The propaganda campaign by President Vladimir Putin's regime has convinced Russians that the West, and especially the United States, devotes a lot of thought to Russia. Why? Because the West is full of "Russophobes."

I first encountered the terms "Russophobia" and "Russophobe" during the Soviet era while reading literary journals that published the work of so-called "patriot writers." They were a separate class of authors who built their careers on highlighting the shortcomings of Western culture as compared to traditional "Russian values."

However, the word Russophobe never found usage at the official state level. It is quite another story today. Both the foreign minister and culture minster frequently use the word in their official statements.

Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky banned certain stage productions and movies on the grounds that they were Russophobic. The most famous, but far from the only such case was his decision this spring to ban the showing of the Hollywood film "Child 44" on the claim that it was Russophobic.

The Russian company that had purchased Russian distribution rights to the film quickly fell in line with the decision, even though that obedience resulted in losses totaling 50 million rubles (approximately $1 million). Rumor has it that Putin was outraged after viewing the movie prior to its official Russian debut. Hence, the ban.

Of course, the Kremlin could probably find "Russophobic tendencies" in every Hollywood production about Russia — that is, if it chose to equate blockbuster entertainment with Discovery Channel-style documentaries. But that would be like complaining that Mickey Mouse's ears look nothing like the real thing.

In all of these so-called Russophobic films, viewers should understand the depiction of Russia as something of a convention — and one that reveals as much about the filmmakers as it does about Russia.

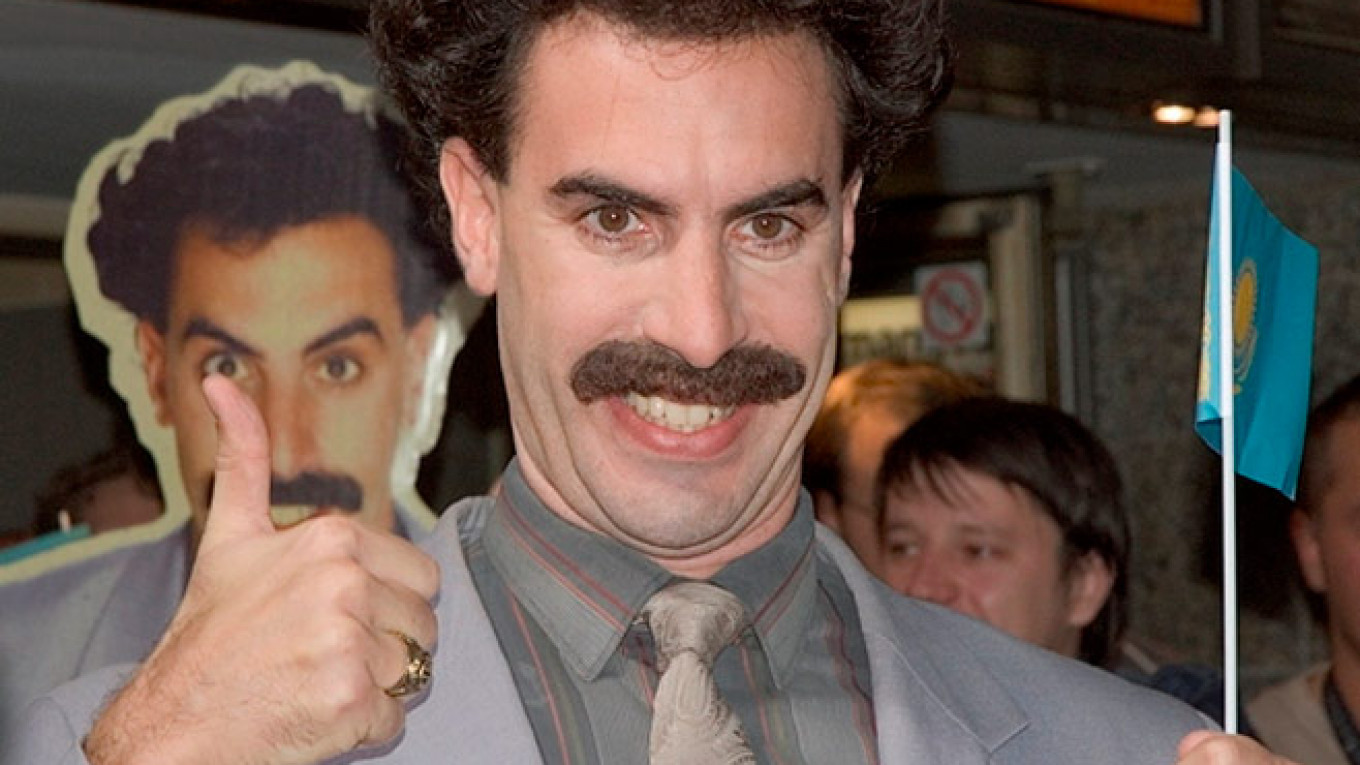

Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev had enough sense not to ban the film "Borat," even though his advisers warned him that it made Kazakhstan look bad and was riddled with lies. Nazarbayev realized that "Borat" was based on a fictional notion of the country, not Kazakhstan as it really exists.

In 1997, Volvo invited journalists — myself and other Russian correspondents included — to a Hollywood preview of the movie "The Saint" starring Val Kilmer and featuring Volvo automobiles as a form of product placement.

Today, Russian authorities would definitely accuse "The Saint" of distorting reality, even though it was filmed not in a studio, but on the streets of Moscow. For example, Val Kilmer climbs up the steeple of the real Hotel Ukraina, fires his gun, and then runs from his pursuers along the rooftop.

The plot of the film has Kilmer trying to save the world from a Russian threat: It turns out that the Russians have created an ultra-powerful generator that would allow the fictional Russian President Karpov to subjugate the entire world.

Of course, the president has ties to gangsters, and so crime bosses team up with the FSB to pursue Kilmer. And what curious scenes of everyday Russian family life the films depicts, along with a Moscow restaurant with bears, balalaikas, prostitutes and a mafia hideout tucked behind the kitchen area.

Every apartment building even has a barrel of oil in the basement to keep the residents warm on those cold Russian nights. It is fun to watch, perhaps, but obviously just a fantasy.

However, a Russian consultant advised the filmmakers. As I sat in the Hollywood screening room and watched the closing credits roll by, there in big letters I read: "Many thanks to Nikita Mikhalkov."

And now Mikhalkov, Russia's iconic filmmaker, never loses an opportunity to warn Russian television viewers about those Russophobes who "distort the truth about Russia."

Andrei Malgin is a journalist, literary critic and blogger.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.