Russia and Ukraine on Saturday swapped 35 prisoners each, including filmmaker Oleg Sentsov, 24 Ukrainian sailors and potential MH17 witness Vladimir Tsemakh, in a key step toward bringing an end to the war in eastern Ukraine that has claimed more than 13,000 lives since 2014.

Laden with wide-ranging implications, the move underlines new Ukranian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s commitment to his campaign promise to end the conflict in the Donbass region between government forces and Russian-backed separatists. It also is a signal from the Kremlin to the European Union that it is willing to play ball, political analysts say.

“This is the most logical way to start peace talks,” said Andrei Kortunov, director general of the Russian International Affairs Council, a research group set up by the Kremlin. “And with Sentsov included in the swap, it represents quite a significant step by Moscow.”

Rumors that a prisoner swap between Moscow and Kiev could be in the works swirled all summer. And after Ukraine freed Russian journalist Kirill Vyshinsky from pre-trial detention last week, speculation reached fever pitch when Sentsov was moved from a prison colony above the Arctic Circle to Moscow the next day.

Zelenskiy, a former comic actor, and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin had been discussing the possibility of the move since mid-July. But the swap, which was expected to take place before Ukraine’s July 21 parliamentary elections, was delayed.

“Before the elections, Zelenskiy wasn’t taken seriously yet in Moscow,” said Konstantin Skorkin, a contributor to the Carnegie Moscow Center. “But once his party won with a majority, the Russian authorities realized they would have to deal with him in the long-run.”

“The trade is about a gesture of trust between the two countries, which is what was missing for the peace process to get underway,” he added.

On Thursday, Putin said the prisoner exchange would be “a good step forward toward the normalization” of relations between the two countries.

Zelenskiy, who welcomed Ukraine's returned prisoners at Kiev's Boryspil International Airport on Saturday afternoon, told journalists at the scene that he hoped the swap would mark the start of “the first chapter” in restoring relations between Russia and Ukraine.

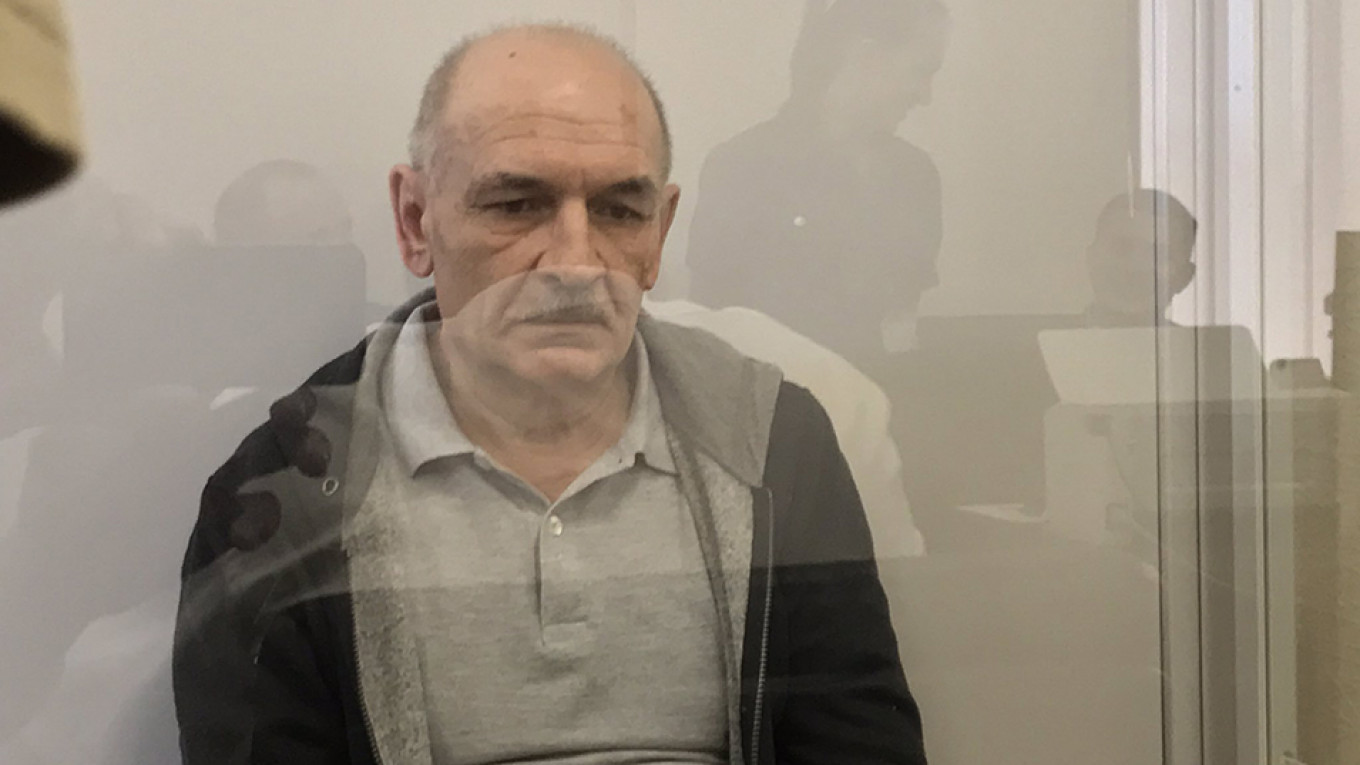

The trade, however, had been held up for another week over Vladimir Tsemakh, a potential key witness in the 2014 downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17.

