of 2008: improve human capital through investments in education and health care; eliminate barriers to entrepreneurship; leapfrog ahead in the application of new technologies; double Russia’s non-oil exports; make government more efficient and service-oriented; and invest in transportation and urban infrastructure. Most important, it stresses that “economic success will be impossible” unless Russia establishes a rule of law, in part by making courts truly independent.

Putin has adopted much of the program, placing special emphasis on longevity, infrastructure and technological advancement. He has developed a cadre of mostly younger technocrats who are working to modernize the country, particularly its leading cities — an effort that was on display during the 2018 World Cup. Moscow is the model for the new urbanism, with dazzling new subway stations, world-class parks, and dynamic restaurant and retail sectors. There’s even a startup incubator complete with prototyping labs, a cutting-edge graduate school, international partners and hundreds of companies working on everything from payment systems to flying motorcycles.

Yet the essential ingredient — the protections needed for business and civil society to flourish — will be the hardest for Putin to provide. If laws were fair and courts made decisions on the merits, the government wouldn’t be able to imprison its opponents, and the Kremlin elite wouldn’t be able to grab assets at will. He would have to act against the interests of his allies, dismantling the structure of control on which his authority rests. The result could be a return to chaos.

If Putin can’t establish a rule of law, how does Russia get from where it is to a brighter future? His subversion of elections has left the country with no mechanism for a peaceful transfer of power. Revolution is not a solution: Not enough middle-class Muscovites will risk their lives to topple Putin’s regime, and the people who would aren’t likely to install a better one. Some Russians hope that an enlightened faction within the elite can take over. But it would have to prevail over other factions: Imagine various well-financed forces, all sophisticated in the use of media to stir people’s emotions, battling for control of the country. And an increasingly divided and identity-challenged West is unable to offer much help or inspiration.

From today’s perspective, it’s hard to see how Putin’s long reign can end well. That said, a lot can change before his current term ends in 2024. If anything, Russia knows how to produce surprises. May they be good ones.

Mark Whitehouse writes editorials on global economics and finance for Bloomberg Opinion. He covered economics for the Wall Street Journal and served as deputy bureau chief in London. He was founding managing editor of Vedomosti, a Russian-language business daily. The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.