Despite news reports of a “pro-Russian” party’s victory in last Saturday’s parliamentary election in Latvia, the election provides evidence that if Russian President Vladimir Putin makes any inroads in the Baltic states, it won’t be through their democratic institutions.

There’s little doubt that Putin has his eye on the Baltics. As the Kremlin faces European sanctions for its Ukrainian adventures, it’s only natural to look for a backdoor into the European Union through the large Russian minorities of Estonia and Latvia — about a quarter of each country’s population — which often watch Russian state TV and end up in Russian-language filter bubbles on the social networks.

“Putin will try to make sure your politicians don’t feel safe,” Mikhail Khodorkovsky, formerly Russia’s richest man, now a political exile and one of Putin’s highest-profile Russian opponents, told a Latvian magazine last month. “Leaning on marginal forces that exist in any country, he’ll amplify conflicts. The goal is to weaken the political elite, make it feel dependent.”

Yet Latvia’s election results, as well as demographic trends there and in Estonia next door, show how hard it would be to reach that goal.

What ‘Pro-Russian’ Actually Means

Harmony, the center-left Latvian party that came in first on Saturday with 19.8 percent of the vote, is easy to call “pro-Russian.” Its leader, Nils Usakovs, mayor of the capital, Riga, is an ethnic Russian, and so is Vjaceslavs Dombrovskis, the party’s candidate for prime minister. Harmony used to have a cooperation agreement with Putin’s United Russia. And Latvian Russians have long preferred it to other parties because it has pledged to make it easier to get an education in Russian and to maintain closer economic ties with its giant neighbor.

So, has a pro-Russian party won the election? Not really.

Usakovs has long wanted to trade his party’s “Russian” image for that of a mainstream social-democratic political force. Harmony dissolved the United Russia agreement last year when it joined the Party of European Socialists, which unites all the most influential center-left forces in the European Union. For Saturday’s elections, it recruited ethnic Latvian politicians, some with government experience, to head its regional campaigns; Dombrovskis was the only Russian in the campaign’s top ranks. “All these years,” Usakovs said in a recent TV interview, “we have worked on turning into a fully-fledged party that can unite Latvians and non-Latvians.”

This attempt to straddle an electorate divided along ethnic lines makes it all but impossible for Harmony to pursue strongly pro-Kremlin policies.

“We support the European Union’s united stance on Russia no matter what it is,” said Usakovs, adding that Latvia is one of the countries paying most dearly for Europe’s sanctions against Russia. This is a weaker stance on sanctions than that of Italy’s League party or Austria’s far-right Freedom Party; both have active cooperation agreements with United Russia and both are part of their countries’ governments.

Usakovs’s attempts to shed the “pro-Russian” image probably undermined Harmony’s electoral performance. It won 28.4 percent of the vote in 2011, 23 percent in 2014 and less than 20 percent in 2018. Harmony has lost 36 percent of its ballot support since 2011, both because of its own reduced popularity and because of shrinking election turnouts in a country suffering from depopulation.

Simply put, Harmony managed to pick up few Latvian votes but lost quite a few Russian ones. Some of these went to the Latvian Russian Union, a fringe party more favored by the Kremlin than Harmony because it advances one of Putin’s favorite ideas — that of a “Russian world” to which ethnic Russians belong wherever they live. But the Latvian Russian Union only won 3.2 percent of the vote, failing to get into parliament.

After the previous two elections, in which Harmony also finished first, other parties kept it out of government because they saw it as a Russian Trojan horse. A coalition without Harmony will be attempted this year, too, though it’ll be harder to make deals given the success of KPV LV, the populist party led by the actor and radio host Artuss Kaimins. The anti-elite, anti-corruption KPV LV (“That’s it, guys, the party is over,” its leaders have threatened to tell the old political elite after the election) won 14.2 percent of the vote, coming in second after Harmony.

But even if Usakovs’s party ends up in government, it’s unlikely that Latvia will turn more pro-Russian. The realities of coalition government will keep any pro-Moscow sentiments in check. That’s what happened in Estonia, where the Center Party, which has its own lapsed cooperation agreement with United Russia and which most local Russians traditionally back, has been the senior partner in the governing coalition since 2016.

