When David first came to Moscow 10 years ago, he stood out like a sore thumb. People stared at him. On public transportation, other passengers avoided sitting next to him. Even his marriage provoked speculation. Many accused him of marrying his wife Natasha for financial reasons.

People treated him as though he were “from another planet,” he says. “I tried to ignore it. It was too painful.”

Both David and Natasha are African, in a sense. The challenge is that David is black and Natasha is white. Born to Soviet diplomats in the Republic of Congo, Natasha spent her formative years in Africa, speaking French better than Russian. She says that being married to David, a Nigerian former professional soccer player, is normal for her and her parents.

Not all of Moscow agrees.

“Mixed” or “international” marriages are not uncommon in today’s Russia, but they are still far from the norm. The collapse of the Soviet Union, which opened the country to foreigners, also opened the floodgates to increased national sentiment.

In multicultural Moscow—an international city, but less so than many in the West—love across racial, ethnic, and national boundaries still poses particular challenges.

Festival Children

Natasha and David—who asked to be identified by pseudonym —represent an extreme example of the challenges of “mixed marriages.” A Russian-African union is likely the most “exotic” pairing imaginable for most Russians.

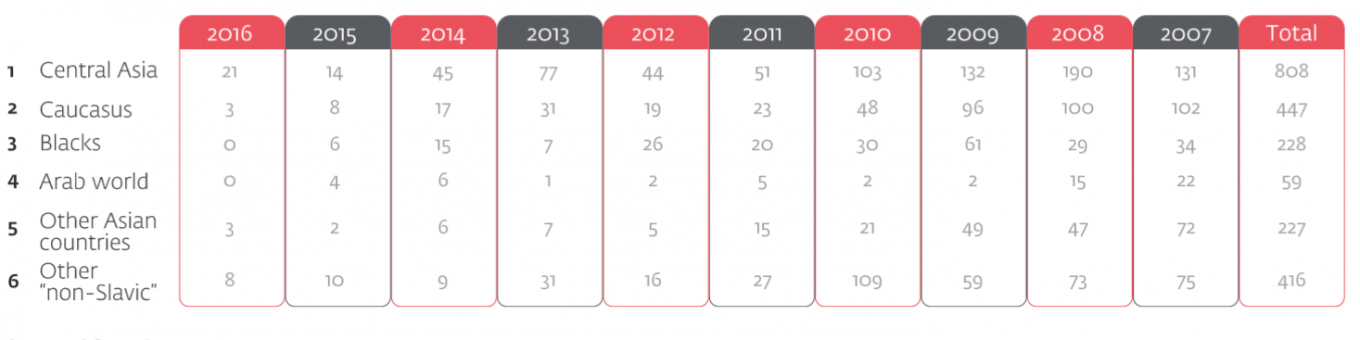

Their desire for anonymity is understandable. Black Africans are frequent targets of violence from skinheads in Russia. According to data from SOVA Center, an anti-extremism monitoring organization, blacks are the third most targeted group in Russia after Central Asians and people from the Caucasus — a remarkable statistic, given the African diaspora’s small numbers in Russia.

But the challenges of Natasha and David’s marriage are hardly unique. An October 2016 poll by the independent Levada Center pollster found that 52 percent of Russians support the nationalist slogan “Russia for Russians,” while only 12 percent felt that immigrants enrich Russian society.

Nor is the problem simply the novelty of mixed marriages. The Soviet Union, a country with hundreds of ethnicities, also had mixed couples. According to a common stereotype from the Soviet period, romances would sometimes bloom between young African and South America men — often students or members of youth delegations — and local Russian women. The children of these unions were called “festival children” after the 1957 World Festival of Youth and Students, held in Moscow.

The problem is changing norms, says

Elena Khanga, a Russian journalist born to a Zanzibari father and and

a mother of African-American and Jewish ancestry. When she was

growing up in the Soviet Union, “friendship of nations” was state

policy and any manifestation of racism by a public figure was seen as

indecent.

“Unfortunately, nowadays there is no such policy,” Khanga says.

