Russia’s Supreme Court on Tuesday ordered the shuttering of Memorial, Russia’s oldest human rights watchdog, for repeatedly violating the country’s foreign agent law.

The group's closure rounds out a year in which Russian authorities have cracked down on nearly all forms of dissent, from Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny's opposition groups to independent news outlets and rights organizations.

State prosecutors argued that the group systematically refused to label itself as a “foreign agent” on its website and other published materials as is required. Memorial has maintained that there was “no legal basis” for the case against it and called the law a tool to crack down on independent groups.

For Memorial’s supporters, the move to liquidate the organization is a hammer blow to Russia’s already beleaguered civil society, and to efforts to come to terms with the country’s traumatic 20th century.

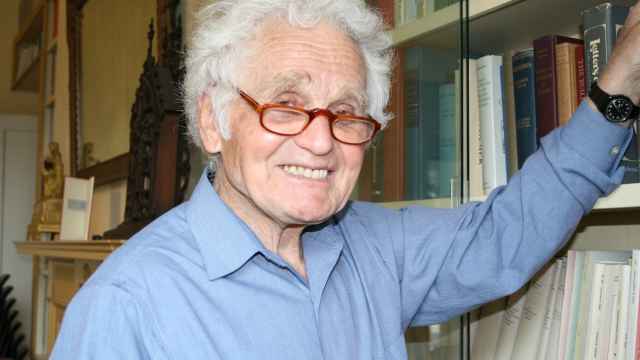

“Shutting down Memorial is worse than a crime,” Vyacheslav Igrunov, a Soviet-era dissident and founding member of the organization, told The Moscow Times.

“It’s a terrible mistake that will come back to bite the authorities.”

Exposing repressions

Founded in the twilight of the Soviet Union by nuclear physicist turned anti-communist dissident Andrei Sakharov, Memorial aimed to support human rights in contemporary Russia while highlighting historical abuses in the U.S.S.R.

As Mikhail Gorbachev’s reform program opened the door to discussions of Stalin-era repressions, Memorial took a leading role in publicizing many of the Soviet Union’s worst excesses, including the 1940 Katyn massacre of Polish prisoners of war.

In a joint statement last month, Gorbachev and Novaya Gazeta editor and 2021 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Dmitry Muratov warned against Memorial’s closure, saying the case has “caused anxiety and concern in the country, which we share.”

Among the countries of the former Soviet Union and wider communist bloc, the fate of Memorial — which investigated Soviet repressions against their citizens — has prompted unease.

Amid an earlier hearing in November, the presidents of Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia issued a joint statement condemning efforts to shut down the group.

A petition in support of the organization had been signed by over 138,000 people.

In the hours before the verdict was announced Tuesday, a group of around 200 Memorial supporters gathered outside the Supreme Court to show their support, despite the December cold.

For 23-year-old economics graduate student Artemy Korulko, Memorial’s fate was personal.

Korulko’s great-grandfather was shot as a Polish spy during Stalin’s 1937 purges, and Memorial had investigated his case upon its founding in the perestroika years.

“I’m here to register my opinion. Memorial has helped my family, and it’s my duty to return the favor now.”

As well-wishers outside the courtroom waited for the verdict, a string of supporters were arrested for mounting solitary pickets, eliciting shouts of support from the gathered crowd.

Memory wars

For some observers, it is Memorial’s work in the historical field that has placed it in the Kremlin’s crosshairs.

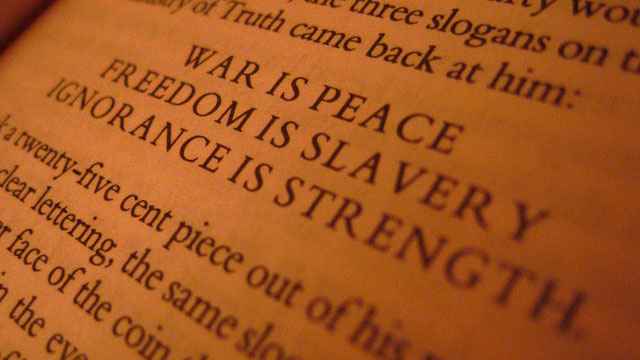

With President Vladimir Putin presiding over a limited rehabilitation of the Soviet past, including defending Josef Stalin’s wartime leadership and foreign policy, Memorial’s investigation of the totalitarian past has fallen out of official favor.

