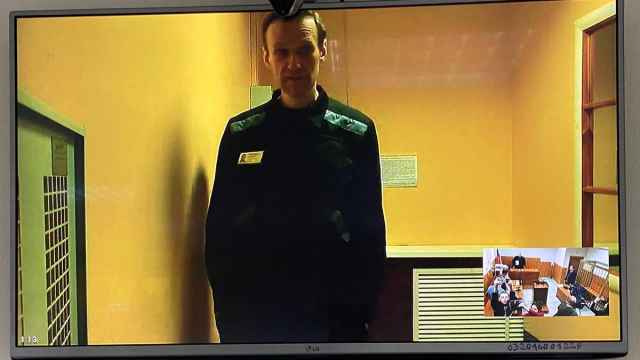

Russian officials said Sunday that Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny is in a prison colony in Vladimir region, three hours outside Moscow, where he will spend the next two and a half years.

Four former inmates of penal colony IK-2 — which Russian state media have identified as the institution where the opposition leader will do his time — told The Moscow Times that it is one of Russia’s toughest prisons.

“This is, by any measure, an extremely strict prison. They try to control your every step, your every thought,” said Konstantin Kotov, who spent two years in IK-2 after being arrested during Moscow’s summer 2019 election protests and convicted under a controversial law criminalizing "repeated" participation in unauthorized rallies.

Kotov explained that Russia has four types of penal colonies, each with a different regime depending on the severity of inmates’ crimes.

Navalny’s prison has a so-called “ordinary regime,” with prisoners housed in large barracks with up to 150 beds in each. However, according to Kotov, conditions in IK-2 are more in line with those seen in “strict regime” penal colonies.

“Inmates who have spent time in different prisons across Russia told me this was the toughest one they have been in. It definitely felt like a high-security prison for hard criminals,” he said.

The decision to transfer Navalny to IK-2 was met with concern by human rights workers who monitor the rights of prisoners in jails across Russia.

Pyotr Kuryanov, a lawyer at the Defence of Prisoners' Rights Foundation NGO said he was shocked when he first heard the news that Navalny was to be transferred to the Vladimir prison.

“It’s completely lawless there. They will break you. Bad things have been going on there for a long time, some of it exposed by Vladimir Pereverzin 10 years ago,” he said, referring to a former manager at the Yukos oil company who, like his boss Mikhail Khodorkovsky, was prosecuted on corruption charges and spent seven years behind bars.

Pereverzin’s last two years in jail, from 2010 to 2012 were spent in IK-2, which he described in a memoir.

In a phone conversation from Berlin, where he now lives, he said Navalny was in for a “tough time.”

“The conditions were certainly grim there. The prison is next to a swamp, it is cold and wet with bad food. It was a violent place back then.”

“Like torture”

Most of the prisoners in IK-2 are there on drug and theft charges, said lawyer Kuryanov. However, he added that the colony occasionally hosts high-profile political prisoners, including Pereverzin, Kotov and the nationalist activist Dmitry Demushkin who spent two years in IK-2 for inciting hatred.

In an exchange of text messages with The Moscow Times, Demushkim described his time in IK-2 as being “like torture.”

He said he spent his first eight months in the prison in its notorious second sector, known among prisoners as SUKA (Russian for bitch), where conditions were particularly harsh.

“I was forbidden to talk to other inmates, they were forbidden to look at me, my hands were always behind my back when I was out of my cell. It was forbidden to attend the local prison church, to do any sporting activities.”

Both Pereverzin and Kotov said they did not experience severe physical violence from guards, which they believed was due to their public profile, a factor that should keep Navalny from being physically assaulted.

“The guards will not want a national scandal,” said Pereverzin.

All three former prisoners, however, said they had seen and heard of other inmates being beaten by guards and other prisoners.

Russian prisons have been plagued by torture scandals for years. Just last week, the Russian independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta published video footage claiming to show the brutal torture of Russian inmates — one of whom died shortly after the footage was filmed — in Yarosvlav, a region bordering Vladimir.

Alexei, a 57-year-old former inmate who asked that his last name be withheld, spent two years in IK-2 for burglary until his release last summer. He told The Moscow Times that he was repeatedly beaten by both guards and prisoners during his time in jail.

”There is a whole system in place that permits daily violence and humiliation,” Alexei recalled, adding that he hoped the newfound focus on the prison would bring some of the alleged abuses to light.

“Maybe something good will come out of this,” he said.

The administration of IK-2 did not respond to The Moscow Times' requests for comment.

Psychological isolation

On his arrival, Navalny will spend two weeks in quarantine, which is located in the notorious second sector. After that, much will depend on the type of barracks he is sent to.

Kotov believes the authorities chose to put Navalny in IK-2 because it is effective at “psychologically isolating” political prisoners.

He pointed to the fact that the colony does not allow emails, and said prison guards would take “weeks and sometimes months” to read through and process each letter he received or sent by post. During his time there, Kotov said he would never get more than an hour a day to reply to the many letters of support he said he received.

In jail, Navalny is also likely to find himself isolated from the other prisoners.

“They forbid other inmates to talk to you. They want to make you feel alone,” said Kotov.

“All of this is meant to wear you down psychologically,” he added.

Pereverzin echoed Kotov, saying that during his time there a decade ago, other prisoners were instructed to “avoid him like the plague.”

Nationalist Demushkin said guards also went to great lengths to restrict his flow of information while he was in IK-2.

“We were not allowed to talk about politics or religion,” he said, adding that convicts were only permitted to watch Russia’s state-controlled Channel 1 television station.

Looking back at his time in jail, Kotov now thinks he might have been a “test case” for how to isolate a prominent political prisoner like Navalny.

“But I am sure Alexei is strong enough to handle whatever comes his way” he said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.