Overcoming Stereotypes

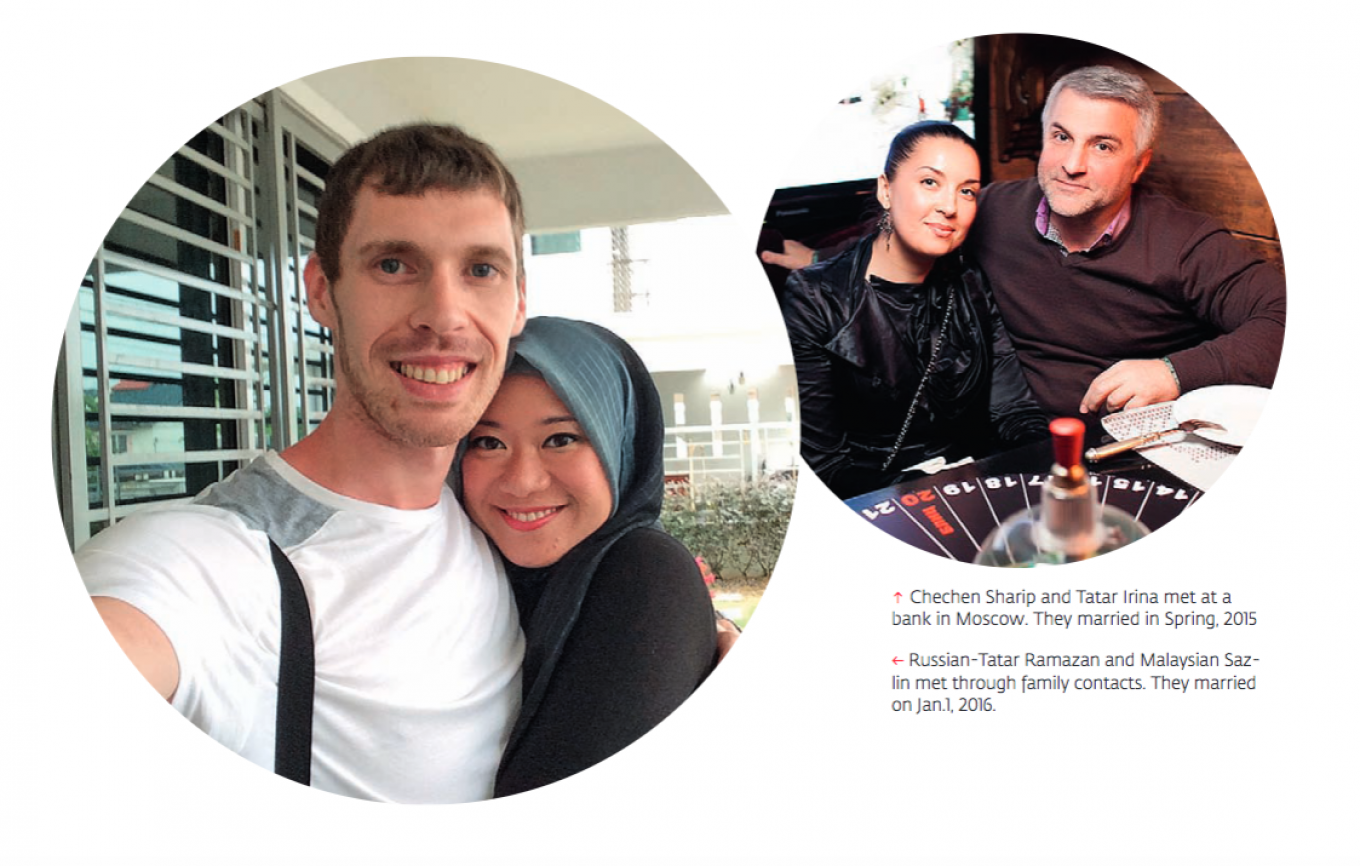

Sharip Dzhabirov was a successful real estate entrepreneur, but his romantic prospects looked dim. He was 50 years old, divorced, with three children and a nephew living with him. He was also Chechen—“all solid disadvantages,” he says.

Negative stereotypes, combined with two bloody separatist wars in Chechnya, led many Russians to view Chechens as uncultured and aggressive. Alongside his complicated family situation, this seemed like a lot of baggage to Sharip.

Then, at a breakfast hosted by a bank where he was setting up an account, he met Irina Ayatova. She had a child of her own and could understand his predicament. As an ethnic Tatar, Sharip was encouraged that she “knew Islam.” She also related well to his children.

“I never imagined that I would find a woman who could accept and respect my children,” Sharip says.

Both families were supportive of Sharip and Irina’s decision to marry and start a family together. But there were some reservations. Sharip says his Chechen relatives would have “preferred I marry a Chechen.”

Irina’s parents and friends also had concerns—unfortunately, Chechens “provoke a subjective reaction,” she says euphemistically. However, once they met Sharip, both her parents and friends were relieved.

