U.S. gun enthusiasts live in constant fear of the federal government confiscating their weapons. For Russian gun owners, such a fear may be about to become a reality. On April 14, President Vladimir Putin, announced the formation of a new National Guard, and declared one of its key fuctions would be to control firearms.

"We are creating the National Guard to limit the circulation of weapons in the country," he told the Russian people during his annual "direct line" national call-in show. What wasn't clear was whether Putin was referring to guns legally owned by law-abiding Russians or to the stockpiles of illegal weapons flowing throughout Russia, fueled by the numerous wars on its borders.

Russia has a short history of private gun ownership — it was rare during the Soviet era — but the country's stillborn civil society has started to push for greater access to firearms. Despite the government's apparent willingness to make concessions, statistics still show that many gun-owning Russians prefer to skirt the bureaucracy and keep their unregistered guns off the radar — for one reason or another.

Up until now, the Kremlin had shown little sign of obvious concern. Yet, as millions of unchecked firearms flow through a nation reeling from economic crisis, some of their calculations are changing.

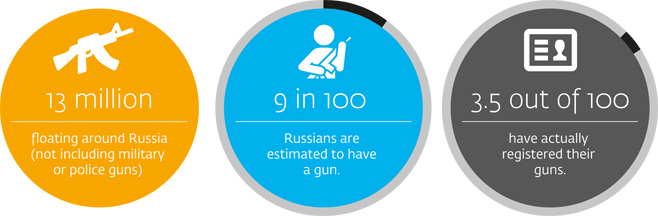

According to the most recent international surveys, roughly 9 percent of Russians own a firearm. Of the estimated 13 million guns in civilian hands, only around 60 percent are legally registered.

If Putin indeed intends to use the National Guard to track down these weapons, it wouldn't be without precedent. "We have already seen a progressive tightening of the rules for citizens and private security firms alike," says Mark Galeotti, an expert in Russian security services and criminal affairs. "But even after attempts to clean up the registration of firearms, there are many illegal guns in circulation in Russia."

There are, however, reasons to doubt the National Guard has really been set up to search for guns. They have no investigative capacity and the only way to fulfill such a task would be to conduct house-to-house searches, an invasive and labor intensive process.

The types of illegal weapon used for the most serious crimes in Russia — contract killings, terrorism and similar types of activity — are often not unregistered shotguns, but military-issue firearms that Russian citizens don't have access to. "In other words," says Galeotti, "they are stolen from official stocks, essentially through corruption."

Internet Shopping

You don't need to be a corrupt policeman or military officer to procure weapons in Russia. There are many other options, ranging from the physical black markets peppered around Moscow to more modern, darker sources. These are the markets based in far-flung corners of the Internet, absent from the usual indexing services like Google or Yandex.

Those with the requisite technical savvy can get their hands on almost anything they want, provided they know where to look. One source, on condition of strict anonymity, directed The Moscow Times to one such online black market.

The process of getting there requires navigating to the labyrinthine depths of the dark web, and inputting a complicated chain of letters and numbers. Once there, you can access anything from drugs and weapons to information on building bombs. All transactions are facilitated anonymously via the Bitcoin electronic crypto-currency.

Such markets provide troves of information for would-be gun criminals. For example, one forum explains to first time buyers that a gun bought in central Russia costs up to $3,000, while weapons in Crimea are closer to $2,000.

If Interior Ministry statistics are any guide, Russians are more likely than ever to attempt to procure illegal weapons. The ministry recorded 27,000 violations over the course of 2015, an all-time high. The trend coincided with a rising crime rate of 8.6 percent, according to Gazeta.ru.

Some illegal guns are antiques, others are hunting rifles, but they have not been registered. Black-market guns have proliferated while gun ownership laws restrict the number and type of gun legally available.

At a glance

'Evening the Odds'

Maria Butina is the founder of Russia's first gun rights advocacy group. A tall, red-headed Siberian native in her late 20s, Butina called the group "The Right to Bear Arms," and it now boasts 10,000 members.

While the government looks at ways of increasing public safety by reducing gun onwnership, Butina's movement argues the opposite is the only answer. When crime increases, they say, ordinary people should be armed.

"We know a simple truth," says Butina. "More legal guns equal less crime. If a country bans guns, only criminals have access to them. We believe in evening the odds for the average Russian."

Many types of weapons, such as pistols and revolvers, remain off-limits to the Russian public. When they were developed, gun ownership laws were designed to enable Russians to hunt.

The bureaucratic procedure to legally procure a gun is complicated.

Any Russian choosing to legally own a gun is initially limited to a single shotgun, which is subjet to a permit. That permit is only granted after a citizen undergoes background checks, investigations into their criminal history, neighborhood circumstances, mental health and invasive home inspections. They also submit to future snap inspections by police. Five years after receiving a shotgun permit, they can then buy a hunting rifle.

Butina's group can claim moderate success in influencing government policy. Two years ago, they collected 100,000 signatures petitioning the government to pass the so-called castle doctrine law, legislation that grants citizens the right to defend themselves and their property from danger using lethal force.

The group has also provided legal defense for Russians like Yevgeny Kostirin, who killed an armed intruder, and Alexei Urazov, who severely injured an attacker in his apartment stairwell with a pneumatic pistol, a weapon legal in Russia. The gun advocacy group can boast legal victories in both cases, but their final triumph is yet to be secured. While the State Duma passed the castle doctrine bill in 2014, it is still to be signed into law by the president.

Putin's comments on the National Guard suggest that the Kremlin isn't as keen on the idea of armed citizens as Butina's group would hope. But she is now backed by the Russian gun industry, which — if the U.S. model is any indication — can be a powerful ally.

Russia's gun industry, which is actively targeting civilian gun markets abroad, is also pushing for increased access to firearms within Russia. Ruslan Pukhov, the head of Russia's Association of Gunsmiths, is confident of progress. According to Pukhov, the clear trend for gun rights in Russia is toward liberalization. "It's two steps forward and one step back," he says.

Broader support among the Russian public is not, however, forthcoming. Though Butina claims that up to 44 percent of Russians now see the value of bearing arms, data from the independent pollster Levada Center indicates the opposite. A 2013 poll showed that 80 percent of Russians remain wary of liberalizing gun rights — these figures have remained constant since the poll was first run in 1991.

Butina is undeterred, saying the public "lacks proper understanding" of the role of guns in modern society.

"Some people think guns have a will of their own; that guns kill people, rather than bad people killing people," she says. "Removing guns from criminals is all well and good, but the best 'National Guard' would be ordinary people with legal guns ready to defend the Motherland."

Contact the author at m.bodner@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter at @mattb0401.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.