When an Aeroflot flight attendant sued the company for discrimination, she became an unlikely champion of body image issues in a society that has traditionally proven reluctant to embrace the overweight and the obese.

Yevgeniya Magurina, 41, and several of her coworkers at the Russian flag carrier said they were rotated off international flights and stripped of the cash bonuses that came with working these routes.

Their offense? Wearing size L or above.

“I’ve never felt so humiliated in my entire life,” Magurina told The Moscow Times. “They measured us like cows and took photographs. I was told my breasts were too big and that I need to wear a compression sports bra.”

Her case was ultimately dismissed in court. But all was not lost: by generating headlines, she and her colleagues turned the spotlight on body image and weight issues in Russia — topics that are rarely discussed publicly and that have not traditionally been treated as major health concerns.

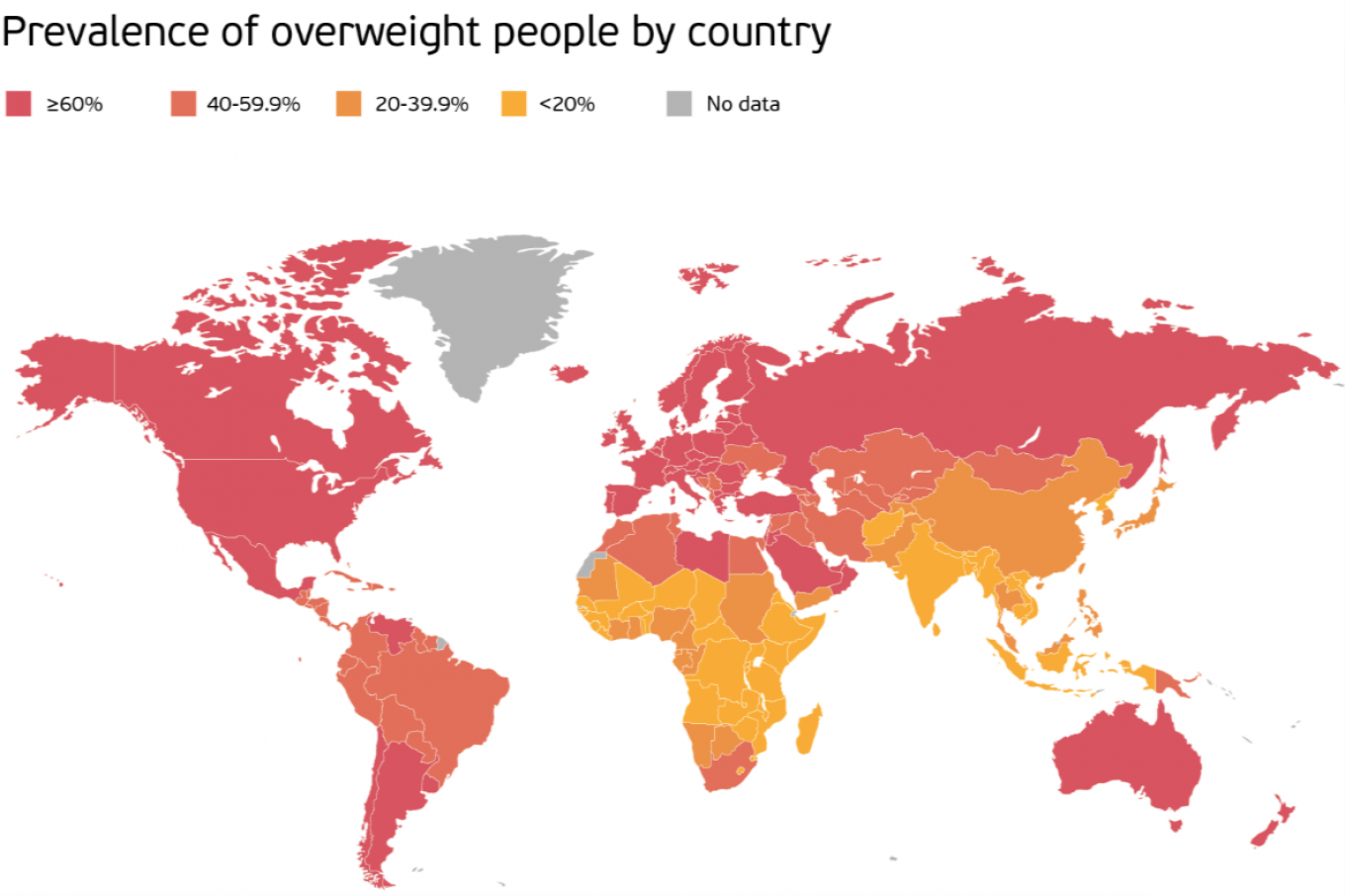

Despite typically being relegated to hushed conversations between friends, obesity and weight issues are a cause for concern in Russia. More than 60 percent of the country’s population is overweight, according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. Of those, some 20 percent are obese.