When Mihhail Korb, a Center Party member and minister of public administration, mentioned last year that he wasn’t in favor of Estonia’s membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, it only took a day for Prime Minister Juri Ratas, also from the Center Party, to kick him out of the cabinet. Korb issued an apology, saying that NATO membership was essential for Estonia. Ratas has also been careful not to appear too pro-Russian on domestic issues such as cultural autonomy for the Russian-speaking minority.

“The party leadership only needs Russians to pick up votes,” said Rodion Denissov, publisher of the Russian-language Estonian news outlet Tribuna.ee. “The problem is that there are no alternatives: Other parties just berate Russia and Russians, so people keep voting Center even though they trust it less and less.”

Loyal to Their Pocketbooks

The ethnic Russians of Latvia and Estonia aren’t, for the most part, members or any potential fifth column. They are increasingly integrated, perhaps not so much into the Baltic states themselves as into the borderless Europe.

“Excluded from the public sector in the 1990s and early 2000s as a result of citizenship and/or language policy, ethnic Russians established businesses in Estonia and Latvia’s flourishing private sectors,” Michele Commercio of the University of Vermont wrote earlier this year. “Economic stability, and in some cases prosperity, along with EU and NATO membership, discouraged Russians from leaving Estonia and Latvia and from protesting nationalisation policies in these countries. Indeed, it encouraged them to take advantage of available economic opportunities, naturalise, and raise their children bilingually. The end result is a new generation of integrated, bilingual ethnic Russians who are content with their lives in Estonia and Latvia.”

That is a bit of an oversimplification. In Estonia, according to official statistics, some 27 percent of ethnic Russians are officially at risk of poverty, compared with 18.7 percent of ethnic Estonians. It’s not as if all ethnic Russians channeled their frustrated civic zeal into business activity; many have simply fallen by the wayside. But, for the most part, Russians in both Estonia and Latvia have figured out how to work the existing system, initially hostile to them, to their advantage.

Latvia and Estonia granted citizenship to the few Russians who found themselves on their territory after the fall of the Soviet Union, hoping they would go home. Tough language tests were required to get on the citizenship path. As a result, today, only 64 percent of Latvia’s ethnic Russians are citizens of Latvia, according to official data; in Estonia, the figure is 41 percent. The rest are split between Russian citizens (a minority) and holders of so-called alien passports that, for some people, provide the best of both worlds — visa-free travel both throughout the EU and to Russia (Latvian and Estonian citizens require visas for Russia). Just as Commercio pointed out, many of the alien-passport holders have willingly sacrificed their ability to vote in national elections for the chance to do business between Russia and the EU.

