It was the middle of the night when a group of Spanish police came crashing into the Levashovs’ vacation apartment in Barcelona.

“They broke the door down… and forced us onto the floor in front of our four-year-old child,” Mariya Levashova told the Kremlin-controlled RT television network in an interview given shortly afterward.

Mariya’s husband, Pyotr Levashov, is now in a Spanish prison facing extradition to the United States on hacking charges. The U.S. maintains he is a spamming kingpin living a luxurious life in St. Petersburg. But Levashova says her husband is just an average computer programmer.

For many years, the U.S. has hunted Russian hackers accused of committing cyber crimes, targeting them with extradition requests when they leave the relatively safe confines of the former Soviet Union. But the game of cat and mouse took on a different dimension following alleged Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The arrest of Levashov in April and at least two other similar cases appear to be the result of a stepped-up effort by U.S. law enforcement.

Russian officials have repeatedly denied charges of meddling, and accuse U.S. authorities of kidnapping its citizens. In at least one instance, Russia has filed a counter-extradition request in a bid to nullify a move by the U.S.

The stakes of the hunt are high. Russian hackers who the U.S. succeeds in extraditing can expect long prison sentences if found guilty. Earlier this year, a Seattle court convicted Roman Seleznev, a Russian hacker, and son of a Duma deputy, to 27 years in prison. He was handed over to the U.S. by police while on holiday in the Maldives.

In a statement read out by his lawyer after the trial, 32-year old Seleznev, who has health problems, said he had been handed the equivalent of a “death sentence.”

The hunters

One of the key challenges for U.S. investigators is linking a hacker’s digital footprints to a real person — and then proving the connection. Cyber-criminals often use dozens of online nicknames to throw investigators off the trail. According to the U.S. magazine Wired, Levashov was caught when he committed a basic error: he used the same credentials to log into his criminal ventures as he did to ordinary sites and applications like iTunes.

Another challenge police face is coordinating sprawling investigations, which can involve criminals all over the world. Cyber-crooks work in closely-knit online units, and not necessarily in the same country. Such groups involve technical specialists and managers, as well as mules responsible for cashing-out after successful cyber-heists. In December, the FBI was one of 30 law enforcement bodies involved in the world’s largest ever cyber-takedown, destroying an online crime platform known as Avalanche. At the end of the four-year investigation, police carried out 5 arrests, seized 39 web servers and removed more than 830,000 web domains.

At the same time as Levashov’s arrest in Spain in April, U.S. agents were working to dismantle the Kelihos botnet, a global network of infected computers. Kelihos was reportedly used to harvest login information, blast out millions of spam messages, implant malware and artificially elevate the price of certain stocks (so-called pump and dump schemes). The U.S. Department of Justice says Levashov had been running Kelihos since 2010.

“The ability of botnets like Kelihos to be weaponized quickly for vast and varied types of harm is a dangerous and deep threat to all Americans,” U.S. Acting Assistant Attorney General Kenneth Blanco said in a statement announcing the arrest.

Alongside FBI agents, cyber-security firm Crowdstrike was closely involved in the Kelihos operation. The firm also played a prominent role in publicizing what it says are the Russian fingerprints on hacks designed to sway the U.S. elections.

Media reports have identified FBI Special Agent Elliott Peterson as a key figure in pursuing the case against Levashov and Kelihos.

A veteran of the FBI’s crack cyber force based out of Pittsburgh, Peterson has been involved in a number of high-profile Russian cyber-crime cases. He was part of a team that dismantled the GameOver Zeus malware network, which was designed to steal user credentials.

The network was supposedly run by Yevgeny Bogachyov, a Russian programmer who masterminded the alleged theft of hundreds of millions of dollars worldwide. Bogachyov has been linked to Russian cyber-intelligence gathering operations in Ukraine, Georgia, and Turkey. Despite a $3 million FBI bounty on his head, the programmer is reported to be living openly in the Russian Black Sea resort town of Anapa.

