Moscow could not have wished for a better friend than Abe Shinzo. After returning to office in December 2012, Japan’s longest-serving prime minister pioneered a “new approach” to relations with Russia.

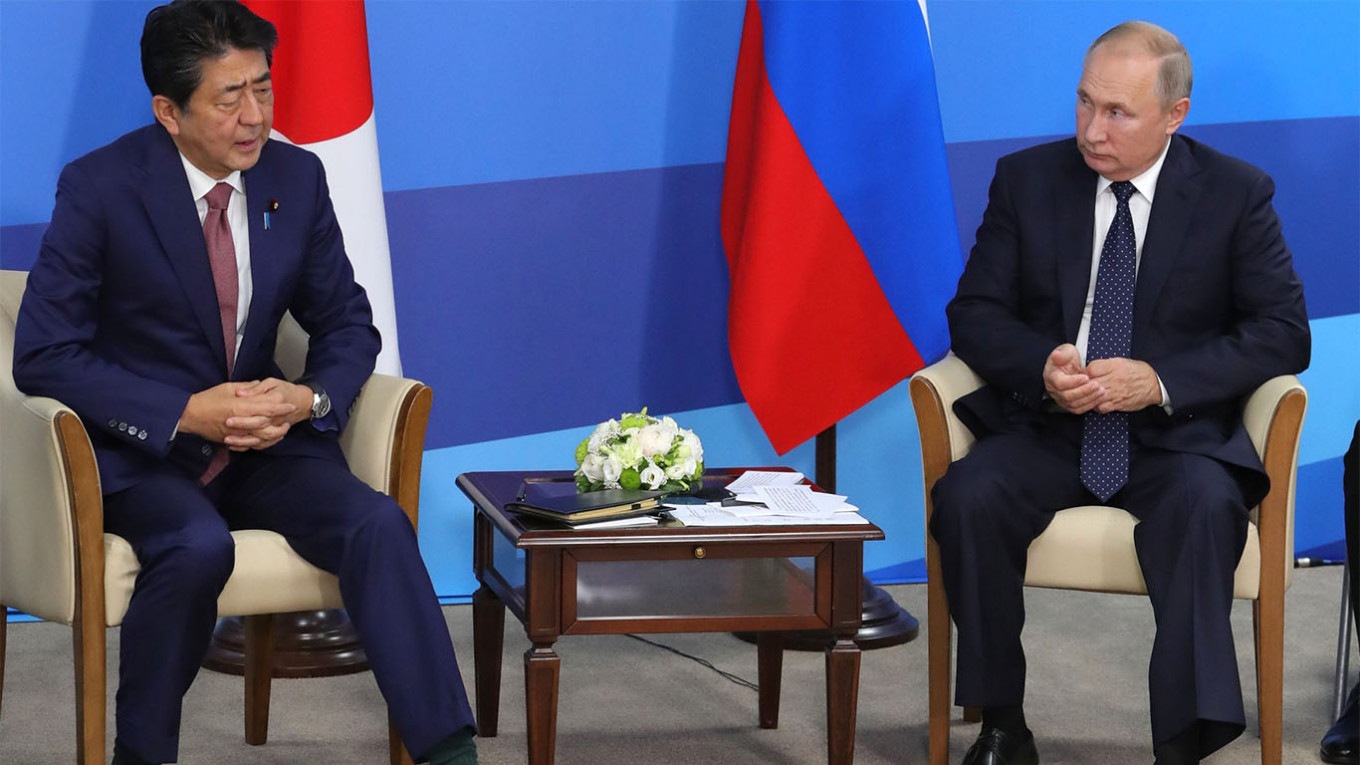

While no Japanese leader had made an official visit to Russia during the preceding decade, Abe visited 11 times between April 2013 and September 2019. He also promoted economic ties via an 8-point economic cooperation plan and was a prominent supporter of the Vladivostok Eastern Economic Forum, attending four times in a row. Russian citizens benefited too through an easing of Japanese visa requirements.

