The news of the largest prisoner exchange between the West and Russia since the Cold War brings hope. But we must keep in mind that the people freed are only a tiny fraction of the hundreds of political prisoners held in Russia. Furthermore, the deal might serve to embolden the Kremlin, which now knows it can easily take hostages to trade for captured spies and killers.

I am a journalist who has focused on Russia throughout my life. So the news of Evan Gershkovich’s arrest came as a huge shock on a visceral level. I was terrified, and I abandoned all plans to ever visit my beloved Moscow, as the illusion of safety the “foreign journalist” status once provided was definitively gone.

Now, as Evan and his fellow reporter Alsu Kurmasheva are safe and sound and on their way back to the U.S., I feel such deep relief. I feel grateful to their families, Western diplomats and Russian civil society in the West who have tirelessly pushed for this exchange to happen.

This exchange feels like a massive boost to the possibility of a future democratic Russia and a win for human rights. The people freed are leaders, activists, journalists and artists, some of the best and brightest in Russian civil society — although so many equally talented people remain in Russia. Their freedom will have ripple effects beyond the joy of their families as they create, lead and write toward the goal of a more just Russia and world.

But as I think about it more deeply, I become increasingly pessimistic. It is important to note that the exchanged 16 are but a tiny fraction of Russia’s political prisoner population. My organization, OVD-Info, counts at least 1,289 dissidents in Russian prisons. At least 10 have died in custody.

And while the West is getting political prisoners and leaders, the Kremlin is welcoming home killers and spies. Returning to Russia are people like Vadim Krasikov, who was jailed in Germany for shooting an exiled Chechen rebel commander in Berlin. Krasikov is a bona fide assassin, who had started his killing spree at least as early as 2007.

Finally, we must remember that the Kremlin chose to kill Alexei Navalny rather than to exchange him, as the Anti-Corruption Foundation’s Maria Pevchikh said after Navalny’s death.

This exchange might become a harbinger of worse to come. The Kremlin could become emboldened, seeing that it has found a way to get its people out of the West, no matter its crimes. Imagine a world where Moscow incorporates this into its wartime strategy, taking hostages at will, whereas the West has to turn over veritable murderers and spies. In such a world, the Kremlin could counter any Ukrainian successes on the battlefield by snatching up a hostage to undermine this progress or even force concessions. It is not only people within Russia who are at risk. The Kremlin is becoming increasingly adept at transnational repression, going as far as snatching an activist from a neighboring country.

In order to make sure the swap is not in vain, Western policymakers and the public must make sure to not let up. The pressure and diplomacy must continue, and Russian political prisoners must become a key element of Western engagement with Russia. Policymakers should also provide safe havens to Russian exiled dissidents and provide them with the platforms and funds they need to do their jobs — not slam doors in front of them by denying visas and shutting them off from decision-making.

Anyone who supports Russian civil society can make a difference, even if they do not hold office. You can follow independent media and NGOs who work tirelessly toward building a better Russia at peace with itself and the world. You can push your political representatives to do better. You can also donate and write letters to political prisoners still languishing in the Kremlin’s jails.

There are so many ways in which you can help — just do not give up! We have to make sure that the exchange is only the first step in a campaign to make a Russia that respects human rights a reality.

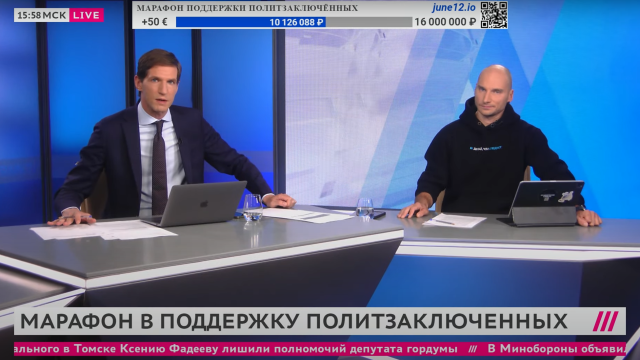

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.