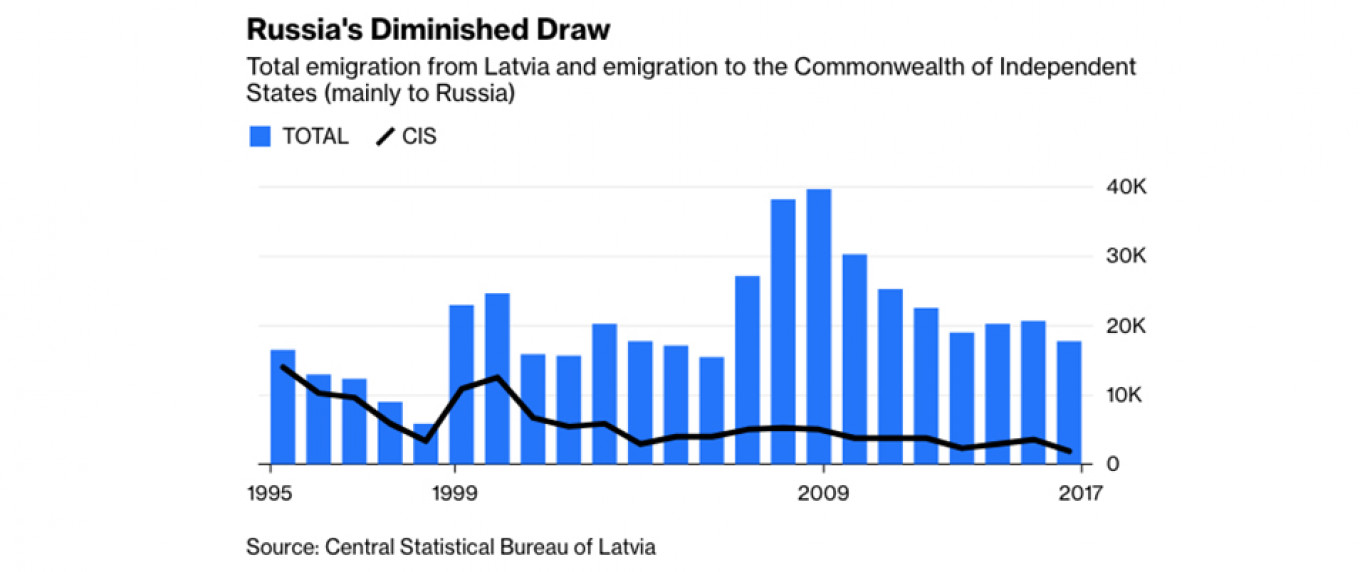

Latvia has been steadily losing its population ever since it gained independence in 1991. Initially, other former Soviet republics, especially Russia, were the biggest destination for Latvia’s emigres. The wealthier EU nations took over at the turn of the century.

Russia's Diminished Draw

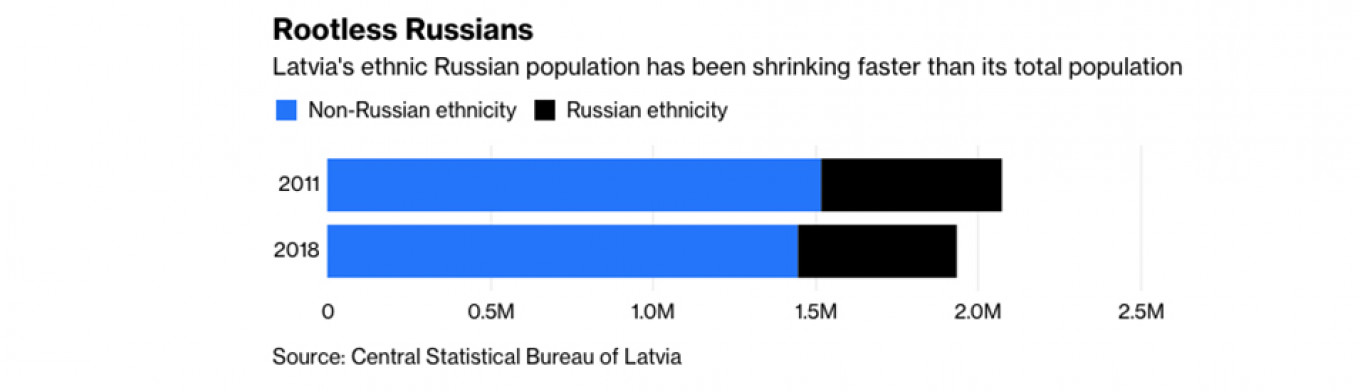

Latvia is still losing people to them — and it’s losing ethnic Russians faster than residents in general. The new, European Russians, bred without any particular loyalty to their Baltic country of birth but without meaningful ties to Russia either, move away readily to seek their fortunes.

Rootless Russians

Estonia is a wealthier country than Latvia — the average pension has reached 400 euros ($458) a month there, while in Latvia, it’s 320 euros and raising it to 400 was a key Harmony election promise. Not coincidentally, Estonia has boasted positive net migration for the last three years. Its government statistical agency reports an influx of people with Russian citizenship; the small nation has become a magnet for Putin opponents who don’t want to move too far away, and several well-known activists have settled there in recent years.

If the Baltic nations have to worry about any Russians at all, it’s those who were born in these countries but have Russian citizenship. These are largely people who have chosen the “Russian world.” But there are only 17,761 such people in Estonia and 8,626 of them in Latvia. These aren’t large numbers — 1.3 percent and 0.4 percent of the population, respectively — no fearsome fifth columns are anywhere on the horizon.

Latvia has more to fear from its continuing depopulation. It’s the young, well-trained people of every possible ethnicity who seek their fortunes overseas; that may explain the growing support of populist parties, backed by a less mobile rural population. Building up a social safety net, as Estonia is doing, could be a partial answer to the problem.

As for the ethnic Russians, their behavior, including the determined centrist voting, mobility and economic activity, presents no danger to the Baltic states. Rather, it shows how Russians might have come to behave if Russia itself had never veered off the path of Westernization, which could have led it to the European Union. They’d still be Russians, but also Europeans. There’s nothing Putin’s anti-Western project has to offer them.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics and business. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru. The views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.