The Oxford dictionary last month named “post-truth” its “word of 2016,” indicating that the Western world is only just beginning to grapple with the practice. In Russia, the merging of truth and convenience, an activity long perfected. registered new lows last month, with the Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky denouncing any expert who dared challenge the veracity of popular Soviet legends concerning World War II

Medinsky put forward his version of history during a speech commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Moscow, a famous battle that saw the Soviets fight off a German invasion in 1941-42. Soviet authorities made huge propagandistic use out of the Red Army’s successful defence of the capital. Medinsky mentioned two of the most heroic stories the tales of a Soviet partisan named Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, and a Spartan-like group of 28 warriors “Panfilov’s 28.

According to Medinsky, the study of these soldiers’ lives belongs to hagiography. They must be treated as “saints,” he said. And anyone who casts doubt on these heroes’ bravery should “burn in hell.”

Zoya the Partisan

Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, executed by the Nazis in the village of Petrishevo outside Moscow, was hanged for setting fire to local houses to slow the German advance. According to a Soviet military newspaper, Kosmodemyanskaya’s last words were “There are 200 million of us, you won’t hang us all!”

In Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya’s case, the myth is most likely backed by real bravery. “Zoya’s biographers did not fabricate anything Ñ on the contrary, they actually withheld details about her bravery,” the historian Boris Sokolov wrote in an recent article published in Russia’s liberal-leaning electronic magazine Republic.ru.

According to archival evidence, Kosmodemyanskaya was a “torch-bearer,” ordered by Stalin to burn down populated settlements behind German lines. Many locals living in these towns were naturally opposed to the destruction of their homes, but Kosmodemyanskaya fulfilled her duty. She endured torture in German captivity before meeting her death.

Panfilov’s 28

Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya’s martyrdom is only part of the Soviet mythmaking around the wartime defence of Moscow. Another far less plausible legend belongs to “Panfilov’s 28,” the 28 soldiers who supposedly fought under the command of General Ivan Panfilov and, so the story goes, defeated an entire German tank division on Moscow’s outskirts in early 1941. All 28 men died defending the city according to the official Soviet version.

Russia’s Culture Ministry invested 30 million rubles ($460,000) into a new film about the men, “Panfilov’s 28,” which recently premiered in cinemas across the country. The movie was co-produced with Kazakhstan’s Culture Ministry, which was happy to promote the fact that a large part of the men who fought under Panfilov were Kazakhs. The rest of the film’s budget was reportedly financed by small donations sent in by “ordinary people” eager to see the story come to the big screen.

The legend of the “Panfilovtsy” first appeared in November 1941 as a propaganda article in the Red Star, a Soviet military newspaper. Like accounts of Kosmodemyanskaya’s dying cry, reports about Panfilov’s 28 soldiers gave the Soviet Union another immortal quote, allegedly pronounced by commander Vasily Krochkov: “Russia is vast, but there is no going back! Moscow is behind us!”

After the war, every Soviet school child was taught the story of Panfilov’s 28, and Klochkov’s famous words were printed in Soviet textbooks. The legend became part of the Soviet Union’s national canon.

As early as 1948, however, a secret memo emerged showing that the story had been fabricated. When the Soviet Union collapsed and state archives opened in the 1990s, researchers confirmed this. In 2015, the legend became politically contentious again, after Sergei Mironenko, the long-time director of the Russian State Archives, denounced the story as a myth and published documents proving that Soviet reports about Panfilov’s 28 are phony. Not long afterwards, Medinsky publicly criticized Mironenko, who was soon demoted.

In reality, Panfilov’s division was made up of roughly 10,000 men, most of whom were ethnically Kazakh and Kyrgyz. “They really did fight heroically outside Moscow, and they did so very effectively,” says historian Nikita Sokolov. Sokolov calls the rebirth of the myth “immoral” because it undermines the real achievements of the entire division.

None of this has put off the Russian Culture Ministry. “Even it if was all made up and Panfilov never existed, it’s a sacred legend that people should not touch. Those who do are scum,” Medinsky said in October, after attending a private screening of the new blockbuster film for the presidents of Russia and Kazakhstan.

