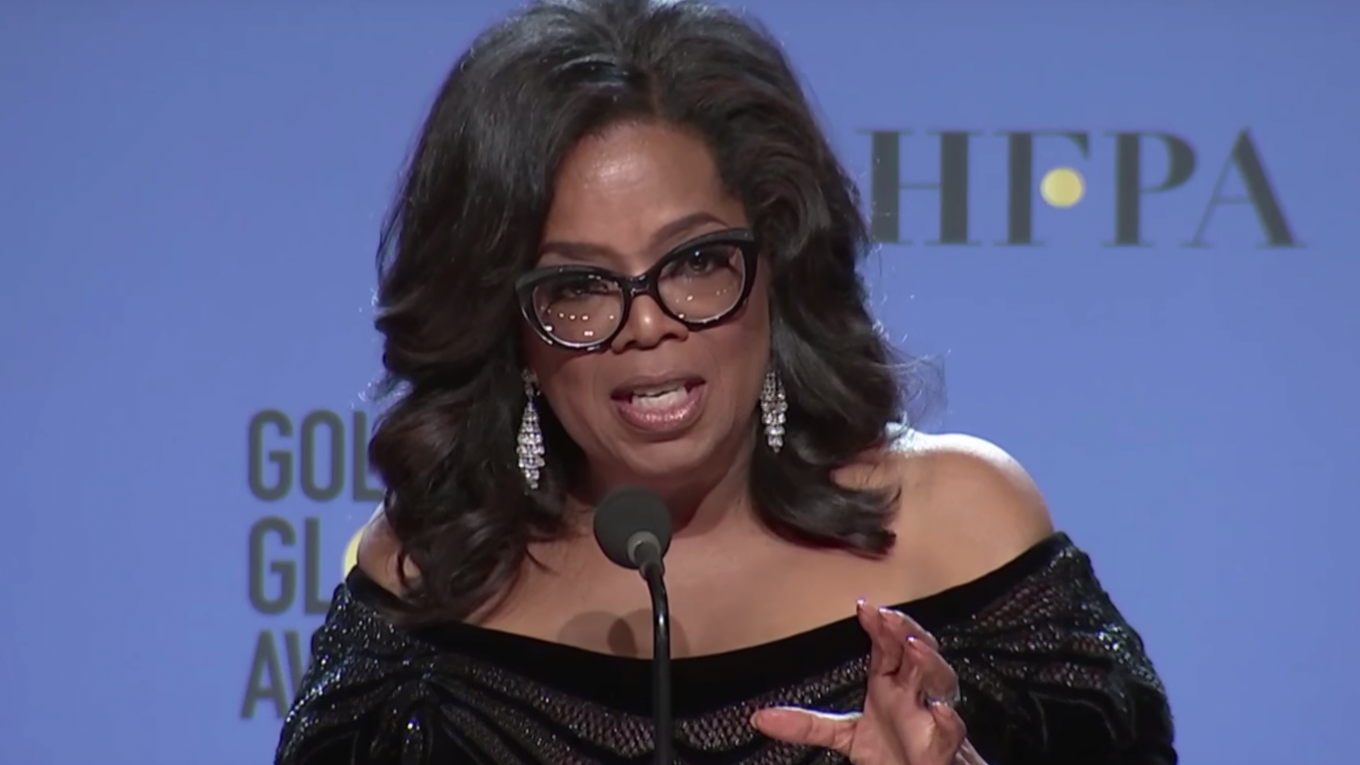

“A new day is on the horizon,” Oprah Winfrey said as she accepted a lifetime achievement award at the Golden Globes. It will be a time “when nobody has to say ‘Me too’ again.”

The #Metoo movement in the U.S., which champions women’s right to dignity and denies men the right to use them as casual objects of sexual desire, appeared in October 2017 and since then has swept the English-speaking world with astonishing speed.

Triggered by two publications in The New York Times and The New Yorker, dozens of prominent men have been toppled from their posts, from Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein and actor Kevin Spacey to former Democratic Senator Al Franken.

Of course, the real catalyst was the election of a U.S. president who brags he can get into the pants of any woman he desires and who considers it good sport to bed a friend's wife.