The hunted

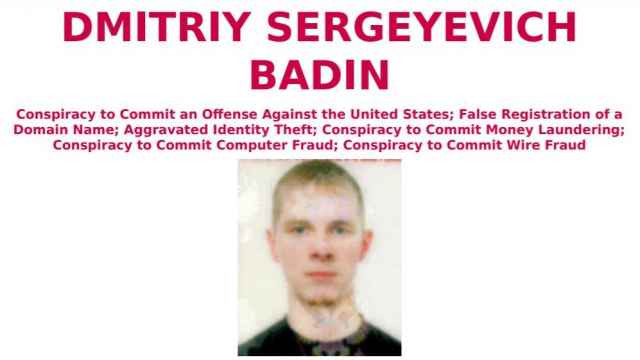

There have been at least three recent arrests of men the U.S. claim are Russian hackers. In addition to Levashov, they include Yevgeny Nikulin, 29, a Moscow resident reportedly accused of password hacks on LinkedIn and Dropbox and arrested in Prague in October. Stanislav Lisov, a 32-year-old from the southern Russian city of Taganrog, was detained in Spain in January for allegedly developing and using the computer virus NeverQuest.

U.S. law enforcement does not explicitly link any of these three cases to election hacking, but both Nikulin and Lisov have claimed they are being pressured to admit to such crimes.

In a letter written from prison, Nikulin said that an FBI agent had raised election hacking with him during an interrogation. Lisov told his wife, Darya Lisova, by telephone on a program broadcast in February by RT that he was asked if he had “hacked the Pentagon, FBI, and CIA.” There is no way to confirm either man’s account.

Little was publicly known about Nikulin or Lisov before their arrests. But both men appear to have led very comfortable lives. A now-disabled Instagram account run by Nikulin shows he socialized with the children of Russia’s political elite, including the daughter of Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, and was a lover of expensive sports cars. Despite living in the small town of Taganrog, near Russia’s border with Ukraine, Lisov’s social media accounts show that he spent a lot of time abroad, with frequent holidays including trips to the Maldives.

Levashov has a more prominent public profile. The European anti-spam organization Spamhaus describes Levashov as “one of the longest operating criminal spam-lords on the internet.” In his 2014 book Spam Nation, U.S. cyber-security journalist Brian Krebs links Levashov, via the online pseudonym Peter Severa, to the Waledec spam botnet, which, at its peak, blasted out 1.5 billion messages a day.

Hackers and the FSB

There is speculation that the timing of the arrests of Levashov, Lisov and Nikulin means that they have been caught up in a broad cyber-struggle between Washington and Moscow.

Russian security services have long maintained close ties to the cyber-underworld. The FSB is said to prefer informal agents, which can be easily disowned, and a complex web of intermediaries of hackers, cyber-security experts and rogue programmers. Russian police, meanwhile, follow a policy of turning a blind eye to cyber-criminals who work outside of Russia and cooperate with the intelligence services.

“It’s not that difficult to make these connections: the FSB know where these guys are and they know where they can find them when they need to,” says Nigel Inkster, a former British intelligence officer and the director of Future Conflict and Cyber Security at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London.

In a 2017 indictment relating to the theft of 500 million Yahoo email accounts in 2014, U.S. prosecutors identified two FSB officers, Dmitry Dokuchaev and Igor Sushchin, accusing them of paying hackers for their work. It was the most public demonstration of links between the Russian hacking community and security services.

33-year-old Dokuchaev, currently under arrest in Russia on separate treason charges, appears to have worked as a hacker before joining the FSB.

In a 2004 interview with the Russian newspaper Vedomosti, a hacker called Forb boasted of making money from credit-card fraud and breaking into U.S. government websites. Seven years later, the Russian-language Hacker magazine identified Dokuchaev as Forb.

Blackmail apparently often also plays a role in recruitment. Another Russian programmer, Dmitry Artimovich, who was jailed in 2013 for hacking offenses, said in an interview that the FSB had made repeated attempts to coopt him. The first time, he said, was via his cellmate when he was in prison awaiting trial. According to Artimovich, the man told him that if he cooperated he would be released immediately—a deal he refused. Since being released, Artimovich said he has been asked dozens of times to carry out hacking operations. Most of these approaches are made via social media. He says the offers are designed to tempt him to break the law and become vulnerable to FSB pressure.

The exposure of a hacking group called Shaltai Boltai (“Humpty Dumpty”) earlier this year has also highlighted the links between Russia’s security services and cyber-crime. Shaltai Boltai blackmailed top Russian officials after stealing personal information and leaking details to the press if payments were not made. Alexander Glazastikov, a member of the group who escaped arrest, said earlier this year they would give FSB officers material from hacked email accounts in exchange for protection.

There is no public evidence that the recent arrests are connected with espionage operations or attempts to influence the outcome of the U.S. presidential election. But with such complicated interdependencies present between Russia’s spy agencies and its hackers, the thought that they might know something about such operations must have at least have crossed the minds of FBI agents.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.