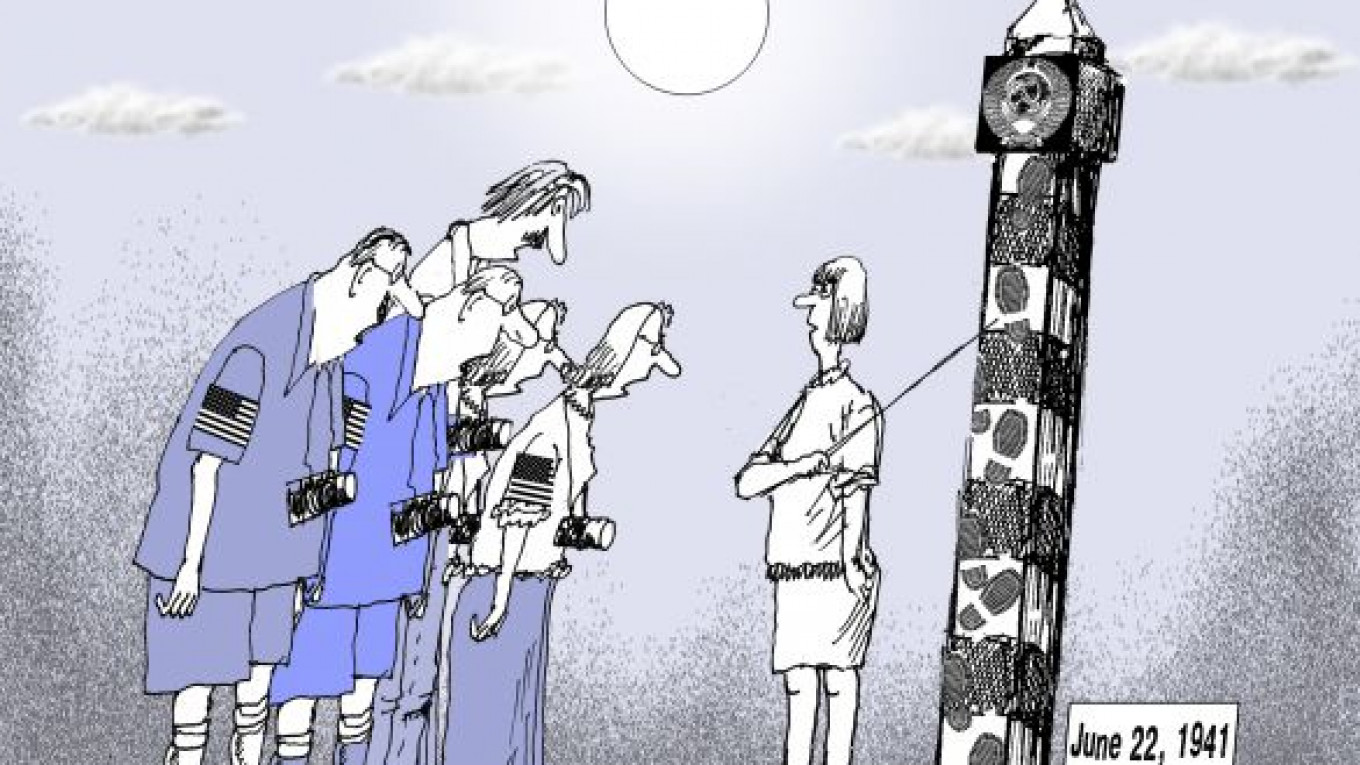

As every man, woman, girl and boy in Russia knows, Germany attacked the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 — exactly 70 years ago. The Great Patriotic War, as it is called in Russia, divided history for Russians into “before the war” and “after the war.” Yet in the West, it remains largely an “Unknown War,” borrowing the title of a Soviet documentary filmed intended for Western audiences in the final perestroika years under Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Influenced by the Cold War, in which ideology played a significant part, textbooks in the West left the Soviet Union’s role in the war as something of a blank page. It was hard to acknowledge that the totalitarian Soviet Union played the key role in crushing Nazism.

