(Bloomberg View) — After a disappointing French presidential election, Russian President Vladimir Putin appears to get closer to what he wants in Italy. After the March election, it is almost certain to get both a pro-Russian government and a sizable pro-Russian opposition. They will likely make sure that the European Union won't expand sanctions against Russia -- but the sanctions are unlikely to be lifted.

The Kremlin's policy, based largely on economic interest, is to drive a wedge between the U.S. and the EU on sanctions policy, making sure Russia retains its ability to extract and export energy resources and attract market funding both for the state and for Russian companies. EU sanctions, imposed on Russia for annexing Crimea and stoking the fighting in eastern Ukraine, were initially in line with U.S. ones.

But while the U.S. kept adding punitive measures, the EU has largely rolled over the old ones. In November 2014, 132 individuals and 28 entities were subject to sanctions in Europe. That's only grown to 150 people and 38 entities by now. A search in the U.S. sanctioned persons database yields a total of 569 people and firms penalized under four Ukraine-related executive orders.

The European Council, which consists of EU national leaders, must make sanctions decisions unanimously. In Russia's case, it has done so more than two dozen times. The big prize for Russia, then, is to get a dissenter who would vote against an extension of the restrictions.

It can't be Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orban openly admires Putin; Cyprus, inundated with Russian money; or Austria, where the nationalist Freedom Party, the junior partner in the current ruling coalition, has a cooperation agreement with Putin's United Russia party.

For these small nations, the cost of open rebellion against EU unity on a highly visible matter outweighs any economic benefits from increased trade with Russia. U.S. anger unmitigated by any EU protection can also be scary to them.

The dissenter Russia needs must be a big country, preferably one of the four classified as desirable "strategic partners" from the Kremlin's perspective in a 2007 European Council on Foreign Relations paper — countries that "enjoy a 'special relationship' with Russia which occasionally undermines common EU policies." These are France, Germany, Italy and Spain, all countries big enough to assert foreign policy independence both from the EU and from the U.S.

Germany, whose leader Angela Merkel pushed other EU nations to fall into line on sanctions, and Spain, where the government is not Kremlin-friendly, are out for now.

In the French presidential election last year, Russia had two promising avenues of attack -- through nationalist candidate Marine Le Pen and her conservative rival Francois Fillon. Both were passionate opponents of the sanctions, but Fillon, a mainstream candidate, was the more realistic bet for the Kremlin. He was the election front-runner until a corruption scandal destroyed his bid.

Then Le Pen, too, lost to Emmanuel Macron, who wants to bond with Merkel.

That leaves Italy. It has had the most special of special relationships with Russia since Soviet times, when the strong left-wing element in Italian politics kept the country on the fringe of the Cold War. In the 1960s, Italy supplied more than half of the industrial equipment that the Soviet Union imported, ENI was a key strategic partner for the Soviet oil industry, and Fiat built what is still Russia's biggest car factory — in a city newly renamed Togliatti to honor Palmiro Togliatti, the long-time leader of the Italian Communist Party, who died in 1964. Soviets saw more Italian movies than Hollywood ones.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, the special relationship flourished. Even technocratic, eurocentric Italian leaders have been relatively pro-Russian. Romano Prodi, the Italian prime minister who went on to head the European Commission, once said that "Russia and Italy are together like vodka and caviar, an excellent combination."

