Russia halted oil flows along the Druzhba pipeline to Eastern Europe and Germany last week because of contaminated crude, a move that helped lift global oil prices to a six-month high and left refiners in Europe scrambling to find supplies.

Below are details about the problem and action being taken:

What happened?

At least 5 million tons of oil, or about 36.7 million barrels, have been contaminated by organic chloride, the chemical compound used to boost oil extraction by cleaning wells and accelerating the flow of crude.

The compound must be removed before oil is sent to customers because it can destroy refining equipment and, at high temperatures, generates poisonous gas chlorine.

Russian pipeline monopoly Transneft said the contamination happened in the Volga region of Samara and blamed unnamed "fraudsters." President Vladimir Putin said Transneft lacked a proper mechanism to prevent contamination.

What is the impact?

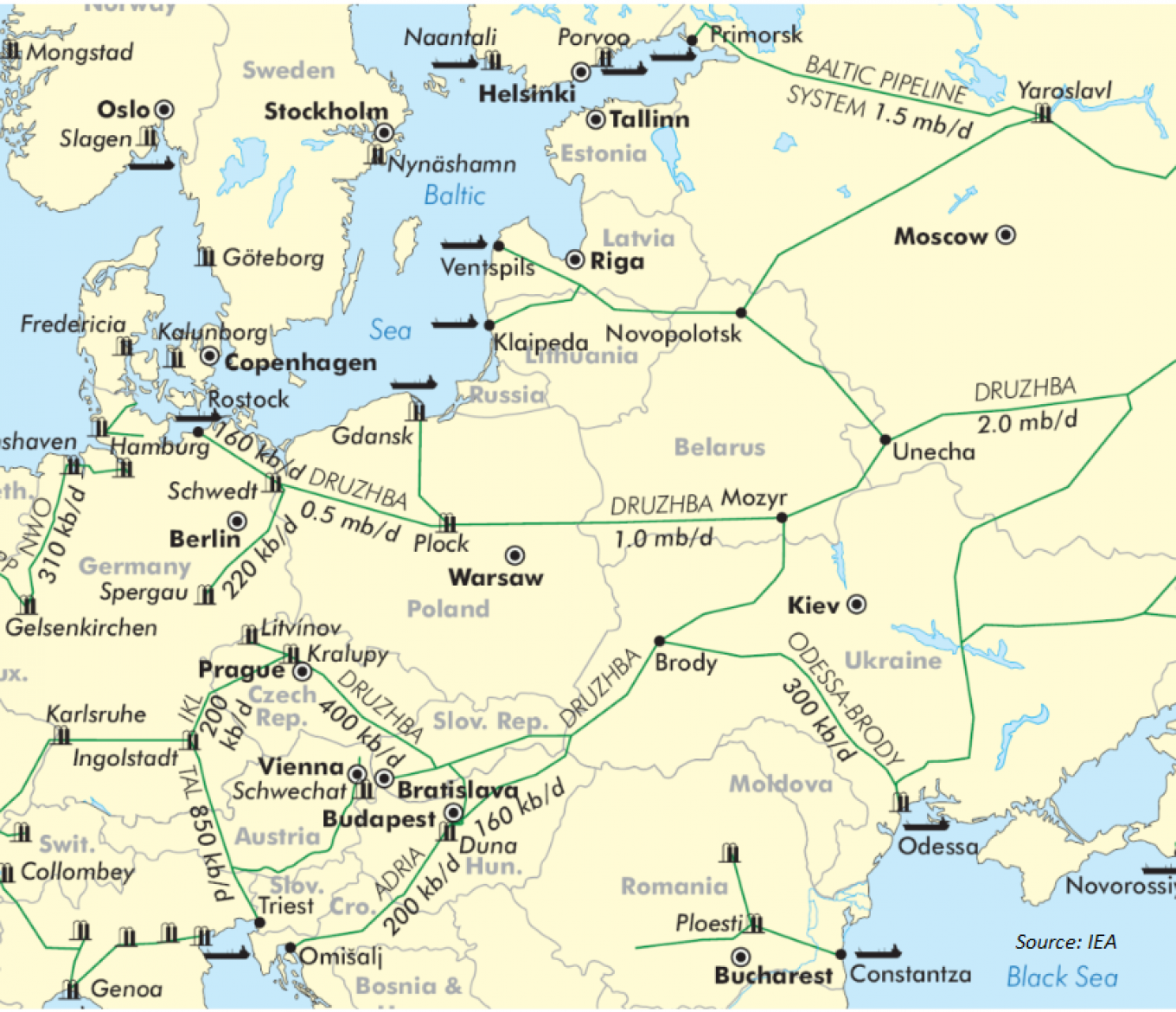

The Druzhba pipeline, which can pump 1 million barrels per day or the equivalent of 1 percent of global oil demand, was build in Soviet times and serves refiners in Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Ukraine and Belarus.

All the importing nations stopped taking Russian oil via the pipeline since April 25-26.

Belarus, where the pipeline splits into northern and southern spurs, began receiving clean oil this week but most pipelines in the country and further along the network remain contaminated.

Belarus said it might take months to resume normal operations.

What have refiners done?

In Germany, the main refiners served by Druzhba are Rosneft's Schwedt, Royal Dutch Shell, Eni and Total's Leuna. Industry sources say the plants are seeking alternative supplies and have yet to cut refining runs.

Hungary said it would release 400,000 tons of oil from its emergency reserves to supply a refinery owned by MOL.

Czech refiner Unipetrol asked the government to loan oil from state reserves.

Poland's Lotos said it would tap strategic reserves, while its bigger rival PKN Orlen has said it had no plans to do so.

Were other oil outlets affected?

Besides the Druzhba pipeline, oil sent to one of Russia's top Baltic Sea ports Ust-Luga was also contaminated.

At least 10 tankers with a combined 1 million tons of oil, normally worth more than $500 million at current prices, have already sailed from Ust-Luga since the problem arose.

Trading house Vitol refused to take a cargo from Ust-Luga last week, forcing the port to shut for 24 hours.

Ust-Luga reopened for crude loading on April 26 but, as of April 29, levels of chloride were still high.

Transneft allows no more than 10 parts per million (ppm) of organic chlorides, while levels in the Druzhba line and Ust-Luga have fluctuated between 80 to 330 ppm.

Russian oil firm Surgutneftegaz repeatedly failed to award two prompt Urals May cargoes from Ust-Luga at a tender this week, even after offering discounts for chloride contamination.

How can this be fixed?

Buyers who have received contaminated oil now need to store it somewhere and dilute it with cleaner crude to lower the chloride levels, an operation that could cost millions of dollars for each large crude tanker, oil trading sources say.

Oil at Ust-Luga port could gradually be loaded onto ships mixed with better quality crude.

But cleaning out the Druzhba pipeline is not so simple.

Germany and Poland lack sufficient storage tanks to keep the oil until it can be diluted. That means they would need to reverse the flow of the pipeline and pump tainted crude back to Russia or to Poland's Gdansk port, where it can be evacuated.

Transneft has said contaminated oil from Belarus could be transported by railway to Russia's Black Sea port of Novorossiisk, where it would be diluted.

This would take several months because the railway cannot take more than 300,000 tons per month, traders say.

Update: Clean oil has reached Belarus via the Druzhba pipeline from Russia, Belarus state oil company Belneftekhim said on Thursday. No other details were revealed.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.