Suddenly, spies are in the news again. Former U.S. Marine Paul Whelan has been convicted of receiving classified information. A Russian scientist has been accused of passing secrets to China. A Russian diplomat in Prague was, for a while, wrongly identified as an assassin. Taken together, these cases tell us something about Russia’s place in the world and, more to the point, its mindset.

America: let’s make a deal

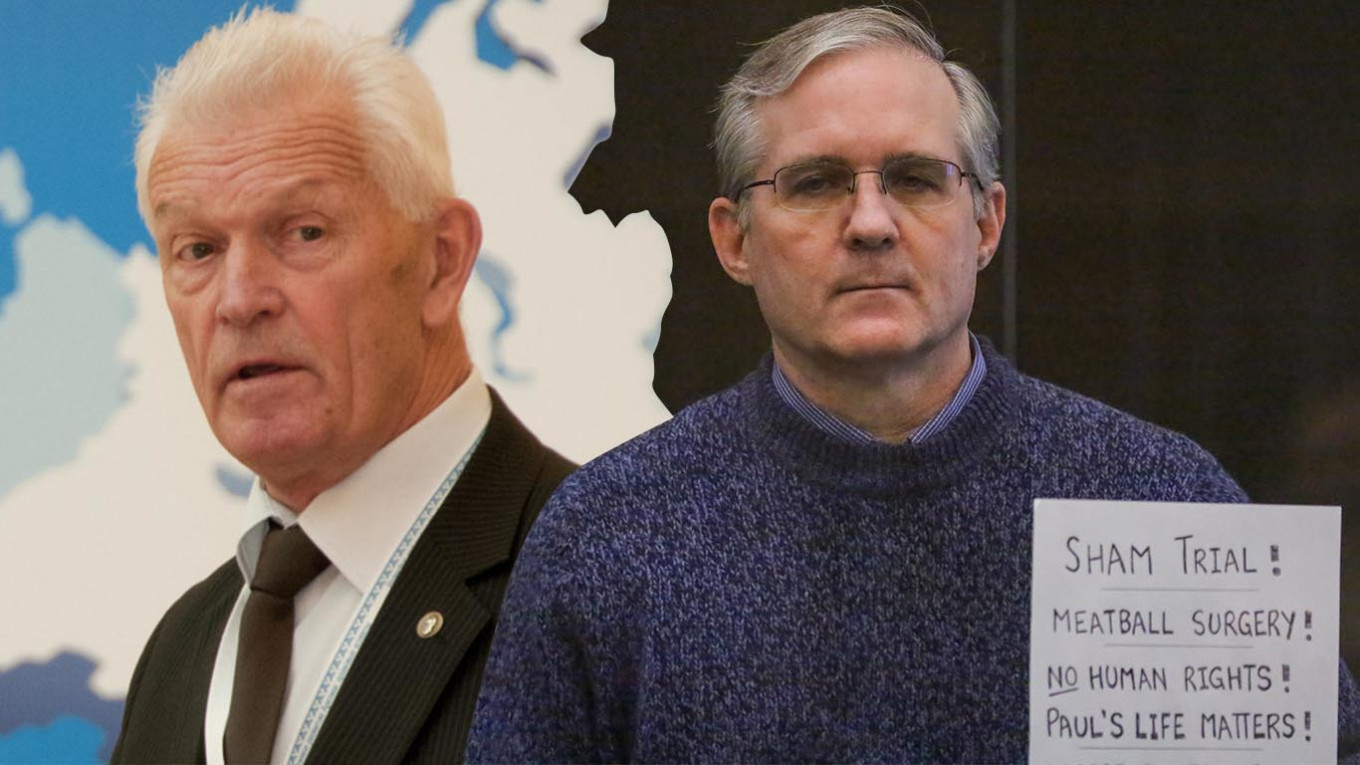

The case against Whelan looks at best a flimsy one. The accusation is that, while ostensibly in Moscow for a wedding, he was in receipt of a USB drive with the details of the staff of a security agency. For good measure, the prosecution claimed he is “at least a colonel” in the U.S. Defence Intelligence Agency, even while holding down a job as director of global security for automotive parts manufacturer BorgWarner.

