Russian President Vladimir Putin’s assertion that liberalism has “outlived its usefulness” is less an expression of his deeply held convictions than a tactical device. In a world Putin believes to be fractured and adrift, he is looking for transactional relationships with people who hold similar views.

In an interview with the Financial Times ahead of the G20 meeting in Osaka, Putin objected to two aspects of what he calls liberalism: the embrace of immigration and the rejection of rigid, traditional values.

He described the lax immigration policies of German Chancellor Angela Merkel as a “major mistake,” and said U.S. President Donald Trump is right to crack down on the flow of migrants.

“Kill, rob, rape — nothing will happen to you because you’re a migrant and your rights need to be protected,” Putin said, according to a transcript of the conversation released by the Kremlin. “What rights?” he asked. “Break the law and you must be punished.”

On traditional values, he insisted he isn’t a homophobe, and then added: “They’ve invented, I don’t know, five or six genders already. I can’t even name them, I don’t know what that’s about. Let them all be happy, we have nothing against it. But we shouldn’t let that make us forget about the culture, the traditions, the traditional foundations of the families in which millions of indigenous people live.”

Putin’s cultural conservatism is consistent and sincere. In 2013, he approved a law banning the “propaganda of non-traditional sexual orientation to children.” But the legislation has been only weakly enforced, and it would be a stretch to say homosexuals are persecuted anywhere in Russia except Chechnya, where a fundamentalist Muslim regime enjoys strong autonomy.

