MOSCOW – On a sunny Sunday afternoon, a flow of voters made their way to polling stations across the Russian capital to take part in the final day of voting in the 2024 presidential election.

At 12 p.m. local time, thousands of Muscovites went to schools being used as voting stations to show their opposition to the election, which is believed to be rigged in the absence of a viable opposition candidate.

The Kremlin seeks to use the 2024 election to signal that Russians are behind President Vladimir Putin and his two-year invasion of Ukraine after wiping out all genuine challengers to his rule.

On Sunday, people who oppose Putin's candidacy stood in long lines to cast their votes in both Moscow’s city center and residential areas, as seen by a Moscow Times reporter. Some of them were smiling.

“Well done, I didn’t expect so many people,” said one Muscovite, who came to a polling station on Sunday, reflecting on the scale of the opposition movement in Russia.

Putin, who has led Russia for 24 years, is expected to win his fifth term when the polls close on Sunday evening, making him the longest-ruling Russian leader since Catherine the Great.

Running against Putin are Vladislav Davankov of the New People party, Leonid Slutsky of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDPR), and Nikolai Kharitonov of the Communist Party.

Though the registered candidates differ in political views and presidential platforms, all are widely perceived as backed by the Kremlin.

“I'm sure they will falsify everything to ensure Putin wins,” said one Muscovite, speaking on condition of anonymity due to the risks associated with openly discussing politics.

Others, however, expressed their readiness to vote for the incumbent president.

“If not Putin, then who?” a pensioner in her 60s told The Moscow Times, repeating a popular phrase among Kremlin supporters.

Nevertheless, with the election’s outcome believed to be certain, the Kremlin appears to be focusing on galvanizing voter turnout to demonstrate the public’s support for Putin.

In an apparent attempt to attract more voters, the election is for the first time being held over three days, while online voting has been implemented in 29 regions of Russia — a practice experts warn could be exploited for voter fraud.

Some Russians working for the government and state companies appeared to have been pressured to vote and asked to come to the polling stations on the first day of the election to demonstrate a high turnout — which is a violation of Russia’s election law.

One person who works for a state company in Moscow told The Moscow Times that the employees of her company were asked to vote electronically “before Friday at noon” and report it to their superiors in an online chat.

Footage from one polling station in central Moscow showed a queue of people who decided to vote on Friday afternoon. Russian media reported that Defense Ministry employees had been assigned to that particular polling station.

Similarly, in St. Petersburg, “there were signs that people were asked to vote on Friday morning,” a local election observer told The Moscow Times.

“There were many voters at our polling station who seemed to have come at the request of their workplaces and appeared to be colleagues who knew each other,” the election observer said.

According to independent election expert Roman Udot, who analyzed the turnout data from the first two days of the vote, election commissions across the country "manipulate" turnout to show higher results.

Two Muscovites said they were specifically asked to vote using the online system, which is available to approximately 38 million voters.

Critics say the online system makes it easier to rig the results and is “used mainly in regions that are problematic for the authorities.”

“[The online voting] is a black box,” said Stanislav Andreychuk, co-chair of the independent election watchdog Golos. “We do not know how the system works and where the numbers that it shows come from.”

Experts suggest that a significant voter turnout and a large percentage of votes in favor of Putin would be seen as endorsing the war and showcasing national unity in a country where most opposition figures have been either exiled or imprisoned.

Two anti-war presidential hopefuls, Boris Nadezhdin and Yekaterina Duntsova, were banned from running — and there is minimal independent oversight of the voting process.

To protest, some Russians intentionally spoiled their ballots or voted against any candidate other than Putin.

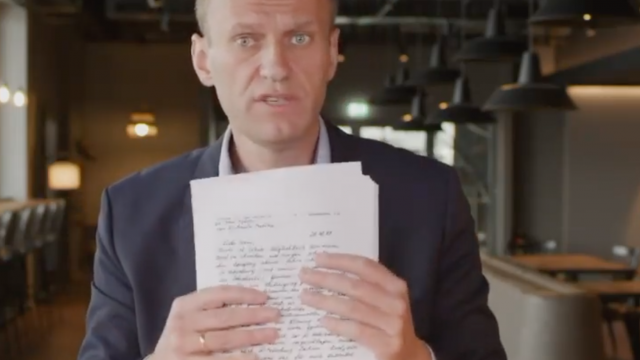

Late Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny, who died a month ago in an Arctic prison, and his allies also called on Russians inside the country and abroad to go to the polling stations at noon on Sunday, in the only legal form of showing resistance to Putin’s rule.

Moscow authorities threatened criminal charges against those who take part in election-day rallies, pointing to Article 141 of the Criminal Code, the obstruction of elections or citizens' electoral rights, which is punishable by up to five years in prison.

Activists in Moscow and across Russia also received warnings from the authorities against “certain actions during the election period... which may create conditions for the commission of illegal activities.”

Maria Andreyeva, the wife of a mobilized soldier, received a warning from Moscow prosecutors after she reposted a video promoting the noon demonstration which stated that the protest contained "signs of extremist activity.”

“I view this warning as interference and pressure on my electoral freedoms," Andreyeva, who is one of the leading activists demanding the return of 300,000 mobilized men from the war, told The Moscow Times.

Andreyeva said Russians “have to go to the polls” and “to ensure that our voice, the voice of every citizen of the Russian Federation, is used to the maximum in a form that corresponds to the will of a person, and not in a form in which it is convenient for the authorities.”

Despite the pressure, footage from several Russian cities — including St. Petersburg, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Yekaterinburg and others — and abroad showed thousands of people standing in long lines at polling stations.

In Russia’s regions neighboring Ukraine, like Belgorod, local authorities reported a high turnout of 77% as of Sunday afternoon.

"My friends and my whole family in Belgorod decided not to go to the elections because of the shelling," said Daria, 32, from Belgorod.

"Dad was going to go. But yesterday when he was driving in the city the explosions started. My parents are elderly people, their nerves are no longer the same. We decided it wasn't worth leaving the house."

In other regions of Russia — like the republic of Chuvashia — fewer people appear to be standing in the noon protest.

"Of course I was upset. But I realize that in the regions... it's riskier to participate in protest actions," said Maria, 30, from the city of Cheboksary in the republic of Chuvashia.

"But I was inspired by the photos of lines in Moscow and St. Petersburg that friends sent me. There are still a lot of us,” she said.

“And that gives me hope.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.