Western sanctions and an economic crisis resulting from the invasion of Ukraine are hindering Russia’s HIV/AIDS charities, activists and campaigners say, in what risks worsening an already grave epidemic.

“We can’t buy many of the things that we are used to buying,” the head of one regional AIDS charity told The Moscow Times. “The price of condoms has increased five times… [and] tests for HIV that we could buy for 200 rubles ($2) now cost 1,500 rubles ($18).”

About 1% of Russia’s population of 146 million is currently HIV positive, and infection rates are growing faster than in most Western countries.

With difficulties obtaining drugs, tests and contraceptives, AIDS deaths in Russia look set to rise.

Russian charities working with those affected by HIV/AIDS sufferers have traditionally received significant financial support from international funds, in particular the U.K.-based Elton John AIDS Foundation (EJAF) and the World Bank-financed Global Fund.

But the Western sanctions on Russia and subsequent difficulties with international money transfers following Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine have caused logistics chaos and raised questions about the future of foreign funding, charity workers say.

“We used to receive funds from the Elton John Fund once every half a year… but because the situation is unclear at the moment we receive them once a month,” said the head of an AIDS support charity based in the Urals. His charity receives large amounts from the EJAF and Global Fund.

A spokesperson for the EJAF declined to comment on the future of the organization’s work in Russia, citing concerns for staff safety.

“It will get worse, no question. I think that it’s very scary, all of this, because I’ve lived and worked in this sphere for a long time, and I see that clearly there’s a problem with an interruption of drug supplies,” said one charity worker who began working with HIV patients in the final years of the Soviet Union and is now the head of an AIDS support organization operating near Moscow.

HIV express test kits, including imported OraQuick and Abbott kits used by this campaigner’s organization, provide quick and confidential HIV screening and avoid more time-consuming — and expensive — blood tests.

“I think there will be problems with tests with reactants, because these are all imported. We purchase them from Japan, Korea and the United States,” the charity worker said.

Many fear there could be a repeat of patterns of behavior observed during the coronavirus lockdowns of 2020-2021.

“All the biggest production firms for furniture, cars, IKEA, materials etc. are exiting Russia and leaving behind unemployed people. And what do unemployed people do? They get stressed, stress equals alcohol, and alcohol leads to sex – sex without a condom. Or it’s drugs, which again leads to sex without a condom,” said a St. Petersburg-based AIDS activist.

The activist added that his AIDS work was facing problems because the organization he worked for had been designated a “foreign agent” by the Russian government. The “foreign agent” status does not prevent an organization from operating, but it increases bureaucratic requirements and complicates fundraising.

“Russia has started to recognize foreign agents again and has again started a witch hunt, and this will lead to very strict control of all kinds of finance,” he said.

In the face of the growing threat to foreign funding, some charities are seeking to shift priorities toward domestic money streams.

“Until now, all of our funding was from abroad. Even if it came from a Russian organization, all the same it was from a foreign donor,” said Victoria Dollen, the director of the AIDS Foundation East-West. “[But] a little while ago we came to the conclusion that we need to look at our balance for finance, and work more within the country and with the government.”

Dollen was also hopeful that businesses could also be recruited to help provide funding for struggling HIV/AIDS charities.

“The HIV problem is a demographic problem. If we get the right angle here, then competent, corporate business could be interested,” she said.

Most activists interviewed by The Moscow Times said Russia appeared to be on the threshold of a new HIV/AIDS crisis. HIV infection rates also tend to rise in times of uncertainty and economic crisis — and some predict Russia’s GDP will contract as much as 15% this year.

Unlike past economic crises, Russia is already in the grip of an HIV epidemic. There were 32,000 HIV-related deaths in Russia in 2020. Even before the outbreak of the war with Ukraine, demographers estimated that Russia’s HIV mortality could overtake the cancer mortality rate by 2030.

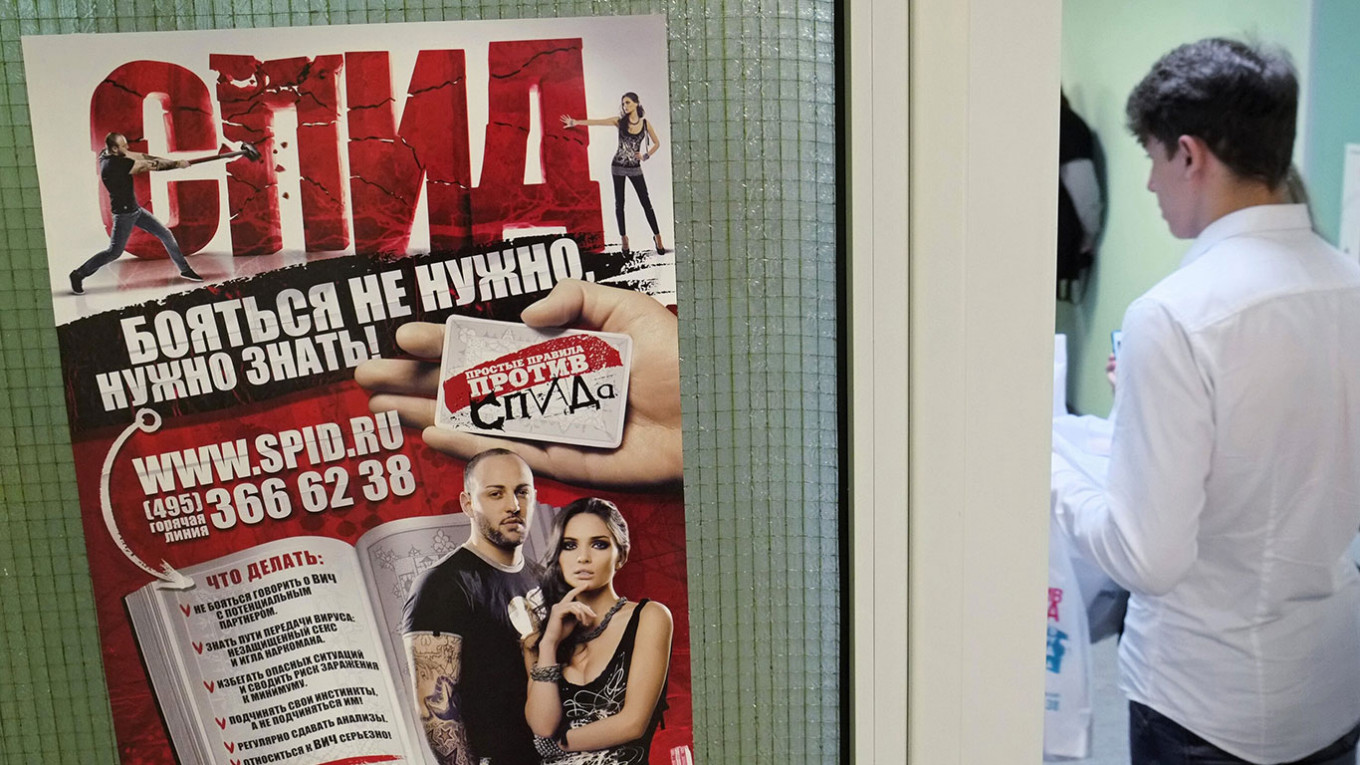

Nor is much help expected from the Russian government, which tends to focus on promoting “traditional values” over prophylactic measures, safe sex campaigns, education, and substitution therapy for drug addicts.

“We speak different languages,” said one St. Petersburg-based charity worker of how the government’s approach differs from that of activists. “They have their own way… For them everything is about documents and papers.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.