Memorial, dissolved by Russia's Supreme Court on Tuesday, was the country's most respected human rights organization whose closure signals the tightening authoritarian tendencies under President Vladimir Putin.

The court ruling against Memorial International, the organization's central structure, seals a swift judicial process to shut down the group, which emerged as a hopeful symbol during Russia's chaotic transition to democracy in the early 1990s.

Memorial established itself as a key pillar in civil society by battling to preserve the memory of victims of Communist repressions and campaigning against rights violations linked to Russia's brutal wars in Chechnya and beyond.

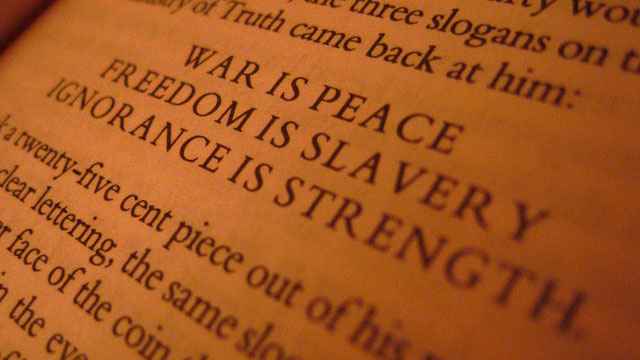

The group maintained a massive archive of Soviet-era crimes and questioned official narratives that glossed over horrors committed under Josef Stalin, but showed concern for contemporary rights abuses too by bringing legal cases against Russian mercenaries in Syria.

Rights activists in December asked Putin to intervene.

But the Russian leader told his human rights council that Memorial had been advocating on behalf of "terrorist and extremist organizations," clearly signaling his backing for its closure.

Memorial has been compiling a list of political prisoners who include members of banned religious groups like the Jehovah's Witnesses, and Putin's most prominent critic Alexei Navalny, whose political organizations were shut down this year.

In October, Memorial said the number of political prisoners in Russia had risen to 420 compared to 46 in 2015.

Memorial's closure comes amid an unprecedented crackdown on critical voices that intensified after authorities jailed Navalny in February. But the enormity of outlawing the country's most prominent rights group stands out even amid the current clampdown.

"The disappearance of Memorial in Russia will become a symbol of a deep moral fall and the definitive symbolic estrangement of the Russian man from the civilization of the 21st century," dozens of prominent Russian figures said in an open letter.

"The wounds, which have not healed over the 30 post-Soviet years, are bleeding again."

Memorial was founded in 1989 in the final years of Communist rule under Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

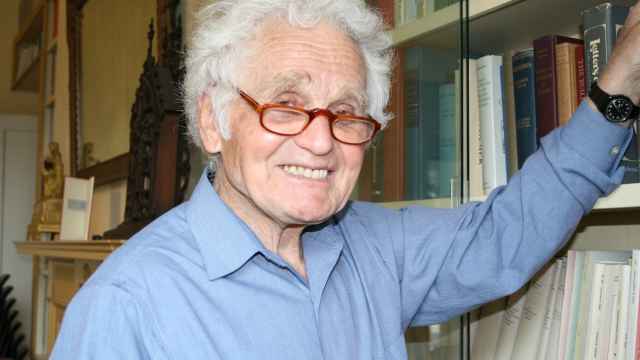

Its first chairman was the Nobel Prize-winning Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov.

The group, which was regularly cited as a potential Nobel Peace Prize winner, had been in the crosshairs of the Russian authorities for years.

The Memorial Human Rights Center was put on the government's register of "foreign agents" in 2015. Memorial International was added a year later.

The "foreign agents" label, which has dark Soviet-era connotations, requires individuals or groups to disclose sources of funding and mark all publications — including social media posts — with a tag.

Memorial has labeled claims it broke the law or backed terror and extremist groups as "absurd."

'Ever more repressive'

Memorial gained prominence for chronicling the victims of Communist repression — a painful subject that modern Russia has been reluctant to address — and investigating executions and kidnappings committed against civilians during Moscow's two wars to subdue Chechen separatists.

This year Memorial and several other groups released a report on Moscow's role in the Syria campaign and urged Russians to take responsibility for abuses in the war-torn country.

But Memorial's crusading work has come at huge personal cost to those involved.

Natalya Estemirova, one of the group's main employees in Chechnya who gained worldwide renown, was found dead in 2009 with gunshot wounds hours after she was seen being bundled into a car outside her home.

Another Memorial employee, Yury Dmitriyev, who spent decades locating mass graves in the northwestern region of Karelia, was jailed in 2020 on a controversial child sex charge.

Supporters insist the 65-year-old historian was targeted for his work.

On Monday, a Russian court handed him an additional two years in prison.

Irina Shcherbakova, a senior member of Memorial, said the Kremlin was sending a clear signal to the West by banning the group.

"We are doing whatever we feel like with civil society. We will put whoever we want behind bars. We will close down whoever we want," she said.

"The dictatorship is becoming ever more repressive."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.