The Biden administration’s April 15 announcement of new sanctions targeting the Kremlin and its perceived malign activities abroad was, first and foremost, an attempt to reset the U.S. sanctions strategy vis-à-vis Russia. Put simply, the Biden administration has moved to restore sanctions as a geo-economic instrument aimed at constraining Russian foreign policy adventurism, with both a signalling and an “offensive” component.

That is not to say the Trump administration took no meaningful action against Russia. Its 2018 black-listing of businessman Oleg Deripaska riled aluminum markets worldwide, pushing prices to a seven-year high. The Trump administration also imposed sanctions on the primary market for Russian sovereign foreign currency debt, a precursor to the key action in the Biden administration’s latest round of sanctions

The key difference between the Trump and Biden administrations’ respective sanctioning acts has been the messaging used to deliver them.

Biden’s team telegraphed for weeks that it was considering sovereign debt sanctions, which, if extended to the secondary market for such debt could have a devastating impact, even for a country like Russia whose liquid foreign reserves formally exceed its foreign debt.

In contrast, when the Trump administration implemented restrictions on Russian debt in August 2019, it did so in a highly confused and poorly explained manner. The move also came seemingly out of the blue, some nine months after a deadline for sanctions action required by the U.S. Chemical and Biological Weapons Act that Russia was found in violation of for its March 2018 novichok attack on former double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter in Salisbury, England, the aftermath of which killed an unrelated U.K. national.

At least nominally, the sovereign debt sanctions imposed in that action are more impactful than those taken by the Biden administration. The 2019 sanctions barred U.S. entities from participating in the primary market for Russian foreign currency debt, a market in which international players are traditionally more important than they are in the primary issuance of local currency debt, which the Biden administration has now banned.

Yet there was no concurrent attempt by the Trump administration to say what steps would incur further sanctions, including the sanctioning of secondary market trading in Russian debt. This despite the fact that the Trump team had shown itself willing to use precisely such sanctions, having barred the purchase of all Venezuelan government debt, as well as that of its state oil company, PDVSA, in May 2018.

While the Trump administration’s incompetence was legendary, its failure to signal any kind of Russia sanctions strategy appears to have been intentional. Its Venezuela actions were part of a coordinated ploy to raise pressure on the Maduro regime in Caracas, which included clear steps in the escalation of such sanctions, and US support for the Venezuelan opposition. It had the ability – and competence – to use sanctions as a signaling and escalatory tool when desired.

There was no such desire for Russia. In between finding Russia was responsible for the Salisbury attacks and the 2019 debt sanctions, the Trump administration agreed a deal with representatives of Deripaska to have sanctions on his companies lifted in exchange for adjusting the ownership structure of EN+ and Rusal, prompting much head-scratching about what, if anything, had been achieved.

