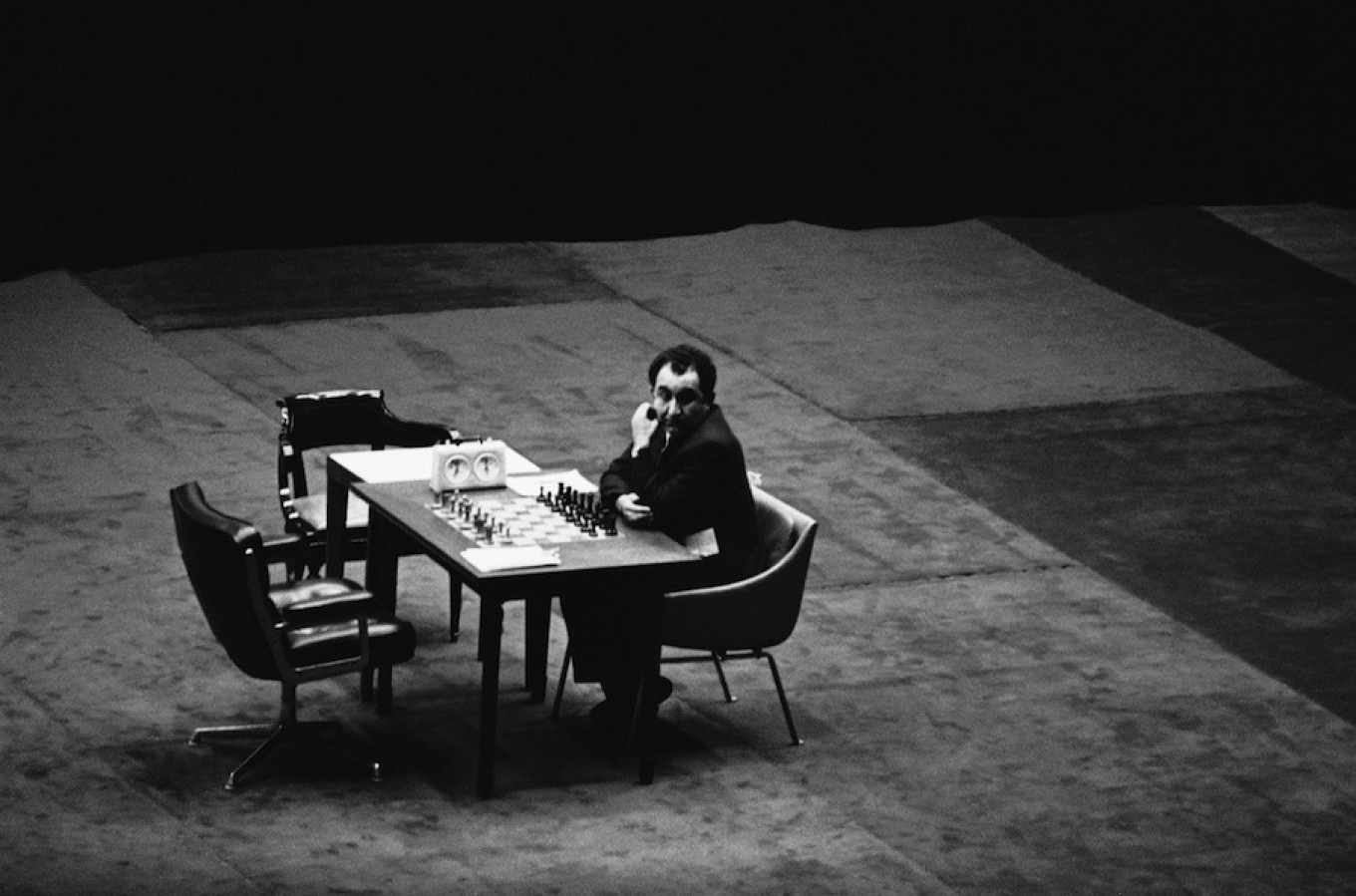

With only minutes left, Sergei Karyakin seemed lost in thought, much to some people’s frustration. “Why is he stopping to think right now?” an exasperated TV commentator asked, questioning the Russian’s slow play as the clock ticked down.

Many argue it was exactly that sangfroid disposition that propelled Karyakin to become the youngest grandmaster in history at age 12, and on to the World Chess finals in New York in the first place.

But in the end it wasn’t enough. With a quick and final sweep, Norway’s Magnus Carlsen sacrificed his queen to win the match and defend his world title after a three-week epic standoff that has put chess back on the map for the first time since the height of the Cold War.

It is as close as Russia has come to winning the world championship in a

decade and for weeks the prospect of “returning the crown” became nothing short of a national obsession, with Russians of different ages reminiscing about the glory days

when Soviet chess players dominated the world stage. A week after losing the final, for Karyakin the dream is still very much alive.

“It is important to bring back the crown to Russia,” Karyakin, 26, told The Moscow Times in a five-star hotel in central Moscow. “I’m going to dedicate all my efforts to making sure it happens.”

The Soviet School

While most fans associate chess with Soviet times, the board game first gained popularity in Tsarist Russia.

“Around 1890, the Russian Mikhail Chigorin came as close to defeating the then holder of the world title, the American Wilhelm Steinitz, as Karyakin was to beating Carlsen,” says Bernard Cafferty, a British chess master and author. More famously, the iconic Russian poet Alexander Pushkin was also a supporter of the game. In a letter to his wife, Pushkin thanked her for taking up the sport, saying: “It is indispensable to any orderly household. I’ll explain later.” (Sadly, he never did.)

