When Russian President Vladimir Putin came to Yerevan in November I took part in a protest against the war in Ukraine along with around 20 other Russian migrants to Armenia. We later joined a rally held by a local political party calling for Armenia to end its dependence on Russia, marching with them through the city chanting "Russia is the enemy" and "Putin is a thief and murderer." Despite the arrival of thousands of Russians in the Armenian capital over the past year, the Russian contingent at the protest was tiny, and it was only the far more impressive Armenian turnout that lent the protest any legitimacy at all.

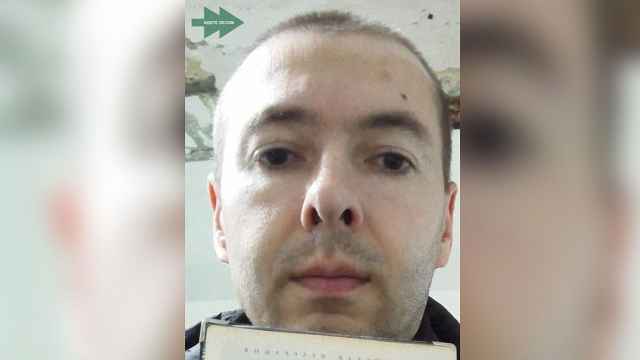

I define myself as a Ukrainian, although I was born in Moscow and have lived there for most of my life. My Ukrainian father brought me up identifying as Ukrainian with my Russian mother's support, even though her relatives disapproved. I attended weekend classes to learn Ukrainian and always spoke the language with my father. Growing up, however, I often heard the opinion that a separate Ukrainian identity did not exist, and that being Ukrainian was somehow a deviation from the norm.

Today, my father’s neighbors in Moscow call him a fascist, because that’s what the television tells them about Ukrainians. I’m afraid they may report him to the police, and can only hope that, at the age of 82, he won’t be put in jail. However, in recent months I’ve seen that the repressive Russian state will stop at literally nothing.

I rang my parents in tears on the morning of Feb. 24, when I heard the news that Russia had launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. “You should leave the country right away," my mother told me. "First they’ll deal with the Ukrainians there, then they’ll go after the Ukrainians here."

That day, friends abroad asked me whether Moscow would see protests against the invasion. I knew that there wouldn’t be, based on past experience. After the annexation of Crimea in 2014, I joined a protest on Manezh Square outside the Kremlin, which was swiftly dispersed. There were few protesters and I realized that these puny efforts wouldn’t change anything.

A friend of mine from Kyiv said she couldn’t understand why people in Russia don’t protest. I was unable to give her an answer because every time I went out to protest and found myself running away from the riot police in fear, I would wonder where everybody else was. The lack of protesters meant it was easy to catch the few dissidents that did show up.

While I knew it wouldn’t stop the Russian missiles, I took part in a protest against the invasion in Moscow on the evening of Feb. 24, as I felt that doing nothing wasn't an option. If the repressive measures used by the state were only just gathering momentum after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, they were by now in full swing, and there was every indication that things would only get worse. Speaking to my friends, I could tell that those who opposed the war were simply too afraid to go out and protest.

The invasion of Ukraine dashed all my hopes for change once and for all. Although democracy in Russia may seem forever doomed to fail, I refused to abandon my humanist beliefs. Nevertheless, I realized that the country was slowly but inevitably plunging into the abyss.

I was waiting for us to hit rock bottom so that when things began to improve I could be part of the movement to create a democratic society in Russia. But the future I imagined did not involve such a brutal war.

Working in cultural activism since 2010, I was fully aware of the fundamental change that occurred in Russia in 2014. Before then, most of the projects I worked on were still funded by the Moscow city government — even when they involved controversial issues such as training independent journalists, supporting political prisoners, or protecting LGBT rights. Since 2014, critically minded citizens found themselves increasingly alienated from civil society and the events I organized began to attract the attention of the FSB.

Nevertheless, I found a way to continue my Kremlin-critical activities by creating a cultural space independent of the state and turning it into a small business to support niche civic initiatives.

Like hundreds of thousands of Russian citizens though, in 2022 I ended up emigrating in protest against the war. In Yerevan, I became friends with other Russian migrants and while I met plenty of people whose motivation for emigration was ideological opposition to the war, there were also those who chose to leave Russia primarily for their own convenience.

One October evening, a Russian friend in Yerevan had a small party at his apartment where all the guests were recent arrivals from Russia. Discussing the war, I told them about an experience I had in Tbilisi meeting some friends from Kyiv. The café where we met was full of Russians who seemed completely oblivious to the war, which made my Ukrainian friends very angry. They asked me why Russians didn’t protest against their government even in the safety of Tbilisi. One said: “I’m angry that Russians can continue to live as if nothing has changed, but Ukrainians do not have that option. The war has affected us all, whether we’ve left the country or not. It’s not fair.”

I asked the other party guests what they thought about this statement. One said that “we” weren’t capable of influencing anything, while another said that Russians didn’t want to protest and preferred to simply live in peace, while a third defended himself by going on the attack, saying he had “donated money to the Ukrainian army.”

The three different answers represent a good cross-section of anti-war Russian society, and show how difficult it is for Russians to unite, even against an aggressive, pointless war started by their own government.

Living in Yerevan, I understand that I can’t regularly protest here against the war, or against Putin. We are migrants to our country’s former colonies. These societies have their own conflicts to worry about, and protesting against Putin would mean appropriating their agenda for our own purposes. In every post-Soviet nation, people have their own attitude to the war in Ukraine, and also toward Russians, regardless of our political views. Many of us emigres find it difficult to accept that we are now “enemies” at home as well as uninvited guests in countries still traumatized by Russian imperialism.

While I have made Yerevan my home, for many Russians who have fled abroad, the Armenian capital is just a transit point on the way to Europe. If I can understand why protesting against the war is a complicated issue in countries like Armenia, it is a different situation for those Russians who have managed to relocate to Europe.

I would like to ask migrants from Russia who live in Europe: Why don't you join anti-war protests there? After all, there is no personal risk — and no risk of appropriating the local political agenda. Ukrainians have posted photos on social networks showing thousands of Iranians in the center of Berlin protesting against the regime in their own country, followed by photos of empty Berlin streets with the comment “This is how Russians protest against the war.”

Recently some of my friends in Berlin organized a protest calling for an end to Russian imperialism. But hardly anyone turned up…

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.