In fact, both Sharip and Irina say that the biggest challenges were not cultural, but practical: how to unite two separate families with their own lifestyles, habits, and routines.

Have Faith

Religion can be one of the biggest challenges in mixed marriages. It can also be the factor that helps to unite people from different backgrounds. Vladimir Ten saw this first hand.

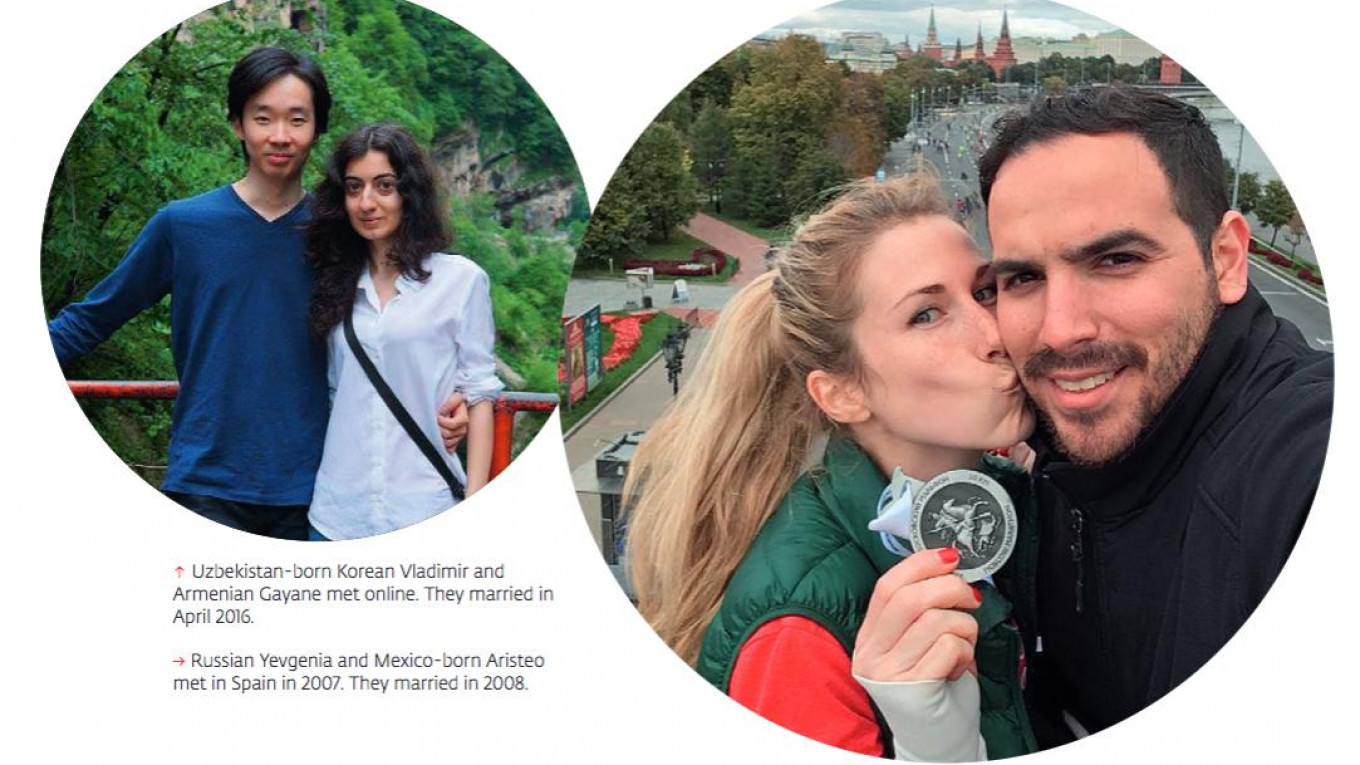

In 2014, Vladimir was surfing Russian social network site VKontakte when he came across a girl named Anna Kim. An ethnic Korean born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan Vladimir had been looking to meet a girl in the Korean community. He decided to write Anna a message.

But things were not as they seemed. Anna Kim was actually the alias of Gayane Khachtryan. Born in Yerevan, Armenia, Gayane had grown up in Moscow. At the time, she was working for a think tank and carrying out research on different ethnic diasporas in Russia. She had become Anna Kim to get a window into Korean community.

Despite the initial deception, Vladimir and Gayane continued talking and eventually started dating. However, they were a bit concerned about what their families would think. On the whole, Moscow has little problem with interracial relationships, Vladimir says. However, most Koreans and Armenians tend to favor marrying within their own group. Religion was also a challenge.

