When Konstantin Goldman visited Moscow’s Red Square on Sunday, he took with him a book: Leo Tolstoy’s “War and Peace.” He held the novel as he was photographed next to a World War II memorial — in particular, a stone marked in honor of the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv.

The effect was immediate. Goldman was detained for “violating protest laws” and escorted to a nearby police station.

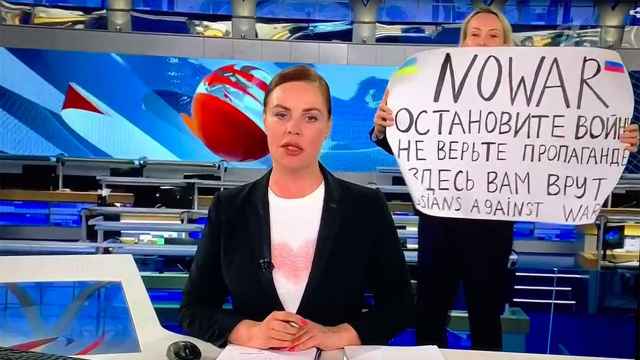

At least 214 people were detained for staging anti-war protests in 18 Russian cities over the weekend, according to the independent police-monitoring website OVD-Info. Most of the actions were single-person pickets, the only form of protest that doesn’t require local authorities’ approval in advance.

“This is some kind of enormous joke that we, to our misfortune, are living in,” Alexandra Bayeva, who heads OVD-Info’s legal department, told The New York Times.

Under laws signed by President Vladimir Putin soon after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, anyone discrediting or spreading “knowingly false information” about the military faces up to 15 years in jail.

In the weeks that have followed, officials have encouraged the creation of “self-cleansing of society” leading to the appearance of lists of “traitors and enemies” — Russians who oppose the war — online. Elsewhere, websites have urged Russians to report on “pests” to public officials.

Some citizens have enthusiastically taken up the call. In Russia’s republic of Buryatia, 6,000 kilometers east of Moscow, archery coach Valery Yakovlev was reported to the police for tearing down a large letter Z that had been fixed to his school’s entrance.

The letter Z, which first appeared on the sides of Russian tanks massed at Ukraine’s border, has come to symbolize support for what the Kremlin calls a “special military operation.”

Yakovlev, 64, was secretly recorded by the janitor fuming against the war in Ukraine, according to the Lyudi Baikala news website. He was later accused of discrediting the Russian armed forces, and fined a total of 90,000 rubles (approx. $1,000) during three court rulings last week.

Yakovlev told the court that he believed “kids [should be] outside politics,” but school principal Inessa Karpukova defended her decision to turn him into the police.

“Putin said that any extremist activities against the Russian army and military operations should be suppressed,” she said, according to Baikal Journal. “That’s why we took those measures.”

In a similar case, Yevgeny Fokin, a civically engaged 10th-grader in Russia’s third-largest city of Novosibirsk, faces up to three years in prison after sharing a comment on messaging app Telegram, local media reported Saturday. While the content of the post is not known, it was described by officials as spreading “false information” about the Russian military.

Novosibirsk municipal deputy Svetlana Kaverzina, who commented on Fokin’s case last week, blamed the “blossoming” Soviet-era practice of turning in fellow citizens for dissenting views.

“Our mighty army, it turns out, is very easily discredited by a mere schoolboy,” she wrote on Telegram. “The state has to use its entire apparatus to put pressure on a schoolchild.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.