The Russian reaction to all of this has ranged from the condescending: “Poor chicks, we can’t even pinch their asses now,” to the curious: “I wonder whose head will roll next?”

It comes with a side dish of deliberation on the presumption of innocence (“People are being fired without any evidence”), with commentators forgetting — or not realizing? — that the presumption of innocence applies to criminal acts, and not necessarily to the gray area of inappropriate sexual overtures or manipulation.

Meanwhile, it was enough to watch any of the recent broadcasts for Orthodox Christmas to grasp the scale of the problem in Russia: This is a world of male authority that does not tolerate one iota of the malevolent influence of the West, with its female priests, pastors, rabbis, and congregational leaders.

In Russia, as in the Muslim world, control over people’s minds is all-important. Recall the kilometer-long line of the faithful waiting to catch a glimpse of the sacred remains on display at the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow, or in an earlier day, to view the body of Lenin lying in state in the mausoleum on Red Square.

In these scripts, women have a single role: That of a subservient and silent subordinate who knows her place.

The fact that Olga Golodets serves as Deputy Prime Minister, Veronika Skvortsova as Health Minister, and Elvira Nabiullina as head of the Central Bank should not fool anyone.

Head of the Central Elections Commission Ella Pamfilova’s emotional display in rejecting opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s petition to run for president only underscored how utterly dependent she is on instructions handed down by her male handlers — a world that the writer Vladimir Sorokin described brilliantly and presciently in his book “Day of the Oprichnik.”

Even Navalny showed that he is tainted by sexism, his body language indicating what an outrage it was to be barred from politics, and by a woman, no less. Unthinkable!

The underlying reasons are clearly explained in “Beyond God the Father,” by the renowned theologian and feminist Mary Daly, without euphemism or equivocation. Male-dominated political and public life is based on the belief that the Almighty undoubtedly has a male face, although exactly what that face looks like, no one can say.

I do not want to get entangled in a theological debate here and will avoid arguments such as “all of the apostles of Jesus were men” and “Peter, in Romans 16:1 refers to a female deacon.” But I cannot help but mention that, to my knowledge, not a single text of the Aramaic religions indicates that the male holds primacy over the female (Adam, the first human, after all, was a hermaphrodite.)

Rather, such convictions grew out of political and social traditions that men institutionalised based not on sacred texts, but on the purely animalistic principle of the right of the strong, and the privilege of the predator to consume everything within reach.

In accepting the Cecil B. DeMille Award at the Golden Globes, Oprah Winfrey told the story of Recy Taylor, a black woman who died 10 years ago at age 97.

On her way home from church in 1944, six white men abducted and raped her. Her attackers threatened to kill her if she reported the incident, but Taylor, despite her fears, went to the police. Her efforts proved futile and the men were never brought to justice.

Oprah ended her speech on an optimistic note, saying that now, in part because of the #Metoo movement, what happened to Recy Taylor could never happen again. That might be true in the U.S. — but in Russia?

How many Russian women have stories of being raped at work or at home? Millions.

How many have memories of a vile man pushing his horrible body on them, holding his hand over their mouth and working his way into them with his jellylike flesh?

How many of my female colleagues who covered the war in Chechnya remember the horror of having to pass through a federal military checkpoint or finding themselves alone in a hotel room with a local macho character in some place like Nazran?

I am grateful to former State Duma Deputy Alik Osovtsov who pulled one such fighter off me — a soldier who was convinced that every female journalist from Moscow wants nothing more than to surrender herself to a Chechen.

But the problem is bigger: When I came to work at Izvestia as a 21-year-old, my colleagues, some of Russia’s best male journalists, placed bets on who would get me in bed first.

None of them succeeded, and my refusal to permit the chief editor to compliment my neck or chest caused me considerable problems at what was one of the Soviet Union’s leading newspapers.

Little has changed since then. Of course, at 59, age has solved the problem for me, but the male banter still focuses on women “pursuing their careers from the bedroom to the boardroom.”

This is because almost all Russian men — even the most liberal and intellectually developed — are convinced that a woman’s sex appeal will get her further in this world than her brains.

Yevgenia Albats is the chief editor of The New Times magazine, where a version of this article was first published. The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.