Although the notion that he would be both in the DIA and working at BorgWarner is implausible – it probably simply reflects the Russians’ own habit of placing so-called “active reserve” officers in the civilian sector – it is not wholly implausible that someone like Whelan might be used as a courier or cut-out. Usually, though, Moscow is only too willing to parade the evidence it has; its absence in this instance does lend plausibility to the belief Whelan was framed.

But why? It may simply be that Whelan was wrongly identified as an agent and the authorities preferred to go ahead with, as he put it, a “sham trial” rather than admit a mistake.

More likely, he was suspicious enough to them — an ex-marine actively seeking out Russian officers on social media and travelling often to Russia — that he seemed a good candidate to seize as a potential swap for one of several Russians currently being detained in America.

We will have to see if this happens. There is the arms dealer and likely GRU (military intelligence) asset Viktor Bout, although he is probably regarded as far too valuable for such a deal. There is the drug-running pilot Konstantin Yaroshenko, maybe even the hacker Alexei Burkov, whom Moscow had previously tried to swap out of Israel.

Either way, this underlines Moscow’s essentially transactional approach to international politics — and its assumption that Donald Trump’s Washington is just the same. And in many ways it is, but Trump does not shape U.S. foreign policy alone, and even if the U.S. ends up making a deal, the legacy of anger and suspicion that such cases where people are treated simply as bargaining chips generate will outlive his administration.

China: signalling desperation

The Chinese case, though, is in some ways more telling. Valery Mitko, the 78-year-old president of the Arctic Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, has been accused of passing military secrets to Beijing.

His case is very similar to that of 75-year-old Vladimir Lapygin, sentenced to 7 years in prison in 2016 for giving China military-technical secrets, and recently granted early release. In both cases, the men claim they were simply sharing open knowledge.

There is, of course, no doubt that China spies on Russia (and vice versa). Mutually Assured Snooping is the order of the day in the modern world. As well as the usual political and military intelligence it is ruthlessly seeking to plunder the remaining crown jewels of Russian science and technology.

In the main, though, Moscow handles its spy war with China very differently from that with the West. When the latter’s spies are caught, this becomes a media circus. Chinese agents, though, are often quietly expelled after a word with the ambassador, their local assets arrested on different charges or discretely handled some other way.

In other words, there is a degree of conscious theatricality to how espionage cases are handled. They become fodder for the intertwined narratives that the West is an aggressive threat and China a trusty partner.

This has, however, its own problems. It certainly does nothing to deter Beijing’s increasingly active espionage operations, which parallel the sustained upsurge experienced in the West. It is also exasperating elements within the security apparatus, who feel they are being held back from addressing the threat.

However, this year has seen China suddenly become much more assertive, even aggressive, from the push-back over claims of a coronavirus cover-up to tightening its grip on Hong Kong. This has worried Moscow, for whom its much-touted partnership with Beijing was always more of a “frenemyship” and an ever-more asymmetric one, at that.

Its worry is precisely that it is forced into becoming little more than a Chinese vassal, when it really wants to use Beijing to recalibrate its own relationship with the West

The publicity given this case — arguably out of proportion with what a septuagenarian academician may have said in 2017 — could thus be taken as an act of signalling, hoping to draw a line in, if not the sand, at least the ice. That said, if other countries’ experiences are anything to go by, Beijing is not so easily deterred.

Russia: woes of the spook superpower

Itself ruled by a former spy, Russia has for some time leaned on its intelligence services both as active instruments of its foreign policy but also part of its whole “dark power,” its capacity to intimidate where it cannot win friends.

This has not been wholly ineffective, but the rather bizarre Prague case also illustrates some of its risks. What appears to have been an internal row between two Russian diplomats led to an international incident in which they and then, in the usual banal tit-for-tat, two Czechs have been rendered persona non grata.

The allegations of a Russian multiple-assassination plot were surreal, but taken seriously, not least because of the murderous reputation of Moscow’s agents, given cases from Berlin and Istanbul to Salisbury and Qatar.

Just as Moscow’s treatment of foreign — real and imagined — spies is indicative of how it views its interactions with other countries, so too its reliance and indulgence for its own intelligence agencies colors its relations with the outside world. It may be fun to feel like a spook superpower, but it may well prove counter-productive.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.