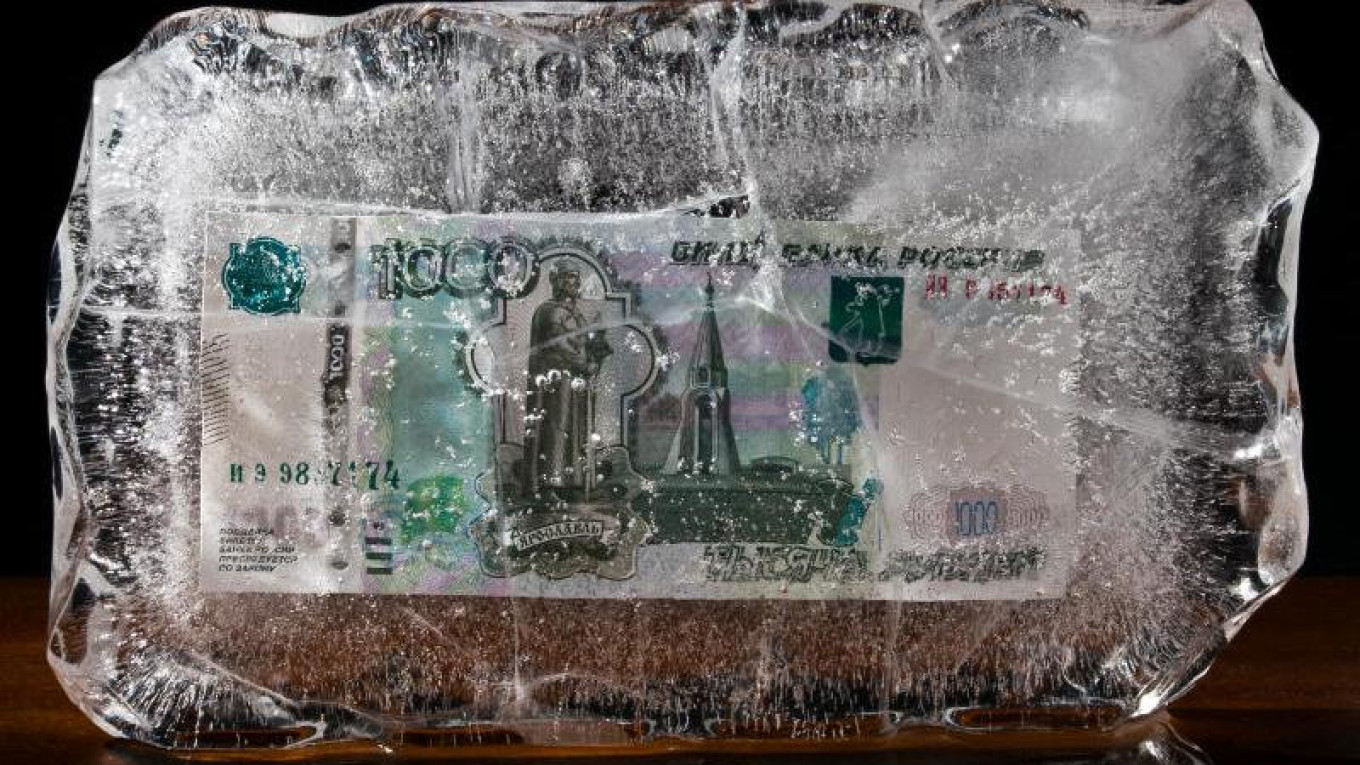

Russia’s recovery from the current recession continues to slow, according to the Economic Development Ministry. The reason: demand has plummeted. If that is the case, it means the Russian economy’s decline is in full swing despite official statements that the recession has ended.

The decline in retail turnover – the primary indicator of consumption – accelerated in December. The entire last quarter as a whole, has been tough for retailers. The largest retailers either saw declines in revenues or the rate of growth slow. One in every three retailers complained of a drop in demand at the end of last year, according to the State Statistics Service. That was worse than the previous quarter, which means that consumers are economizing even more now.