With Russia’s modern-day security services — the heirs to the Stalin-era NKVD secret police — widely thought to have the president’s ear, aspersions cast on their predecessor organizations can be politically perilous.

Ahead of the ruling, a state prosecutor argued in court argued that Memorial had blackened the Soviet Union's wartime legacy, asking, "Why do we, the offspring of victors, have to repent and be embarrassed, instead of being proud of our glorious past?"

“Memorial has become the primary opponent of the official position on history,” said Andrei Kolesnikov, an analyst at the Carnegie Moscow Center think tank.

“The authorities imagine that if you destroy the organization, you can destroy its narrative too.”

But as Russia’s post-Soviet political system took a more authoritarian turn, Memorial’s focus shifted toward exposing modern-day abuses.

The organization’s work documenting human rights abuses in war-torn Chechnya implicated the Russian army, Chechen separatists and the local pro-Russian regime of Ramzan Kadyrov in atrocities. The 2009 murder of Natalia Estemirova, a local Memorial representative, was widely seen as retaliation for the group’s work.

Meanwhile, Memorial helped set up OVD-Info, a Moscow-based service that provides legal assistance to those jailed at protest rallies, and which recently joined its parent organization in being designated a foreign agent.

For founder Igrunov, Memorial’s political work is likely what attracted the Kremlin’s ire amid a thoroughgoing crackdown on Russia’s opposition and civil society groups.

“The authorities have come to fear the things Memorial says,” he said. “This kind of work isn’t acceptable in Russia anymore.”

In 2014, Memorial became one of the first organizations targeted under Russia’s 2012 law on foreign agents, under which groups accused of receiving foreign money are obliged to make lengthy financial declarations and include the status on all materials they produce.

Though the charges filed against Memorial officially relate to the organization’s failure to label books sold at a Moscow event with the disclaimer required of “foreign agent” organizations, many of Memorial’s supporters suspect the charges are motivated by revenge for its human rights work.

The Meduza news website has reported that Memorial’s violations of the foreign agent law were reported by the local FSB office in Ingushetia, a small North Caucasus region with close ties to neighboring Chechnya.

'We'll start from scratch'

However, despite the bleak legal outlook, Memorial veterans insist that the organization — which is highly decentralized and includes more than 60 branches across Russia’s 85 regions — will continue to exist, in one form or another.

“In the worst-case scenario, we’ll start everything again from scratch,” said Elena Zhemkova, executive director of International Memorial, at a recent press conference.

“We’ll find the money all over again, and we’ll find the facilities all over again.”

However, recent actions against those cooperating with Memorial suggest the organization’s difficulties will not end with today’s ruling.

Over the weekend, Russian authorities blocked the website of OVD-Info for allegedly promoting “terrorism and extremism.”

In 2016, Yury Dmitriyev, a historian who worked with Memorial to investigate Stalin-era mass graves in Karelia, near the border with Finland, was arrested on charges of pedophilia.

His 2020 conviction and sentencing to 13 years in prison was seen by some commentators as a warning shot against those looking to unearth the dark side of the Soviet past, and a harbinger of what might yet be in store for them.

Only a day before Memorial was shuttered, 65-year-old Dmitriyev’s sentence was extended by two years.

For some of Memorial’s supporters gathered outside the Supreme Court, the organization’s closure reflected a repressive net being cast ever wider by the Russian authorities.

“There’s no logic to this case, it’s as though the courts are just acting out of habit now,” said economics student Korulko.

“The system can’t stop itself anymore.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.