State on Show

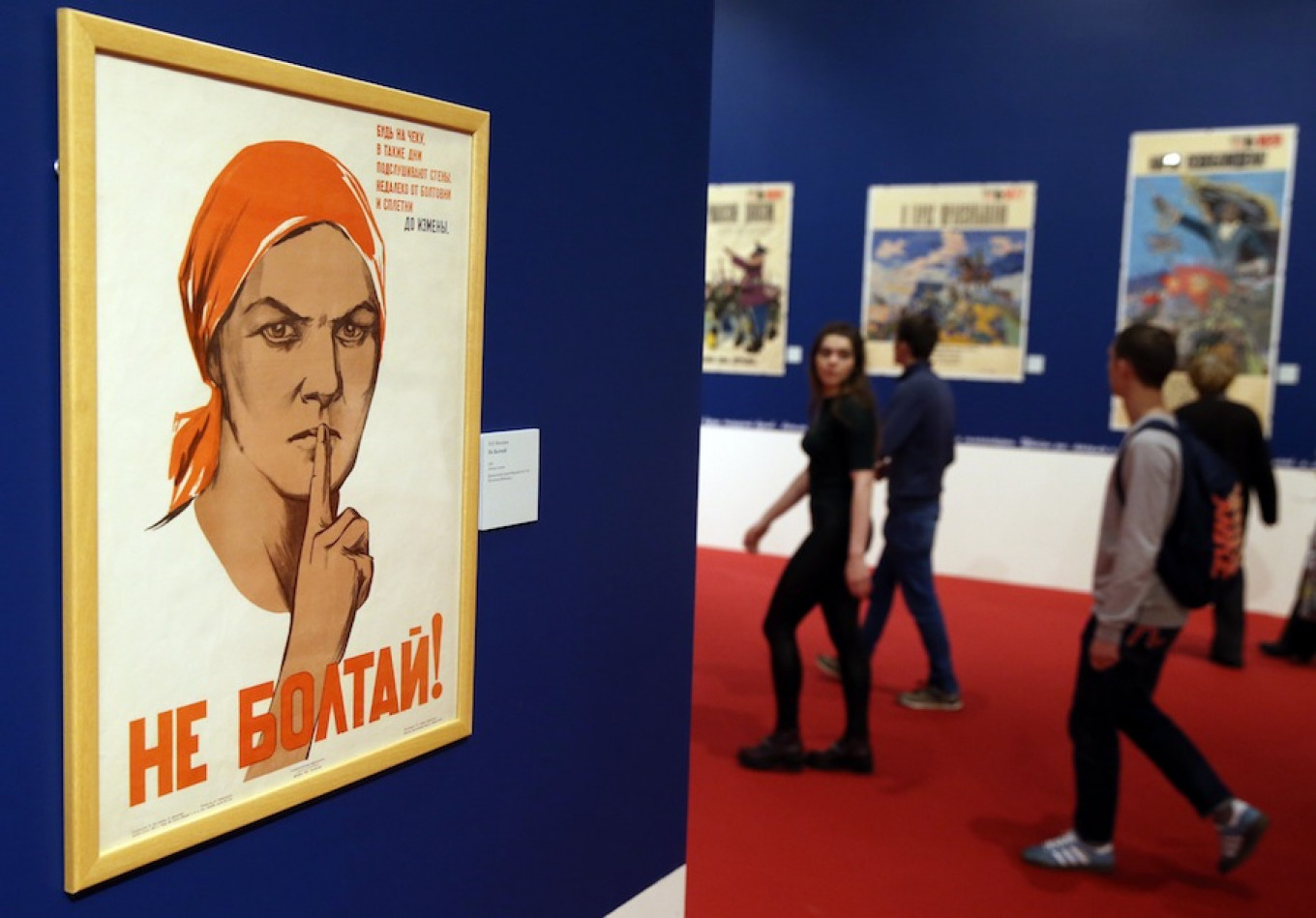

The new film was not the only commemoration of the Battle of Moscow. Ahead of its premiere, a new exhibition titled “War and Myths” opened at Manege Square outside the Kremlin. This, too, was partly the work of Russia’s Culture Ministry, as well as the Russian Historical Society, which Medinsky chairs.

On Nov. 16, when the exhibition opened, Medinsky was on hand to deliver a speech, wherein he called the falsification of history an “information virus” with the potential to “dismember Russia.”

“War and Myths” begins with the story of Panfilov’s 28, and from there the public is treated to a retelling of World War II’s main events, as recorded officially by the Russian state. There are young volunteers walking the floors, dressed in Red Army uniforms, welcoming visitors. One of Medinsky’s articles is on show reprinted in huge script, and framed on a wall. There are interactive displays dedicated to debunking “myths” supposedly invented by Western governments and pro-Western Russians. Visitors are told how “falsifiers of history” are out to build “national identities on anti-Russian grounds,” and propagate “anti-Russian stereotypes” across Europe. Some groups “also hope to challenge” Russia’s status as the Soviet Union’s legal successor at the United Nations.

The exhibition goes some way to rehabilitating the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Stalin was “forced” to create a “tactical alliance” with Germany, the exhibition claims and only after Great Britain and France refused to join his anti-Hitler coalition. The Soviet invasions and occupations of Eastern Europe after the war, moreover, are portrayed as the natural, entirely peaceful spread of communist ideas.

One of the young volunteers, 26-year-old Alexei Nosov, says he sees no contradiction. “I’m sure the Russian army would do the same today if it had to,” he says ambiguously.

Look up and there is a banner of Stalin hanging from the ceiling, depicted making a famous toast to the Soviet people in May 1945, after the end of the war. Look to the ground and you will find names of historians and journalists who have challenged the official “heroic” narrative.

“We made sure to put their names on the floor, so people would wipe their feet on them,” says Nosov.

One of those names visitors are invited to step on is that of Leonid Gozman, a liberal politician who angered Russian history warriors back in 2013 when he said the only thing differentiating Hitler’s SS from Stalin’s Smersh was “a nice uniform.”

Confirming to The Moscow Times he was unaware of the unusual exhibition feature, Gozman’s initially reaction was laughter. “But more seriously,” he says, “it is frightening that all this is happening with the backing of the state.”

Was he personally fearful?

“I am not afraid for myself: I am afraid for my country.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.