The Russian middle class has nearly exhausted its savings, says Lilia Ovcharova, director of the Higher School of Economics Institute for Social Policy. Previously, 60 percent of the population either chose not to make any purchases or opted for less expensive alternatives. Now that figure stands at 75 percent. The number of those expecting the economic crisis to continue for some time has ballooned.

The Higher School of Economics also points out that most people have responded passively to the crisis, with 40 percent opting for less expensive products and 40 percent buying fewer goods. At the same time, more people are looking for higher-paying jobs (18 percent) or farming additional plots of land (14 percent).

However, without savings to ride out the transition, even looking for a new job can be difficult.

More than half of Russians had no savings before the current crisis, much less now. On average, Russians devoted only 10 percent of their incomes to savings from January to November of 2016, down 25 percent from the same period in 2015.

According to the HSE, among those who have savings, 70 percent can live on them for one month without changing their lifestyles, and 33 percent only one week.

The search for better jobs is causing an increase in off-the-books employment and salaries, with up to 12 percent of legally employed respondents also holding unofficial jobs in November 2016, against 7 percent a year earlier, according to RANEPA

As many as 79 percent of Russians cut back on expenses for goods and services in November 2016, versus 75 percent in November 2015.

Real incomes have been falling for the past three years, but that decline accelerated in 2016 when the government stopped indexing pensions and social benefits to inflation. The buying power of the average per capita income in Russia fell 10 percent from 2013 to 2016.

Retail turnover dropped by 14 percent over that period, with food sales falling even more than non-food goods. That is a sign of high — and growing — inequality, said Ovcharova.

According to the HSE, 40 percent of Russians in 2016 considered themselves poor – meaning that they lacked money for food or had only enough for food. The growth of that subjective indicator was greatest among families with children, with 47 percent considereding themselves poor in November 2016, as compared to 38 percent who felt that way in March.

Russia is seeing not just a decline in consumption, but a fundamental change in the consumer basket – primarily among Russians with low incomes who simply cannot afford to purchase anything other than vital necessities, according HSE Center for Market Research director Georgy Ostapkovich.

Russia’s economic recovery has stopped, but people have grown used to the crisis: 40 percent consider themselves poor, but only 22 percent consider their economic situation bad or very bad. That means they are grown accustomed to it.

The Higher School of Economics also points out that most people have responded passively to the crisis, with 40 percent opting for less expensive products and 40 percent buying fewer goods. At the same time, more people are looking for higher-paying jobs (18 percent) or farming additional plots of land (14 percent).

However, without savings to ride out the transition, even looking for a new job can be difficult.

More than half of Russians had no savings before the current crisis, much less now. On average, Russians devoted only 10 percent of their incomes to savings from January to November of 2016, down 25 percent from the same period in 2015.

According to the HSE, among those who have savings, 70 percent can live on them for one month without changing their lifestyles, and 33 percent only one week.

The search for better jobs is causing an increase in off-the-books employment and salaries, with up to 12 percent of legally employed respondents also holding unofficial jobs in November 2016, against 7 percent a year earlier, according to RANEPA

As many as 79 percent of Russians cut back on expenses for goods and services in November 2016, versus 75 percent in November 2015.

Real incomes have been falling for the past three years, but that decline accelerated in 2016 when the government stopped indexing pensions and social benefits to inflation. The buying power of the average per capita income in Russia fell 10 percent from 2013 to 2016.

Retail turnover dropped by 14 percent over that period, with food sales falling even more than non-food goods. That is a sign of high — and growing — inequality, said Ovcharova.

According to the HSE, 40 percent of Russians in 2016 considered themselves poor – meaning that they lacked money for food or had only enough for food. The growth of that subjective indicator was greatest among families with children, with 47 percent considereding themselves poor in November 2016, as compared to 38 percent who felt that way in March.

Russia is seeing not just a decline in consumption, but a fundamental change in the consumer basket – primarily among Russians with low incomes who simply cannot afford to purchase anything other than vital necessities, according HSE Center for Market Research director Georgy Ostapkovich.

Russia’s economic recovery has stopped, but people have grown used to the crisis: 40 percent consider themselves poor, but only 22 percent consider their economic situation bad or very bad. That means they are grown accustomed to it.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.