My family is religious, and they were a bit concerned that Vladimir’s family is not baptised,” Gayane, 28, says. However, after talking with Gayane’s parents, they were able to get their approval. Both are thankful it was not more difficult.

“We’re lucky that our families are not extremely conservative,” Vladimir, 26, says.

Long Distance Love

Practical challenges like these are something Yevgenia Novokhatnaya understands well. She and her husband Aristeo Gonzalez, a Mexican national, live over 10,000 kilometers apart while he is studying to become a diplomat in Mexico City.

Yevgenia and Aristeo met in Spain during a New Year’s trip in 2007. After more than a year of emailing, writing, and visiting one another in Mexico, Paris and Madrid, they got married in 2008. She was 24. He was 21.

Because Aristeo still had two years left at university, the young couple made a drastic decision: to move to Mexico. Yevgenia’s parents were suspicious. Her mother even challenged the plan: “The Mexicans all run to the United States. Will you be running too?” she said.

Yevgenia admits her first months in Mexico were difficult. She knew no Spanish and struggled to integrate with the culture. Aristeo encountered the same issues in Russia. Ultimately, his need to build his career brought him back to Mexico. For the last year, they have spent only four months together—a challenge unique to an international relationship.

If there was one cultural challenge that stood out for Yevgenia, it was adjusting to her Mexican in-law’s staunch Catholicism. Her Mexican family always prayed before meals and attended church every Sunday, something foreign to Yevgenia. Mexican people are “much more devout than most of the Orthodox Christians I know,” she says.

Love is… Bureaucracy

Religion was what helped unite Russian Tatar Ramazan Akhmetshin and Malaysian Sazlin Zainudin. In 2014, Ramazan, an IT specialist in Kazan, the capital of Russia’s Republic of Tatarstan, began thinking about marriage.

He was almost thirty. It was time, he thought. Nearly, 7,500 kilometers away in Kuala Lampur, Malaysia, Sazlin Zainudin, who had just finished an MBA, was having similar thoughts. One of Sazlin’s friends was married to a Tatar, whose mother was friends with Ramazan’s parents.

That was their connection. Soon they had exchanged pictures and were chatting over Skype and Whatsapp. Several months later, Ramazan travelled to Kuala Lampur. On Jan. 1, 2016, they got married.

Neither had planned to marry a citizen of another country —“but maybe someone else had such a plan,” Ramazan says, glancing upward. Support from both families eased their decision to marry. What’s more, interracial marriage is fairly common in Malaysia. They were also both religious Muslims.

“There were no contradictions in terms of religion, so it was easier for us,” Sazlin says.

Today, Ramazan, 30, and Sazlin, 34, live in Kazan. In a city known for Muslim-Christian harmony, they say their international and interracial marriage has been welcomed. The biggest challenges have been bureaucratic.

Unlike many other countries, Russia has no simple spousal visa. As a result, Sazlin had to travel back and forth between Russia and Malaysia. They have since resolved the visa problem—for now. Sazlin is currently studying Russian at the local university, which gives her visa support.

A Changing City

For all the challenges faced by international and interracial couples in Russia, no one interviewed by The Moscow Times suggested that they were insurmountable. Despite some initial difficulties, Sharip and Irina managed to unite their two households by creating family traditions that could bring everyone together. And Yevgenia and Aristeo — who have had to traverse continents together and spend months apart — have been married for nearly 10 years.

Even Natasha and David, who initially encountered racism in Russia, say the situation in Moscow is improving. Like many mixed couples, they say that most Muscovites are now largely indifferent to such marriages.

It’s a development that runs somewhat contrary to official narratives. Russian politicians and state-controlled media increasingly promote an idea of “us” and “them,” and a sense of Russian exceptionalism. Meanwhile, prejudice toward people from Central Asia and the Caucasian republics certainly persists, and the construction of mosques remains a divisive issue in Moscow. In theory, all this should point to an increasingly polarized society.

But, today, Nigerian David says that people no longer stare at him on the metro. Russians, he believes, have grown more used to seeing foreigners in their country, and international marriages have grown increasingly more common across the country.

Life, he says, “is going a lot smoother than I ever expected.”

Meanwhile, Natasha says her family’s internationalism has benefitted her children. The couple’s daughter goes to an English-specialized school, and enjoys a major advantage over her classmates because her father is fluent in English. In that context, she looks cool.

“I gave my kids a chance to be popular,” Natasha says with a laugh.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.