Yet this can hardly be contested. Eighty-five percent of German manpower and three-quarters of Germany’s tanks, planes and artillery were destroyed on the Eastern Front. The Soviet Union won, but its losses exceeded those of Germany by several times. Though exact figures are still unknown, from 27 million to 37 million Soviet citizens perished in the war, including more than 20 million civilians. Of all men born in the Soviet Union between 1921 and 1923, only 3 percent survived. The devastating demographic consequences of the war — the large gap in the number of men and women in the country — remained for 50 years.

Those who survived felt proud just because they were men. They did not have to prove their manhood; they were revered and cherished just because of their gender. It was mostly women who remained to lift the country from ruins and raise their families. They also did not have to prove anything; they had long proven that were able to do everything on their own. It also should not be forgotten that 500,000 Soviet women served in combat during the war.

World War II firmly ingrained the perception that war is disaster. Unlike in the United States, war is not a gallant, dashing endeavor for Russians, nor is it a march to a trumpet or adventure. It is a mass catastrophe. Almost every family in the country lost someone at the front. For generations after the war, one of the most common toasts at family parties was, “Let there be no war.”

Although the Soviet Union produced en masse the world’s best tank, the T-34, and the world’s first reactive artillery system, the Katyusha, most Russians believe that it was not military equipment but the readiness of soldiers to die that was the decisive factor on the battlefield.

As children of the postwar decade, we were raised on stories of heroic deeds, sacrifice, mass killings and Nazi torture. We listened to songs about the dead and, decades later, taught our children to sing them as well. Children and teenagers were among the heroes. No one ever investigated what happened to our psyches when we read about how they killed enemies and blew up rail tracks under Nazi transports, how they were tortured, maimed, crucified and thrown alive into mines. War veterans came to our schools to recount their experiences.

When I was 5 at summer camp, I heard a story of a former pilot who said he had stopped crying very early in the war — when he ran off to the front. I was determined that I would stop crying, too.

Unlike the “unjust” wars that it hid from the population — the Finnish war of 1939 and the Afghan war of 1979 to 1988 — the Soviet government did not have to hide the Great Patriotic War. Yet many facts about the war were not revealed for many years. New research is still appearing, including the excellent weekly program “The Cost of Victory” on Ekho Moskvy radio.

Even television programs about June 22, which often cause tears (despite my pledge), reveal new facts. For example, there are still about 600,000 soldiers from the Stalingrad battlefield alone who haven’t been buried. One million Soviet citizens collaborated with the Germans. Female pilots who flew wooden PO-2 light bombers could take little charge on board because of the small weight capacity of the aircraft and thus had to do up to eight raids per night — each time crossing frontline anti-aircraft artillery systems. They were not given parachutes because the Soviet command did not want them to be captured by the enemy.

Although many would argue otherwise, I believe that history is not subjective. We can collect piece by piece the picture of what really happened in the war, and I want people to know as much as possible.

When I taught in the United States, I used to tell my students ahead of time that one of the questions on the exam would be, “When did World War II start?” Still, half of them did not give the correct date of Sept. 1, 1939. I was also surprised to find that my fellow professors did not know that several million Soviet soldiers and civilians perished in German concentration and labor camps and that there were Soviet prisoners, beside Soviet Jews, in Buchenwald and Auschwitz.

When the 50th anniversary of the Normandy landing was celebrated in 1994, the main U.S. weekly magazines in their special issues did not once mention the Soviet Union. After this, I decided to put together a group of students of various nationalities and accompany them to various countries to work with archival documents to put together a real, multi-faceted history. The archives in Russia, unfortunately, have not been made more accessible since, but there is still much to uncover. And the more time passes since the war, the more urgent this task becomes.

Natalia Bubnova is deputy director of the Carnegie Moscow Center.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.