I come from a standard middle-class family: my father was the director of a pension fund; my mother was a stay-at-home mom while we were young, but she had a law degree and went back to work later. I have two brothers and a twin sister. Everyone went to university.

I was the black sheep in the family. I barely made it through high school. I grew up in Amsterdam in the late 1960s, at the center of the student movement. When I was 14 I joined the Marxist-Leninist Center of the Netherlands, which turned into the Marxist-Leninist Dutch Communist Union Movement. I was a 14-year-old Maoist.

After graduating from high school at age 18, I decided to join the revolution. But the revolution was far away in Latin America and Africa. The only revolution close by was in Northern Ireland. I told my parents I was going there to study, but as soon as I landed, I took the train to Belfast and got very involved.

Red Pen

There were no Dutch correspondents there, so I called Dutch radio and television stations and said “I’m here.” One small broadcasting company said, “Why not?” At age 19, I became a correspondent.

I wrote for the Red Tribune. It drove my parents crazy. My mother saw the humor in it, but my father definitely did not. He thought it was a disgrace.

By the time I came back to the Netherlands people knew me from radio and television. Then I was a war reporter for many years — Vietnam, Cambodia, Angola, Mozambique, South Africa, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Beirut. After I met Ellen and we got married and had a son, I said, “Enough risky stuff.” But I didn’t want to stay in the Netherlands. It’s a great place, but it’s a bit boring and very small.

In 1988 when I was the editor of a magazine, some people visited from the Russian Union of Journalists. They were very nice and very excited about everything. They said, “Why don’t you come to Russia and start something with us — a magazine?” I called my wife and said, “Ellen, I want to go abroad.” “Where?” “Moscow.” Silence on the other end of the line. “Can’t we go to New York?” And that’s how it began.

The Romance of Russia

I found a very small apartment, and Ellen came with our infant son. It was 1990 and there was nothing in the stores — no diapers, no milk. We quickly found the Beryozka hard currency store. But my wife is also an adventurous person with a great knack for languages. In the courtyard with our son she quickly learned Russian by talking to the other moms. Ellen was a correspondent for another newspaper at the time, and one of the first interviews she did was with Vladimir Zhirinovsky — before he was Zhirinovsky. I remember the photos she took in his small flat, sitting on the bed interviewing him.

Moscow Magazine was the joint venture. Everyone loved it, but it was losing money. My boss at home pulled out, and we could have left then. But the spirit in Moscow was one of hope and expectation. Everyone was making plans and thinking about the future — and everyone was so kind to us. We stayed.

Newsletter to Newspaper

First we put out the Moscow Guardian — it was like a newsletter made on a copy machine, for the growing foreign community. It was a try-out for The Moscow Times. We thought: This might be something. It might work.

Ellen and I sold our house in Amsterdam and got a Dutch friend as our partner. We didn’t think about plans. We were young and excited to be making our own newspaper and reporting a story that became bigger and bigger. It was 1992, there had just been a coup — and to have your own newspaper reporting on this!

Journalism

Societies with a free press are more successful than societies without one, because the media challenge the powers that be. That’s good. Good journalism keeps society sharp.

Today everyone can make fake news. I think journalists didn’t realize fast enough what the technology had created. They thought, “It’s only the internet. We have our newspaper and we’re authoritative.” They didn’t understand fast enough that technology is leading and journalism is running behind. It’s a huge problem.

The other problem is that journalism is getting more and more sensationalist to pull in readers. But I believe there is still room for serious journalism.

Tighter, Looser, Tighter Again

When we were publishing Moscow Magazine at the Union of Journalists, there was a censor and a woman with the key to the copy machine. Then under Yeltsin, it was “anything goes.” You could walk into the KGB building and ask for anything. I went in and asked for the files on Dutch communists. They said, “Come on in and look for yourself.” That was probably the most unbridled period of freedom of the press in history.

This could not last. In any normal organized society you have to have a couple of rules, and for media, too. But even under Yeltsin real journalism in mainstream media never took hold. There was no market for investigative journalism. In the end the media quickly became a tool — one television station was used by the liberals, the other by the communists, and so on.

But the whole idea of journalism is that it isn’t anyone’s tool. That’s why Vedomosti became such a big success. It was the first Russian newspaper that was above it all, and not in anyone’s hands. Everyone predicted that it would be a big flop, and in the first weeks people criticized it for being too dry and objective. But that was exactly what we wanted.

Now we’re in a very difficult phase. I believe it was too wild, and now in my view it’s too tight. But journalism will open up again.