It was the Bolsheviks, however, who made the hobby a matter of state. Early promotion of the sport was led by revolutionary Nikolai Krylenko, and no less than Lenin himself. Soon, matters of chess were as much ideology as sport, with players transformed into members of so-called Soviet “chess shock brigades.”

For

the Soviet leadership, chess served multiple functions, says Andrew Soltis, a

U.S. grandmaster and author of a book on Soviet chess. “It was seen as a very

cheap form of mass entertainment and a means, like ballet, of demonstrating

Soviet cultural supremacy,” he says. It was also of pragmatic use, as a way of reducing illiteracy among Red Army recruits.

Opinions vary as to whether there is a distinct “Soviet” school of chess, uniting big stars such as Mikhail Botvinnik, Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov. If anything, such a school was characterized by a highly professional attitude toward the game, and an aggressive playing style, says Soltis. But that chess became a central propaganda tool is indisputable.

“Chess was one of the very few international activities in which the Soviet Union vied with the West in the decade after 1945,” says Cafferty. At the same time, many of the Soviet stars, such as the Estonian Paul Keres or the Armenian Tigran Petrosyan were not, in fact, ethnic Russians.

Soviet domination over world chess lasted until the 1960s, with the emergence of two Western rivals — Danish player Dane Larsen and the American Robert Fischer who, in 1972, beat the Soviet world champion Boris Spassky. It was a humiliation for the Soviets, and “moved international chess into a new historical phase,” says Cafferty.

Meanwhile, cracks in ideological unity at home spilled over onto the chessboard. In 1984, the internal rifts were on display for the world to see in a tense standoff between the two Soviet rivals Kasparov, an Armenian Jew who had worked his way up the ranks, and Karpov, an ethnic Russian and clear favorite of the Soviet elite. Many saw Kasparov’s eventual, dramatic win in 1985 as a harbinger of the Soviet regime’s decline.

When the Soviet Union eventually crumbled in the 1990s, the chess scene imploded with it. “Chess clubs disappeared, coaches dispersed and chess players took up business instead,” says Sergei Shipov, a prominent chess commentator. Russia never fully recovered from the blow.

Political Charge

With the country failing to make its mark with more popular sports, such as

football, Russians have become hungry for chess greatness once more. The

country still produces strong chess players, such as Vladimir Kramnik, who was

world champion until 2007, and now Karyakin. Even though Karyakin was always

the underdog in the final, ranking ninth in the world at the start of the

tournament (and moving to sixth place after the tournament), domestically it was seen as a big success.

“The fact that a Russian chess player has made the top two is a huge achievement that Russian footballers can only dream about for another fifty years,” says Shipov.

Meanwhile, chess is regaining some of its Soviet-era charge. As in the old days, the sport is a place to play out political rivalries. “One way of showing off is to jump higher or run faster. But if you show you’re more intelligent — that has has a lot more prestige,” says Shipov.

Karyakin seems to have embraced the role of political ambassador for Putin’s Russia. Born and raised in Crimea, he competed under the Ukrainian flag for much of his early career. But in 2009, he was granted Russian citizenship, and appears to have never lost his gratitude. Holiday pictures from Crimea shared on social media show him wearing a T-shirt with Putin’s portrait and the words “We don’t abandon our own!” A picture of Karyakin alongside the Russian president is pinned to the top of his Twitter account.

Not surprisingly, he can count those at the highest level of Russian government among his fans. Putin’s spokesman

Dmitry Peskov flew out to New York to attend the final and Karyakin, a believer, recently told an interviewer on Russian state television that the head of the Russian Orthodox Church Patriarch Kirill was personally rooting for him.

The possibility that his enthusiastic support for the Kremlin and the annexation of Crimea could cost him some Western fans leaves him unfazed. “I have a right to express my opinion,” he says. “If that offends anyone, there’s nothing I can do. My views are not negotiable.”

God’s Mistakes

Despite the nationwide nostalgia, and the appearance of a possible future world champion, a return to the Soviet days of chess glory is unlikely.

The Kremlin’s weak spot for chess is not enough to compensate for the fact that, under capitalism, the rules of the game have changed. Chess has to compete with other sports such as hockey and football, which attract more viewers and more investment. Meanwhile, Russia’s rivals have gotten stronger, not infrequently employing Russian coaches to share the secret of the trade. Karyakin’s rival, Carlsen, was, for example trained by Kasparov for years.

Success is now largely down to individual players. “The biggest stars are God’s 'mistakes', it is pure coincidence,” says Shipov. “No one can understand how Carlsen emerged from Norway, a country with no chess tradition.”

While there are several Russians in the world chess elite, it is by no means guaranteed that a Russian will be sitting across from Carlsen in 2018, when the title is once more up for grabs. “There must be sore heads in the Moscow chess hierarchy wondering how to back any future great hope of Mother Russia,” says Cafferty.

Meanwhile,

Karyakin is giving it his all. His

regime involves punishing workouts — he lost 8 kilograms in the six months

ahead of the world championship — and a diet of almost no sugar on the

recommendation of doctors, he said.

Some media reports have also claimed Karyakin has a superstitious attachment to the color blue, wearing blue sweaters and blazers during matches. Asked about it, Karyakin merely looks stunned that such a rumor could exist about someone who has honed his rational mind.

“You’d better ask my wife about that,” he laughs. “To be honest, I have no clue what color my clothes are.”

The reincarnate of Russia’s long chess tradition is also just a man, after all.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.