The problems surrounding these figures are multiplying. Over the past 15 years, the number of people struggling with body image issues has been growing exponentially because of the stigma surrounding overweight people, says Maria Belyakova, a Moscow-based psychologist who specializes in eating disorders and body image issues.

“We judge people by their looks. When we see a fit person, we automatically think they’re successful, healthy and accomplished,” Belyakova told The Moscow Times. “When we see an overweight person, we presume they’re unhealthy and have problems.”

Who is to blame?

Alongside the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Mexico, Australia, Argentina, Saudi Arabia and all of Western Europe, the WHO describes Russia as part of a group of countries with the highest rates of obesity.

Obesity in Russia is not as high as in the U.S. or Western Europe, says Dr. Joao Breda, who heads the WHO’s nutrition, physical activity and obesity program in Europe. But together with other eastern European countries, Russia is quickly catching up to the West.

Obesity in Russia is on the rise for the same reasons it is everywhere else. Mealtime traditions, outdoor activities and home-cooked meals are on the decline. People move less and eat more processed and junk food. Supermarket shelves are full of sugary foods. Consumption of fruit and vegetables is low.

In the absence of state recommendations, Russians’ ignorance about what they eat is harming them, says dietitian and gastroenterologist Ksenia Selezneva. Not only do unhealthy eating habits cause obesity — readily available diets either don’t work or are even more harmful. The fact that dietitians are rare in state and private clinics adds insult to injury.

“Several generations were brought up by people who survived post-war famine and the Soviet-era deficit,” Selezneva told The Moscow Times. “Our grandmothers were basically overfeeding their children and grandchildren.”

“When the rest of the world was figuring out what to eat in order to be healthy,” she says, “most of Russia was figuring out what to eat to survive.” Currently, more and more people are starting to care about nutrition influencing their health and turn to dietitians for help, but there is still a long way to go.

A look at Russians’ physical activity is another piece of that puzzle. Only 2-3 percent of Russia’s population have gym memberships, says Olga Kiselyova, head of the World Gym fitness centers chain.

The percentage is higher in cities — 12 percent in Moscow, 10 percent in St. Petersburg — and generally growing. But it’s lower than the West. “35 percent of New Yorkers have gym memberships. In Europe, the number is around 16-18 percent,” Kiselyova told The Moscow Times.

For years, Russia — like most other countries — didn’t consider obesity a disease, Dr. Breda says. The country’s medical specialists simply were not trained to deal with the issue and struggled to address it.

“They were focused on things that were actually killing people — cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes,” Dr. Breda told The Moscow Times. “Only more recently did health professionals make the connection between these and excess weight.”

Now, there is interest among Russian scientists in studying the issue more thoroughly and tackling the problem. But first of all, the stigma must be eliminated, Dr. Breda says. “We’re used to thinking that an overweight person is to blame for being overweight, that he or she can change out of sheer will power. We need to change that mindset.”

Body shaming a la Russe

When the court dismissed the flight attendants’ discrimination lawsuit against Aeroflot, the airline issued an unsympathetic statement in its defense.

Overweight flight attendants, it said, fail to properly perform their duties because they aren’t able to move swiftly throughout the airplane. The fuel needed to carry the extra weight costs the company more — 759 rubles ($13) a year per kilogram of weight above the norms set for flight attendants. Moreover, passengers prefer “young and thin” flight attendants — and Aeroflot could not ignore the “preferences of its customers,” the statement said.

“It is absolutely ridiculous,” Magurina laughs in response to the statement. “I’ve never been thin and I’ve worked as a flight attendant for more than a decade doing my duties just fine. Me and the girls joke that they’ve decided to crack down on ‘the fat, the old and the ugly.’”

Body image anxiety, unlike other psychological disorders, is closely linked to mass media and its influence, says psychologist Belyakova. The advertising industry and showbusiness force an impossible and ideal body type on an increasingly self-conscious audience.

A new body standard emerged five to 10 years ago, says Belyakova: “flat belly with curvy hips, butt and breasts.” It’s a body-type that can only exist in a fraction of the population, “but people look at it, compare it to their bodies, don’t like the results — and that’s where all the problems start.”