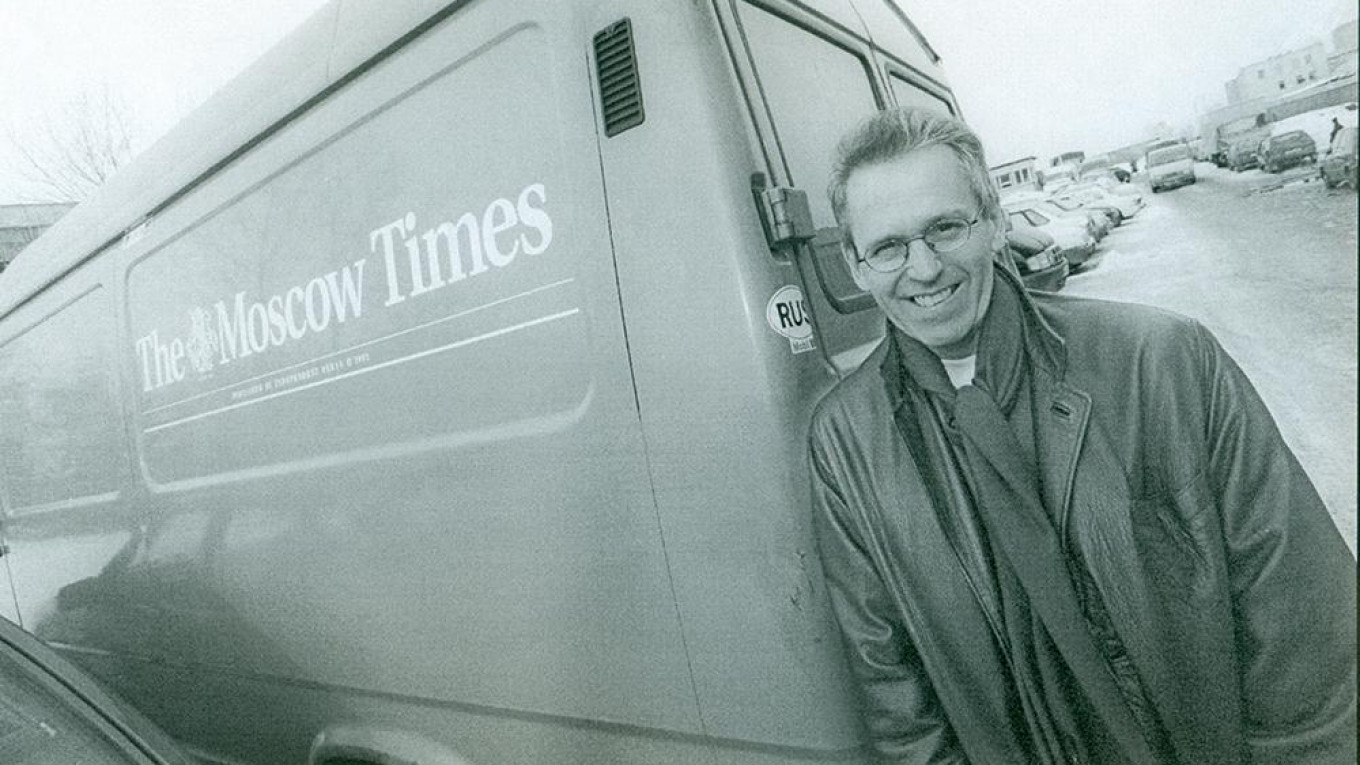

The Moscow Times Today

There aren’t so many expats in Moscow now, and with modern technology, they don’t need The Moscow Times as a lifeline. But the complexity that is Russia has remained. People are very curious about the context — what is going on and why — and that is where The Moscow Times still plays a crucial role. We’re based here, we live here, we have a unique network, we understand the country better than most people and we can report stories that won’t make it to other outlets. That’s our job and our challenge.

Looking Back: Gaffes and Triumphs

We got on the internet pretty early — in the late 1990s I spent millions on a Yahoo-like portal. But the market wasn’t ready for it. And then a friend, Yuri Milner, called me and said, “Derk, I’m going to start a new company. You want to join?” The investment was about $100,000-200,000. But I said, “Yuri, you’re calling at a bad time. I just lost a couple of million. To be honest, I’m kind of fed up with the internet.” That company became Mail.ru. Milner is one of the top ten internet investors in the world, the guru of digital and one of the richest people in the world. I could have been a billionaire by now!

I’m proud of two projects in particular. One is Vedomosti, because it added something to journalism in Russia. And Cosmopolitan is an amazing story. My wife Ellen was editor, so it was great to work on it together. Apart from its amazing commercial success, it really changed the lives of many women. We organized a lot of conferences and events, and women would come up to me and say, “You changed my life. I threw out my husband!” Cosmopolitan was the first publication to discuss subjects like abortions or domestic violence. It was emancipating. I was an activist but I became a journalist.

That is my mission here — not to judge, but to inform. “To inform and inspire” — that was the first slogan of Independent Media. It’s more important to give the background, the context, the effects of something instead of judging it. I think that’s the contribution I can make here. Through all the publications I was involved in — The Moscow Times, Vedomosti, Cosmopolitan and later RBC and many others — hundreds of journalists have worked for us and many have at least been touched by this philosophy of journalism. It’s a drop in the bucket, but it’s better than nothing.

..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Interview by Michele Berdy.

*This article is part of The Moscow Times' 25th anniversary special print edition. To view the entire issue click here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.