A Moscow court sentenced veteran human rights campaigner Oleg Orlov to two-and-a-half years in prison on Tuesday for speaking against the war in Ukraine and “discrediting” the Russian military.

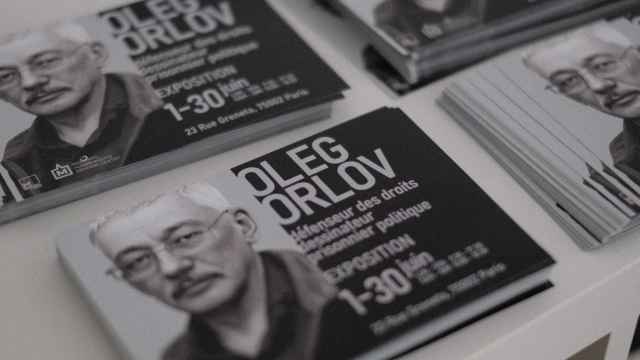

Orlov, the co-chair of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Memorial human rights group, is one of the few prominent anti-war figures who have stayed in Russia since the invasion. His sentencing comes after prosecutors sought a retrial of his previous verdict and requested he be jailed.

Ahead of his sentencing on Tuesday, Orlov told The Moscow Times that he viewed the prosecutors’ request to jail him as “a demand from the top,” but said he still has hopes for change in Russia.

“I believe in a better future [for the country]. There's a true future ahead of us, and there is nothing but the past behind [the regime],” Orlov said in an interview, referring to the Russian authorities.

Orlov, 70, was fined 150,000 rubles ($1,500) in October after a Russian court found him guilty of “discrediting” the Russian Armed Forces.

The charges under Russia’s wartime censorship laws carry a punishment of up to five years in prison. At that time, prosecutors issued the fine due to mitigating circumstances including Orlov’s age and testimonies by his supporters.

Russian authorities accuse Orlov of “discrediting” the Armed Forces based on an article he wrote in November 2022 titled: "They Wanted Fascism. They Got It."

In his article, Orlov stated that the war against Ukraine is “a severe blow to Russia’s future” and that the Kremlin seeks to use the invasion as a tool to achieve its political goals.

Prosecutors this time claim that Orlov had “a motive of enmity and hatred towards military personnel” which they consider aggravating circumstances.

“I do not plead guilty, and the accusation is not clear to me,” Orlov said during a hearing this month.

In his interview on Monday, Orlov told The Moscow Times that he “understood the threats” he faced for opposing the war in modern Russia.

“This trial which lasted for a year is not easy for me and I don’t know if I would have published the article if I had known the consequences. But it seems to me that I would,” he said.

Despite the intensified pressure on independent voices and the mass exodus of activists, politicians and journalists since the start of the war, Orlov chose to remain in Russia.

“I didn't want to run away from prosecution,” he told The Moscow Times.

“In addition, the trial was a chance to convey my ideas and beliefs to the public — at a time when there is no opportunity to speak freely in Russia, I used the court as a tribune,” he said.

In his last word in court on Monday, Orlov once again denied his guilt.

“I haven't committed a crime,” Orlov told the judges.

“I am being tried for a newspaper article in which I called the political regime established in Russia totalitarian and fascist. The article was written more than a year ago. And then some of my friends thought that I was exaggerating things too much,” he said.

“But now it’s absolutely clear that I wasn’t exaggerating at all. The state in our country again controls not only social, political, and economic life, but also claims complete control over culture, scientific thought, and invades private life.”

“It becomes all-encompassing. And we see it.”

Orlov, who was recently added to Russia’s “foreign agents” list, has been a vocal critic of the invasion since its start.

He was detained in 2022 for a one-man picket on Red Square — where he held up a sign reading: “Our unwillingness to know the truth and our silence makes us accomplices to this crime” — and later for another protest against the war.

The United Nations and Amnesty International have urged Russia to drop the charges against Orlov, calling them politically motivated.

“This case is an example of the intensified repression of human rights defenders in Russia, where the judiciary has given up its independence under political pressure,” Mariana Katzarova, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Russia, said this week.

“Orlov’s trial is not just an attack on the individual, but an orchestrated attempt to silence the voices of human rights defenders in Russia and any criticism of the war on Ukraine.”

A human rights defender since 1988, Orlov is a member of the prominent and respected human rights group Memorial, which jointly received the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize alongside Ukraine's Center for Civil Liberties and jailed Belarusian human rights activist Ales Bialiatski.

Orlov was part of a group that swapped themselves for civilian hostages taken by Chechen fighters in 1995 and were eventually released.

In 2004, Orlov became a member of the Russian presidential human rights council.

Orlov appealed the first court verdict last year, calling it "illegal" and "unjust."

At Monday’s court hearing, Orlov also urged Russians not to lose hope for their country.

“I will add on my own behalf: do not give up and do not lose optimism,” he said.

“After all, the truth is on our side.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.