Unlike in the West, where body shaming a person for being overweight, obese, or unconventional in any other way, is frowned upon, it often openly happens in Russia.

Celebrities write tabloid columns about how unpleasant it is to “share an elevator, an airplane or a swimming pool with a fatty.” The self-styled “liberal” TV show host Kseniya Sobchak even wrote an Instagram post — to millions of her followers — saying that she “didn’t like fat people.”

This level of public discussion suggests that staying thin should be a top priority for women, overshadowing any other problems they might face.

“[Society thinks] the worst thing that can happen to a woman in Russia is not being deprived of education, or marrying an alcoholic, or even the danger of violence,” says Anna Svolochova, head of Body Positive, the biggest online self-acceptance online community in Russia.

“The worst is gaining weight and becoming a second-rate object.”

Not quite helping

It isn’t just Russia’s obesity rates that are catching up with the West. It is pop culture is too. In 2015, Russian entertainment TV channel STS launched its version of the famous U.S. reality weight-loss show The Biggest Loser. Several similar programs began to appear on other national channels too.

This isn’t such a bad thing in theory: These shows promote healthy lifestyles and encourage people to confront their weight issues. But their tone often contributes to the psychological trauma related to those issues, Svolochova says.

The popular reality show, I’m Losing Weight, which aired nationwide between 2013 and 2016 often addressed participants condescendingly. “Yelena was gaining weight, quickly losing her health and hope to ever find love,” the show host would say. “Our chief dietician could turn even 100 kilograms of fat into mouthwatering female curves,” the title sequence read.

An online game called Wild Burning pits overweight participants against each other, promising its winner 1 million rubles ($17,000) and a car as a reward for losing the most weight. But the rhetoric it uses to communicate with participants goes even further than that of I’m Losing Weight, bordering on rudeness.

“[If you fail the game], you’ll go back to your mom’s pies and your huge ass,” one of the game’s slogans says. “Your dream of new breasts, MiniCooper and money will melt away, just like fat on the hips of your most hated friend.”

Host and founder of Wild Burning, Vasily Smolny, believes honesty is the best tool in motivating people to lose weight. “I bring people down to earth by calling those that are fat, fat,” he told The Moscow Times. “It helps to look at yourself from a different perspective.”

Smolny believes his peculiar tone is what makes the project different from others. In 2016, a similar project was launched by his wife Yuliya, but was much less abrasive in tone. But the couple shut it down because there was too much competition.

“Most trainers and motivation coaches out there are trying to convince people to workout by being nice and sensitive,” Smolny says. “What I offer is completely different and unique — no whining and no tip-toeing.”

Breaking the vicious circle

Smolny says in the two years since it began, Wild Burning has engaged more than 100,000 players in the brutal weight loss competition. Entrance fees vary from 3,000 ($50) to 15,000 rubles ($250).

Why are so many people willing to pay for his “bad cop” approach? It often perfectly fits an overweight person’s view of themselves, suggests psychologist Belyakova: “You think that you’re a fat, weak pig and that you deserve to be treated as such in order to make the change happen.”

“Interestingly enough, when you bounce back from this weight loss — and you inevitably do, once you stop doing this extreme routine — you only blame yourself for failing something that has worked out so well for you. It is a vicious circle of self-hatred.”

The positive body movement that promotes self-acceptance — no matter how fat, old or ugly a person might think they are — is one of the ways out of the never-ending negativity, the psychologist says: “It helps to ease up on themselves, stop hating their bodies and relieving this constant tension in their lives.”

Svolochova says her online community, which has been running for four years and attracts more than 68,000 members, does exactly that.

“We give women the chance to talk — about themselves, about their bodies, about their feelings,” she says. “It’s about offering a safe environment for discussion, understanding and support.”

The next step should be seeing a specialist, Belyakova says, since body image issues are not something that easily goes away. Scandals like Aeroflot’s help, she believes: “At least people are now talking about it, discussing the problem and becoming more aware of it.”

Yevgeniya Magurina continues to work as a flight attendant, but mostly on Russian domestic flights.

She says she has only begun her legal challenge. She may have had her case struck out in her local court, but she plans to appeal the ruling in other Russian courts. She is even prepared to take her discrimination case all the way to the European Court of Human Rights if need be.

“I’m quite happy with my body,” she says. “I’ve never been thin — not everyone is supposed to be a size XS — but I was really insulted by this. It still hurts.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.