(Bloomberg) — Late on Feb. 7 and early on Feb. 8, U.S. forces in Syria likely killed the greatest number of Russians since the end of the Cold War — more than 200 soldiers.

There will, however, be no international repercussions, nor will any of the Russians get posthumous medals like Roman Filipov, the fighter pilot who was shot down over Syria earlier this year and resisted capture until he was forced to blow himself up with a hand grenade.

The reason even the exact number of the dead will never be officially confirmed is that the Russians were mercenaries, not regular troops, and their mission likely had nothing to do with Russia’s geopolitical goals in Syria.

They were attempting to take over a refinery in the Al Isba oil and gas field in the oil-rich province of Deir-Ez-Zor, which formerly provided most of ISIS’s oil wealth in Syria. In a statement on the incident, the Russian Defense Ministry called them "Syrian militia members" conducting "an operation against an ISIS sleeper cell."

That makes it likely that they were on a purely commercial mission for the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, who needs access to the oil so he can rebuild the territories he controls — probably in exchange for a share of the oil business.

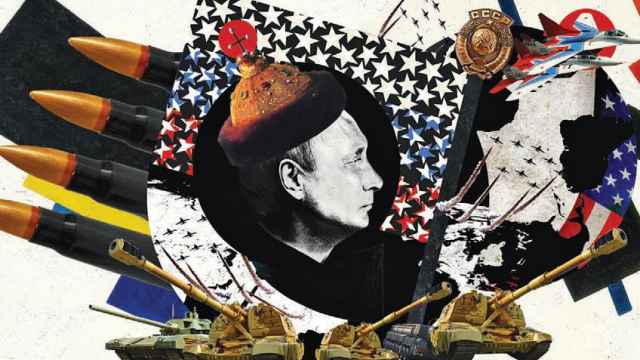

Russians are engaged in two wars today. One is being fought by regular troops for the geopolitical priorities of the Kremlin. The other involves mercenaries seeking commercial profit. The line between the two wars isn’t as blurry as it might seem. But there is, at times, a bit of an overlap.

The Syrian campaign has provided the clearest example of how it works so far. There are the official Russian forces, which have already celebrated victory and boasted about the combat experience they have gained.

Their goal was to save Assad’s regime while losing as few Russian military lives as possible (only 44 Russian service members have been reported dead), establish an increased presence for Russia in the Middle East, and make the country an official go-to force in resolving the region’s many crises.

And then there’s Wagner Private Military Company, an outfit based in southern Russia that hires able-bodied men, often ex-soldiers, as deniable boots on the ground for a salary that often exceeds what regular soldiers are paid but without the state-of-the-art equipment and official state support that regulars enjoy. The pay may come from the Russian government, but also from side projects, like taking over oil installations for Assad.

The regular troops and the Wagner irregulars have to fight on the same side: It helps advance the geopolitical agenda. But the degree of coordination between them is often low. In Syria, for all intents and purposes, Wagner is working for Assad, not Russia ("Syrian militia members").

This dividing line between the two wars is there both in defeat and in victory. If the refinery raid succeeded, only Assad would’ve celebrated. The reason information about Wagner losses leaks out and gets confirmed by multiple sources is that many of the men fighting in Syria also fought in eastern Ukraine.

That’s why Igor Girkin, former military commander for the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic, gets reports of fallen comrades, and how amateur investigators who track the Russian participation in the Ukraine conflict — such as the Conflict Intelligence Team or Ukraine’s Mirotvorets — confirm the names of some of the dead.

The situation in eastern Ukraine is similar to the one in Syria, but there’s more overlap between Russian regulars and irregulars. The Kremlin has clear geopolitical interests in the area — the destabilization of Ukraine — but it can’t be discussed openly.

President Vladimir Putin was cagey in his only comment on the matter, which came in a 2015 press conference. "We have never said that there are no people there who are involved in resolving certain issues, including in the military sphere, but that doesn’t mean regular troops are present there," he said.

Russia has never confirmed sending regular units in key moments of the east Ukraine war, though those operations are well-documented. Also present are Wagner and local irregulars, who fight out of nationalist convictions on one level and a share of the region’s mining wealth on another.

As in Syria, the Kremlin geopolitical interests and the irregulars’ commercial interests are not 100 percent aligned. But the irregulars can’t do anything that hurts the Putin agenda without facing a stiff punishment.

The outsized role of mercenaries in Russia’s conflicts isn’t just about deniability. It’s basically an extension of the freelancing culture that has thrived under Putin in Russia’s law enforcement agencies, with intelligence services using mobs and hiring black-hat hackers for odd jobs that hold the promise of side revenue.

For the official Kremlin — the side that wages the geopolitical wars — deniability is, however, the most important issue. And in the Deir-Ez-Zor case, it’s extremely difficult to maintain because of the sheer number of casualties.

The incident shows how allowing Russian irregulars into conflicts because they can be helpful to Putin’s agenda can get risky. Grigory Yavlinsky, a liberal who is running in Russia’s pretend presidential election, has demanded that Putin account for the Russian deaths.

More importantly, news of funerals and grieving families will circulate on the social networks — and many Russians won’t care about the private status of the fighters. They will, like Girkin and his nationalist allies, draw attention to Putin’s inability to respond to carnage unleashed on Russian citizens by the U.S. — the country now seen in Russia as its biggest enemy.

The returning mercenaries will also tell tales of official indifference: I doubt they fully understand how loose the ties are between them and the regular Russian military. In fact, they probably like to think they’re fighting a Russian war, not a private firm’s.

Even though that’s an illusion, it will contribute to slowly welling discontent with a regime that divides the fighters who do its dirty work into first-class and second-class ones. Essentially, it’s yet another case of the self-serving Putin regime failing ordinary Russians.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg View columnist, the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and the founder of the opinion website Slon.ru. The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.