Twenty years ago, Vladimir Putin appeared on the political Olympus in the guise of an effective bureaucrat with a security services background; a market-oriented statesman and pragmatist without ideological pretenses.

Today Putin is a powerful authoritarian leader of the “strongman” type, engaged in a political confrontation with the West and an ideological struggle with global liberalism, in the service of which he is decisively sacrificing any pragmatic goals for developing the country. And even when he speaks of modernization, the conversation turns fairly quickly to armaments.

Two eras

If Putin had left power in 2008, he would have gone down in history as one of Russia’s most successful leaders. After 15 years of crises and upheaval in the country, a relative stability had arrived under “managed democracy, but most importantly of all, a period of intense economic growth had begun — 7% annually on average — coupled with an even more impressive growth in per capita income.

Of course, cynics would have said that the reason for these successes was the rise in oil prices and the fact that the cycle of transformation was going through the recovery phase.

And a considerable number of skeletons had already built up in the closet of this successful government by then: The second Chechen war and its consequences, the YUKOS affair, the creation of legal and commercial hybrids in the form of state corporations, among other things. But in terms of historical memory, none of this could have outweighed the atmosphere of success, a wave which Putin would have ridden out of office.

The second half of Putin’s 20 years in power, 2009–2019, has been, to a significant degree. the opposite of the first.