Tsemakh, who was arrested by Ukrainian authorities in June, had been recorded on video saying that he commanded an anti-air brigade in eastern Ukraine and hid evidence of a Buk missile system. Dutch investigators say separatists used a Russian-made Buk missile to shoot down the Malaysia Airlines jet with 298 on board, most of whom were Dutch.

On Wednesday, a Kiev appeals court ruled to release Tsemakh from custody, to the disappointment of those still seeking justice.

“From the Ukrainian perspective, I understand this was a difficult decision,” Piet Ploeg, who lost his brother, sister-in-law and nephew in the crash and heads a Dutch foundation supporting the families of the victims, told The Moscow Times. “At the same time, the relatives of the MH17 victims are all very disappointed. We believe Tsemakh should have never been involved in this swap and that he should face the consequences of his actions.”

“With this move Russia is directly obstructing the investigation,” Ploeg added.

Zelenskiy faced criticism at home and in the European parliament over the inclusion in the swap of a potential witness in the MH17 investigation. On Saturday, Dutch foreign minister Stef Blok said that the prisoner trade had been delayed so that investigators could question Tsemakh before he was sent to Russia.

But for Zelenskiy, getting back all of the Ukrainian sailors, who had been held in Russia since November when Russia seized three Ukrainian naval ships as they attempted to pass into the Azov Sea through the narrow Kerch Strait off the coast of Crimea, ultimately won out.

Although Russia and Ukraine share territorial control of the sea, Russia has controlled access to it after building a bridge linking the Crimean peninsula, which Russia annexed from Ukraine in 2014, to its mainland.

In his first comments after winning the Ukrainian presidency in a landslide in April, Zelenskiy promised to secure the release of all 24 sailors. He also brought them up in his first telephone call with Putin in July.

But while getting back the sailors will be seen an important political win for Zelenskiy at home by some, it is Sentsov who is being seen as the biggest gesture of goodwill from Moscow.

A native Crimean, Sentsov, 43, was in his fifth year of a 20-year sentence in a penal colony above the Arctic Circle. Arrested less than two months after Russia annexed Crimea, Sentsov was convicted of setting fire to the unofficial offices of the ruling United Russia party and plotting to blow up a Lenin statue.

Sentsov said there was no evidence to back up the claims, while Russian human rights activists and much of the West believed the charges of terrorism were politically motivated.

Last May, ahead of the 2018 FIFA World Cup, which Russia hosted, Sentsov began a 145-day hunger strike to stir up an international outcry. In October, the European Parliament awarded him the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought.

Zoya Svetova, a human rights activist who appealed to Western leaders to help pressure Russia into releasing Sentsov, called the move a win for the Kremlin.

“It’s a plus for them because it shows that sometimes they can have mercy and hold a dialogue with society,” she said. “It may take five years of civil society pressure, but someone can indeed be freed.”

Svetova attributed Sentsov’s release to multiple factors, including his hunger strike which she said brought the attention of world leaders to his case.

Also bringing attention to the case, she said, were letters of appeal to French President Emmanuel Macron from her and Pussy Riot activist Maria Alyokhina that were published in the country’s Libération newspaper. She believes Macron played a role in Sentsov’s inclusion in the swap.

Last Friday, as speculation built over the possible trade, Macron spoke to Zelenskiy by phone, according to the Ukrainian president’s spokesperson, promising to hold peace talks in the so-called Normandy format, which involves the participation of France and Germany, in the near future. Zelenskiy had agreed the same with German Chancellor Angela Merkel a day earlier.

During the Group of Seven (G7) nations meeting in France last month, Macron made headlines for his calls to bring Russia and Europe back together, repeating what he had said during a meeting with Putin days earlier. Russia was expelled from G8 after annexing Crimea.

But after U.S. President Donald Trump called for Russia to be readmitted to the G7 group, a French diplomatic source told Reuters that progress had to be made in the Ukraine crisis for Russia to be readmitted.

Last Friday, Zelenskiy’s spokesperson wrote on Twitter that Macron also promised Zelenskiy that “it is impossible for #Russia to join the #G7 while it is still committing aggression in Donbas & occupying Crimea.”

Kortunov, who has been closely following the developments in Russia-France relations, said that the Sentsov release was certainly part of a wider discussion between Putin and Macron when they met in France last month.

“As part of a deal, Moscow would like for Kiev to remove the economic blockade of the Donbass,” he said. “And it would also be hoping for Europe to remove sanctions in the near future.”

Ultimately, how much Moscow will demand from Kiev in return for the swap is yet to be seen, said Skorkin, the Carnegie Moscow Center commentator. Nevertheless, he added, the move should be viewed positively.

“People are going home to their families — that’s what’s important,” he said. “Bad peace is better than a good war.”

Pjotr Sauer contributed reporting to this article.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.