Additionally, Abe risked the ire of Western partners by refusing to join efforts to isolate Russia. Japan did introduce some sanctions after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, yet they were designed to have no impact. Despite major pressure from the U.K., Abe also refused to join the 29 countries that expelled Russian intelligence officers in retaliation for the attempted murder of Sergei Skripal in Salisbury in 2018.

Abe’s enthusiasm for relations with Russia was driven by three factors. First, he wished to secure his political legacy by resolving the territorial dispute over the Russian-held Southern Kuril Islands and concluding a formal peace treaty.

Second, Abe sought to ensure stable relations along Japan’s northern frontier so that Tokyo could concentrate on the threats of China and North Korea. In addition, Abe hoped to encourage Moscow to differentiate its interests in East Asia from those of Beijing.

Third, in a political system in which dynastic ties are strong, Abe was aiming to fulfill the ambitions of his late father, Abe Shintaro, who served as foreign minister (1982-86) and whose dying wish was to normalize relations with Moscow.

The identity of Abe’s successor will not be confirmed until mid-September. Yet, it is already clear that none of the leading candidates — Suga Yoshihide, Kishida Fumio, Ishiba Shigeru, Kono Taro — will pursue ties with Russia with the same eagerness.

For a start, the new leader will lack the same family-inspired commitment to the relationship (although Kono Taro’s grandfather did negotiate the agreement that ended the state of war between the Soviet Union and Japan in 1956).

More importantly, the next prime minister will not want to waste political capital on a foreign policy that came to be seen as a fiasco. This is because Moscow completely refused to reciprocate the concessions made by Abe.

On the territorial dispute, Abe indicated that he was willing to go beyond his predecessors and to settle for the two smaller of the four islands, representing just 7% of the total disputed landmass. He appeared to make some progress when he secured Putin’s agreement in November 2018 to base talks on the 1956 Joint Declaration, which promises the transfer to Japan of the islands of Shikotan and Habomai.

However, despite this agreement, Putin proceeded to include a clause banning territorial concessions in the constitutional amendments approved in July 2020. In Japan, this was taken as proof of Putin’s bad faith.

Similarly on security issues, in spite of Abe’s efforts, Russia continued its steady slide into becoming China’s junior partner. This culminated in the first Sino-Russian air patrol over the Sea of Japan in July 2019, which ended with a Russian aircraft violating Japanese-claimed airspace over the island of Takeshima.

Lastly, Putin could not resist the urge to subtly humiliate the overly zealous Japanese leader on a number of occasions. When Abe invited Putin to visit his hometown in December 2016, the Russian president arrived 3 hours late. In September 2019, Putin also chose the moment of Abe’s presence in Vladivostok to oversee the formal opening of a fish factory on the disputed island of Shikotan. Putin even rejected Abe’s offer of a puppy in 2016, only to subsequently accept dogs from the leaders of Turkmenistan and Serbia.

Japan’s new leader may say that they will continue Abe’s policy of engagement with Russia, after all they will represent the same political party. The reality, however, will be different.

The eagerness to travel frequently to Russia and to host Russian leaders in Japan will cease. Tokyo’s efforts to encourage Japanese businesses to invest in Russia will also slacken. On the territorial dispute, the next prime minister may also revert to actively demanding the return of all four islands. This is straightforward to do since Abe, while clearly signalling his willingness to accept only two, never officially dropped Japan’s claim to all four.

Internationally too, the next time Western countries come calling, Japan may be more inclined to join in condemning Russia’s foreign and domestic policies. This is especially likely to be true if the Putin-friendly Donald Trump is replaced as U.S. president by Joe Biden.

Overall, Putin came out on top in his relationship with Abe. He accepted the Japanese leader’s concessions but provided nothing in return. Yet, as so often with Putin’s foreign policy, short-term wins are a prelude to long-term losses.

With Abe, Russia had the opportunity to reinvent its relationship with the world’s third-largest economy. Instead, the Russian president has succeeded in alienating yet another country. What is more, a clear message has been sent to all leaders of the futility of seeking friendship with Putin.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.