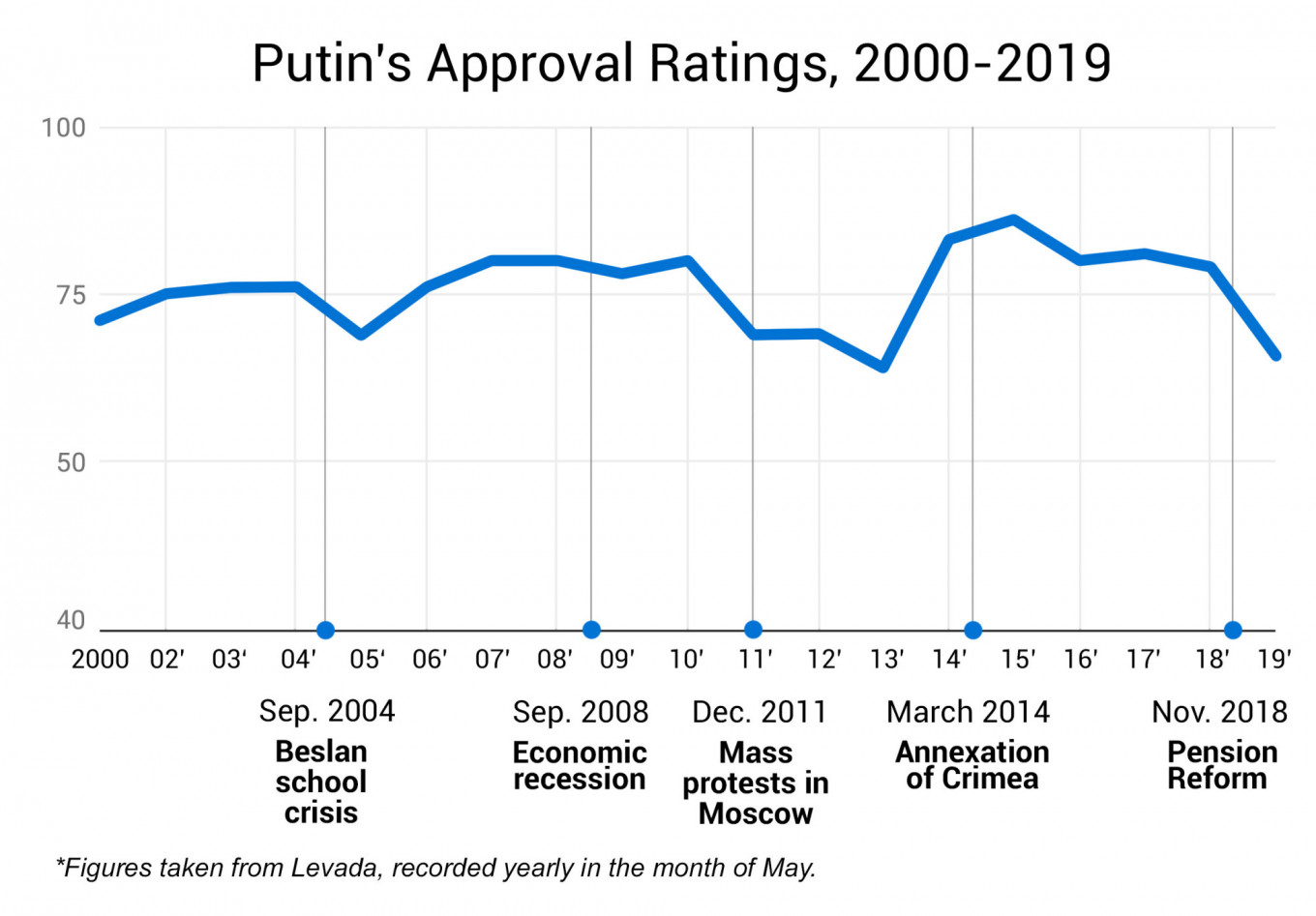

There have been two economic crises linked to the volatility of oil prices, in 2009 and 2015, and a political crisis caused by the Moscow protests of 2011–2012, the last of which turned the regime toward an authoritarian clampdown, the domination of the security elites and decision-making that reflected their logic.

This last circumstance created the trigger for the next crisis — a foreign one, linked to the annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine.

The decisions taken then were not compulsory and not the only ones available. But these decisions, which made the confrontation with the West the central feature for Russia, ultimately consolidated the domination of the security elites and silovik thinking in all spheres of state life.

And so, a series of economic, domestic and foreign crises — in 2008-2009, 2011-2012 and 2014-2015 — as well as three wars — in Georgia, Ukraine and Syria — form the main narrative of the second half of Putin’s rule. At the same time, average annual economic growth fell to 0.6 percent.

As a result, while in 2000 GDP per capita in Russia was 14.5% of that of the U.S. and 21.5% of the EU average, in 2008 it was 22.5 and 32% respectively, and in 2018 — 21.5 and 31%. This is stagnation, the inability to close the gap to the world’s economic leaders, despite the fact that the average annual oil price was $54 per barrel during the first period, and $74 in the second).

Total revisionism

Putin did not simply fail to leave in 2008. In fact, this was the point at which his goals underwent a decisive change. In 2000 he arrived with the grand objective of stabilization and depoliticized modernization, a goal he achieved with the means available to him within his competence.

During the second period his grand objective was the restructuring of the state political system, which was undoubtedly extremely volatile, that had formed as a result of the first post-Soviet decade.

The total revisionism of the second Putin period is linked to this. The change gave absolute priority to the understanding of ”sovereignty;” searched for new ideological pillars in the form of “social ties” and “traditional values,” pushed aside the imperatives of modernization and formed “nationally oriented elites.” It also refused to recognize the borders that had resulted from the collapse of the U.S.S.R., leading to a decisive turn away from cooperation toward confrontation with the West.

It is possible that all of this would have been a great success, if the emerging Putin system had demonstrated economic effectiveness, at least at a level comparable to that achieved in authoritarian Kazakhstan, whose per capita GDP was 10% of that of the U.S. in 2000, 18 % in 2008, and 20.5 % in 2018, almost level with Russia).

But the Putin system was unable to do this. And its successes in building “effective authoritarianism” in certain spheres of government cannot compensate for this fundamental fact.

In the end the objectives have turned into a naked sermon of anti-liberalism and anti-Westernism, a reevaluation of the “borders of the Russian world” — through the formation of a band of confrontation and distrust around Russia, and the building of a “nationally oriented elite” — into the absolute supremacy of the security forces and the powerful oligarchies, which constantly demand benefits, preferences and cash injections.

Putin is very unlikely to abandon his efforts to de-westernize Russia. And this fruitless, from a historical perspective, tug-of-war is likely to remain the defining characteristic of the final phase of his political career.

This article was originally posted by Vedomosti.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.