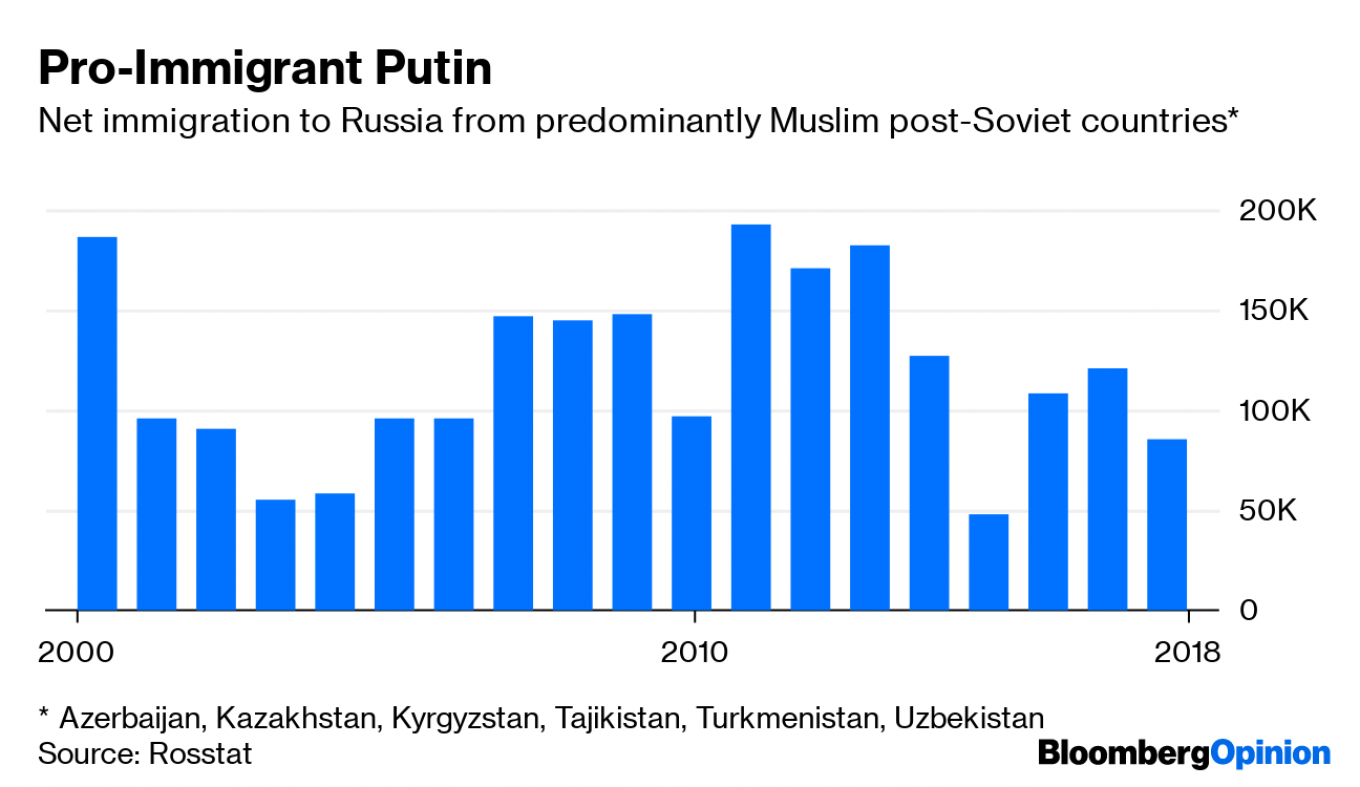

On immigration, however, Putin is, in practice, more liberal than most European leaders. He has consistently resisted calls to impose visa requirements on Central Asian countries, an important source of migrant labor. Given Russia’s shrinking working-age population and shortage of manual workers, Putin isn’t about to stem that flow, even though Central Asians are Muslims — the kind of immigrants Merkel’s opponents, including Trump, distrust and fear the most.

Putin told the FT that he saw these migrants as something of a problem, but “at least they all speak Russian.” He implied that his approach to migration differs from that of Europe's liberal governments. But the efforts he mentioned — teaching migrants Russian, or getting them to follow domestic laws and customs — are mostly in line with what the Europeans do, too.

Putin is an imperialist of the old Soviet school, rather than a nationalist or a racist, and he has cooperated with, and promoted, people who are known to be gay. He’s certainly not a liberal — he’s a convinced authoritarian — but he’s not far right or alt-right. So why is he saying things that, in the U.S. and especially in Europe, would put him in those camps?

One can conclude from the rest of the interview that this is transactional signaling. Putin clearly hasn’t given up on building a relationship with Trump (their jokey, jovial tone before their meeting in Osaka is proof that, despite all the difficulties in the U.S.-Russian relationship, the two hit it off on a personal level.)

He also appears to believe he can rebuild Russia’s relationship with the U.K. simply by moving on from the attempted poisoning of an ex-spy on British soil last year. Putin sees Trump, Brexiters, the European far right and alt-right as his natural allies against the established global order, one of steady alliances and stable multilateral organizations. He told the FT interviewers that he considers that world to be dead.

“It doesn’t look like any rules at all exist now,” he said, echoing his foreign policy brain trust’s assertion that the global system has failed and it’s every country for itself.

In other words, what Putin believes has outlived its usefulness isn’t the liberal approach to migration or gender, nor is it liberal economics — even though Russia has, in recent months, seen something of a shift toward central planning. It is the liberal world order. Putin wants to keep any talk of values out of international politics and forge pragmatic relationships based on specific interests.

Donald Tusk, the president of the European Council, appears to have immediately caught on to what Putin really meant.

“The global stage cannot become an arena where the stronger will dictate their conditions to the weaker, where egoism will dominate over solidarity, and where nationalistic emotions will dominate over common sense,” Tusk wrote in a press statement from Osaka. “Whoever claims that liberal democracy is obsolete, also claims that freedoms are obsolete, that the rule of law is obsolete and that human rights are obsolete. For us in Europe, these are and will remain essential and vibrant values.”

I doubt, though, that Tusk’s rebuke will resonate with Trump, the U.K.’s likely future leader, Boris Johnson, or indeed with some of the leaders on the European Council. Putin’s drive to put global politics on a more transactional basis isn’t easy to defeat; it’s a siren song, and the anti-immigrant, culturally conservative rhetoric is merely part of the music.

This article was originally published by Bloomberg.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.