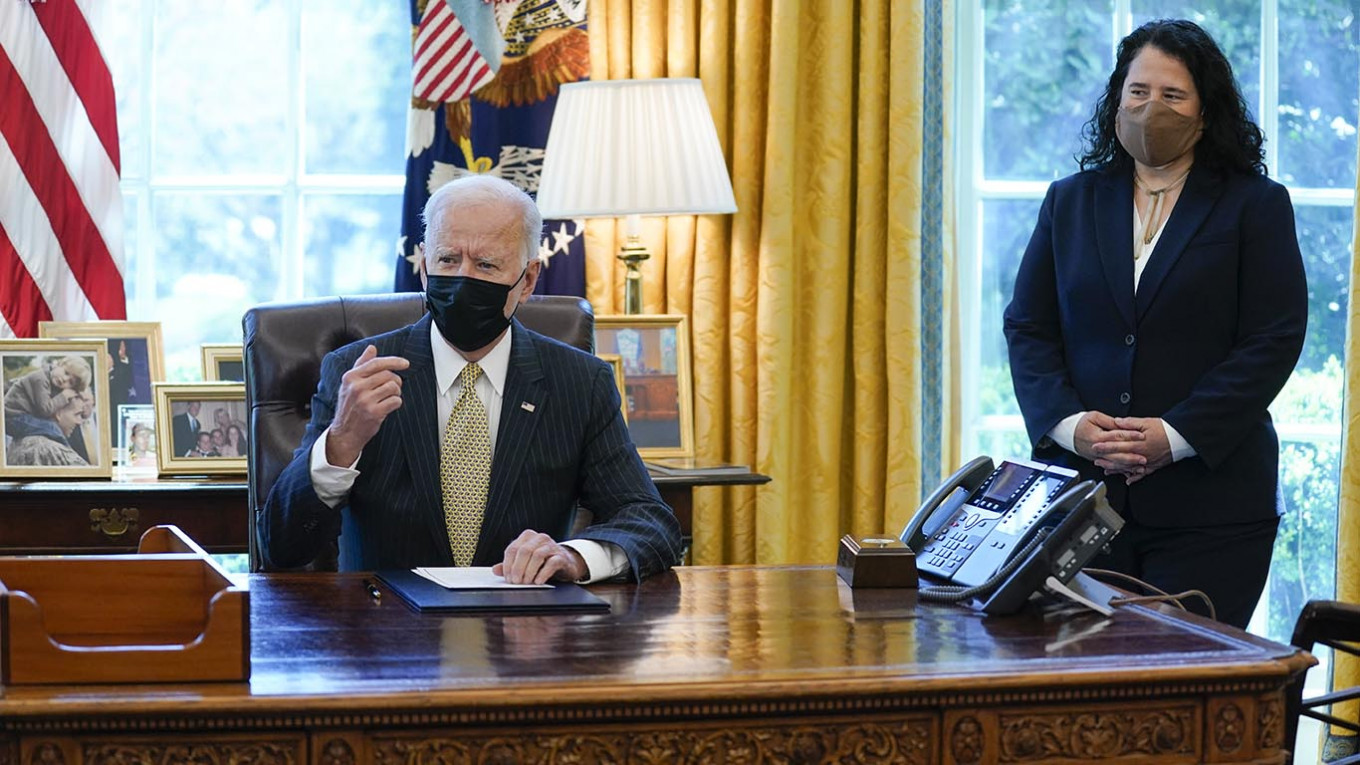

The Biden administration’s action, in contrast, came on the back of joint statements from NATO and the G7 regarding the buildup of Russian troops on Ukraine’s frontier, not to mention a statement from the State Department, a phone call between Presidents Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin two days prior and regular leaks to the press outlining the actions under consideration beforehand.

We have seen this before, when Biden was vice president under the Obama administration.

Debt-financing sanctions — Directive 2 of the sectoral sanctions — were the key innovation in the U.S. post-Crimea policy response to Russia. They were used to great effect in 2014 – precipitating not just pressure on the Russian rouble throughout the early months of the crisis but forcing the Central Bank and Rosneft to essentially mortgage national wealth in December of that year to enable the state run oil company to pay off its foreign bank loans, pushing the rouble to then-record lows.

The Obama administration also repeatedly tightened the permissible maturity of short-term debt to companies affected by these sanctions such as Rosneft, making the sanctions more strenuous without introducing new measures as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continued.

Threats were still made to cut off Russia from Western capital markets while Trump was president, they merely emanated from Congress, which in 2017 passed the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) that further tightened the maturity limits on firms affected by these sectoral sanctions. The Senate threatened to go further with an outright ban on Russian sovereign debt in the proposed 2018 Defending American Security From Kremlin Aggression Act (DASKA), though it never passed.

Russia has built up its reserves against such actions, including through some bond contract language finesse it has shown remarkable expertise for in recent years. Nevertheless, the Biden administration is correct to believe that the threat of such sanctions action will factor into Kremlin foreign policy decision making, as even if Russia can “afford” the move,it risks rupturing any hope of improving, or even stabilizing, Russian-Western relations for the foreseeable future.

Direct challenge

The sovereign debt sanctions were, of course, not the only sanctions act the Biden administration implemented.

It also blacklisted six Russian technology firms, expelled 10 diplomats, sanctioned dozens for attempting to interfere in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, and named-and-shamed Russian entities found responsible for the SolarWinds hack. However, the steady expansion of U.S. Treasury blacklists under the Obama, Trump, and now Biden administrations appears to have had a limited effect on US policy goals, whether it be in Myanmar, Syria, Venezuela, or Russia.

The Biden administration appears to be betting that debt financing sanctions, and the threat of further such measures, can again be more effective. The Trump administration, despite its record-setting pace of sanctions, did not touch the Directive 2 sectoral sanctions, except when ordered to amend them by CAATSA, nor did it make any additional Russian entities subject to them.

If one believes money is power, debt financing sanctions are a direct challenge to Moscow given that debt is the ability to move money over time.

The Biden administration appears set to return to this battlefield in hopes of constraining Russian foreign policy adventurism, deterring cyber and election-interference activity, and perhaps even in hope of keeping jailed Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny alive.

Time will tell.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.