This is my eighth World Cup, and the main thing I’ve learned is that the most memorable moments are always away from the football, usually in someplace you will never visit again — Sapporo in Japan, the Amazon River in Brazil. What will stay with me from this World Cup is provincial Russia. Flying around the country, I glimpsed lives that I hadn’t known existed, and that nonetheless felt remarkably familiar.

For someone who spent a year once learning intensive Russian but has forgotten almost all of it since this may have been the easiest month in history to travel to Russian provincial cities. Say what you like about big tech companies, but I couldn’t have done it without Yandex and Airbnb. Yandex’s English-language taxi app means no more haggling with drivers in your 100 words of Russian. And Airbnb brought me into charming, impeccably-kept homes inside peeling Soviet-era apartment blocks around Russia, helped by the fact that just for this month, the hosts didn’t seem bothered about registering me with the authorities.

I stayed in five Airbnbs. All my hosts were women, aged under 40, who spoke good English and were taking the opportunity to monetize homes that no foreigner might ever need again.

My first host was a medical student who lived in a suburb of Volgograd, in an apartment building for which she apologized the moment she saw me. She told me about her time studying in Montenegro, and her treasured biannual trips abroad. I’ll never see her again, but I left feeling that she was an internationally-minded person who wanted much the same things from life as I do, except that her chances of getting them were much slimmer.

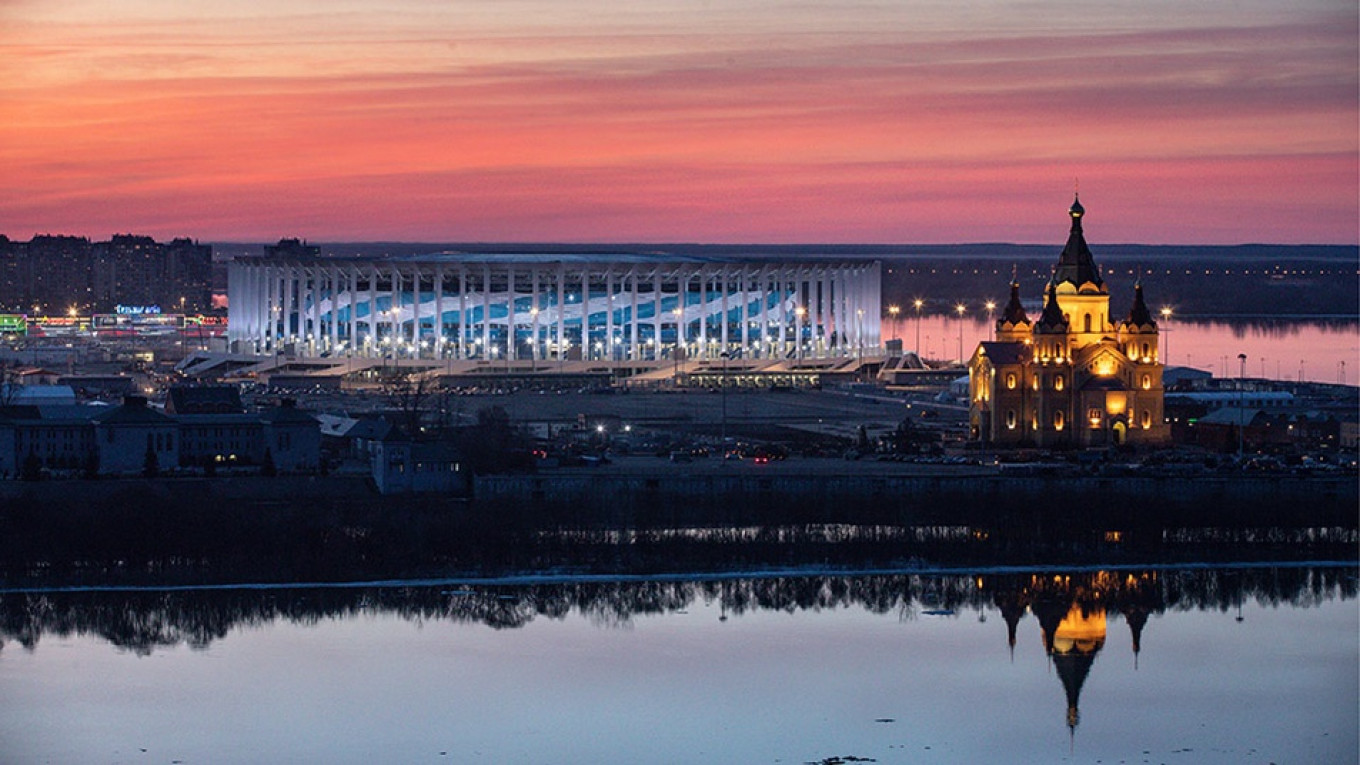

It was an experience I kept having. My hostess in Nizhny Novgorod, thousands of miles and hefty visa requirements removed from Paris, was studying French. The next day in Nizhny, a middle-aged woman came up to me and spoke impeccable English. I asked her where she had learned it. She taught English at the local university, she replied. I later calculated that she must have learned it in Soviet times when Nizhny was a closed city to foreigners. The day we talked, England played Panama in the local stadium (now already a white elephant, like most built for the World Cup). The game brought possibly the largest influx of English-speakers ever to visit Nizhny. I hope some of them will come back. I especially hope I will come back.

Russians who couldn’t speak English showed me constant acts of kindness. In Samara, where my Airbnb hostess was away, her mother mutely presented me with a specially made jar of her apricot jam. Sadly, I couldn’t take it on the flight.

The town I will remember best is Kaliningrad — German Königsberg until 1945. The cathedral where Immanuel Kant is buried lies in a pleasantly landscaped park. Wandering the lanes and lawns, I suddenly realized: I’m walking on top of what used to be downtown Königsberg. In the park, and in various local museums, you can admire lovingly presented black and white photo’s showing the electric trams that ran through this spot in the 1880s, the swinging cafes of the day, the German kids playing on the streets. Kaliningrad was once a place of Soviet triumph: the central square, which in the last years of Königsberg was Adolf Hitler Platz, has been renamed Ploschad Pobedy (“Victory Square”. But lately Kaliningrad has also become a place of sad remembrance. This was once a great, rich, beautiful, connected European city, a kind of Hamburg or Amsterdam. Many locals now mourn that lost place.

Meeting these provincial Russians yearning for the outside world, I kept being reminded of “Three Sisters.” In Anton Chekhov’s play, the sisters in their garrison town forgotten by time long for Moscow. One of them laments, “In this town to know three languages is an unnecessary luxury. It’s not even a luxury, but a sort of unnecessary addition, like a sixth finger."

Or again: "I don't think there can really be a town so dull and stupid as to have no place for a clever, cultured person. Let us suppose even that among the hundred thousand inhabitants of this backward and uneducated town, there are only three persons like yourself. It stands to reason that you won't be able to conquer that dark mob around you; ….their life will suck you up in itself, but still, you won't disappear having influenced nobody; later on, others like you will come, perhaps six of them, then twelve, and so on, until at last your sort will be in the majority.”

That is now happening. Clever cultured provincial Russians are still thwarted, and they may never again get to see Mexicans dancing on their local streets. But at least now they are like the three sisters with internet.

Simon Kuper is a Financial Times columnist. The views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.