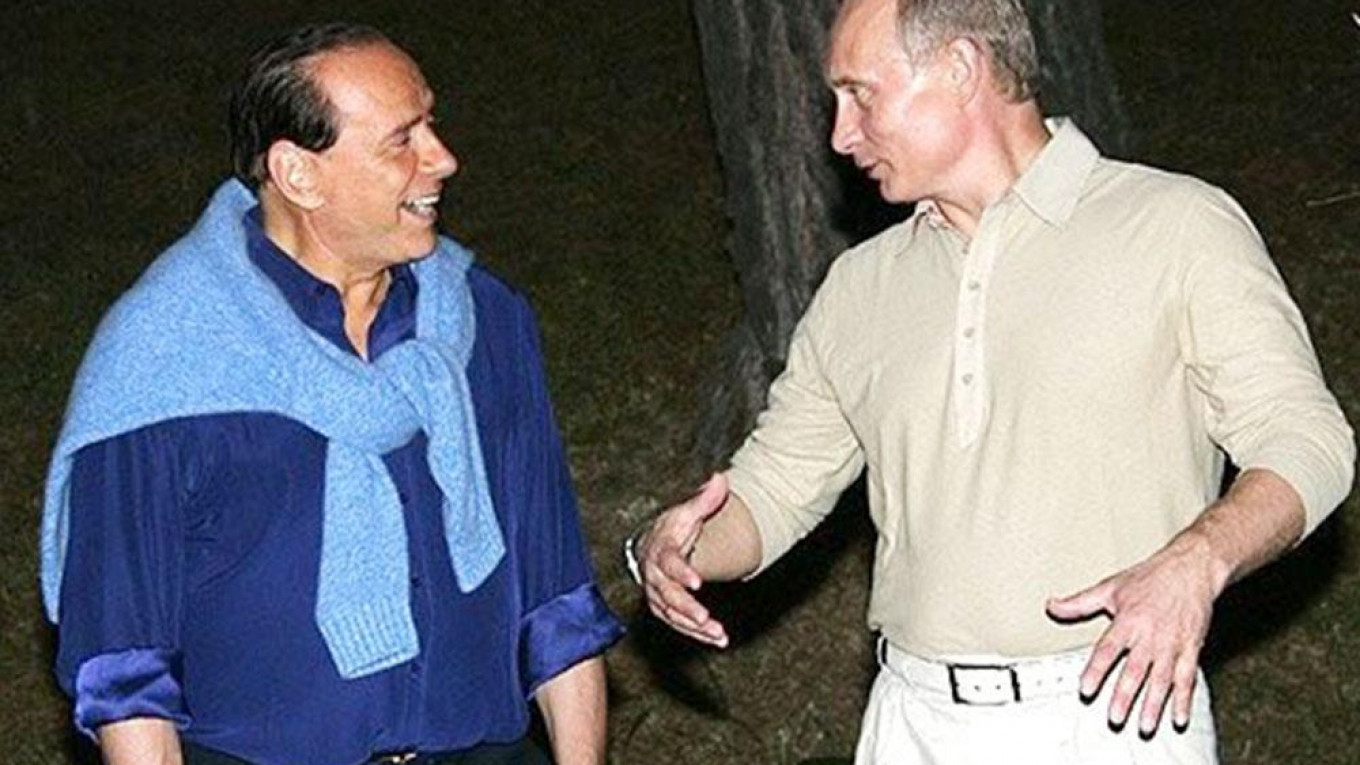

That, however, is not a flowery enough compliment to describe Putin's close friendship with another Italian leader, Silvio Berlusconi.

When the media tycoon was swept out of power by one scandal too many, Putin, according to one report, even offered him Russian citizenship and the economy minister's job.

In 2015, with the sanctions already in force, Berlusconi visited Crimea with Putin — and tasted 240-year-old sherry from the cellars of Massandra, which should legally still be considered a Ukrainian state enterprise but which was taken over by Russia after the annexation. And last year, Berlusconi's birthday gift to Putin was a duvet cover printed with a large picture of them shaking hands.

Berlusconi, of course, is the force behind the right-wing comeback ahead of the March election. He won't be prime minister because of a criminal conviction, but his Forza Italia has the potential to build a governing coalition with the right-wing Northern League party — another strongly pro-Russian force and the signatory of a cooperation agreement with United Russia. Overturning Russia sanctions is part of the party's program.

The populist Five Star Movement is opposed to the sanctions, too. It has vocally supported the Russian military operation in Syria.

Even the center-left Democratic Party, which has led the latest Italian governments, isn't particularly anti-Putin. Despite U.S. pressure, Italy has blocked attempts to expand Russia sanctions in response to Putin's Syria intervention.

The motives behind Russia's popularity in Italy aren't just cultural and historical but also economic. Italian businesses are still strongly represented in Russia; the bank Intesa Sanpaolo was a key player in the recent controversial sale of a 19.5 percent stake in Russia's state-owned oil producer Rosneft, whose chief executive officer, Igor Sechin, is a close friend of Putin and sanctioned by the U.S. The EU sanctions have hurt Italy.

The biggest exporter to Russia in the EU after Germany, it's unhappy about a 40 percent drop in these exports since the sanctions were introduced. A pro-sanctions position would be hard to sell to business lobbies.

Putin must be pleased with this landscape. This, however, is Italy, with a tradition of messy governance and unstable alliances. No party or group of ideologically close parties stands to win outright in March. In some sort of broad coalition (which Five Star would be allergic to joining), any and all positions will be diluted, and the leader of an unstable government will be unlikely to start an EU-level rebellion just to help Putin.

It's clear that Italy won't be interested in heeding U.S. calls for further anti-Kremlin action — but then neither are a number of other countries. In that sense, nothing much will change for the Kremlin — and the last of the four countries that could have ended the sanctions will be eliminated.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru. The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.