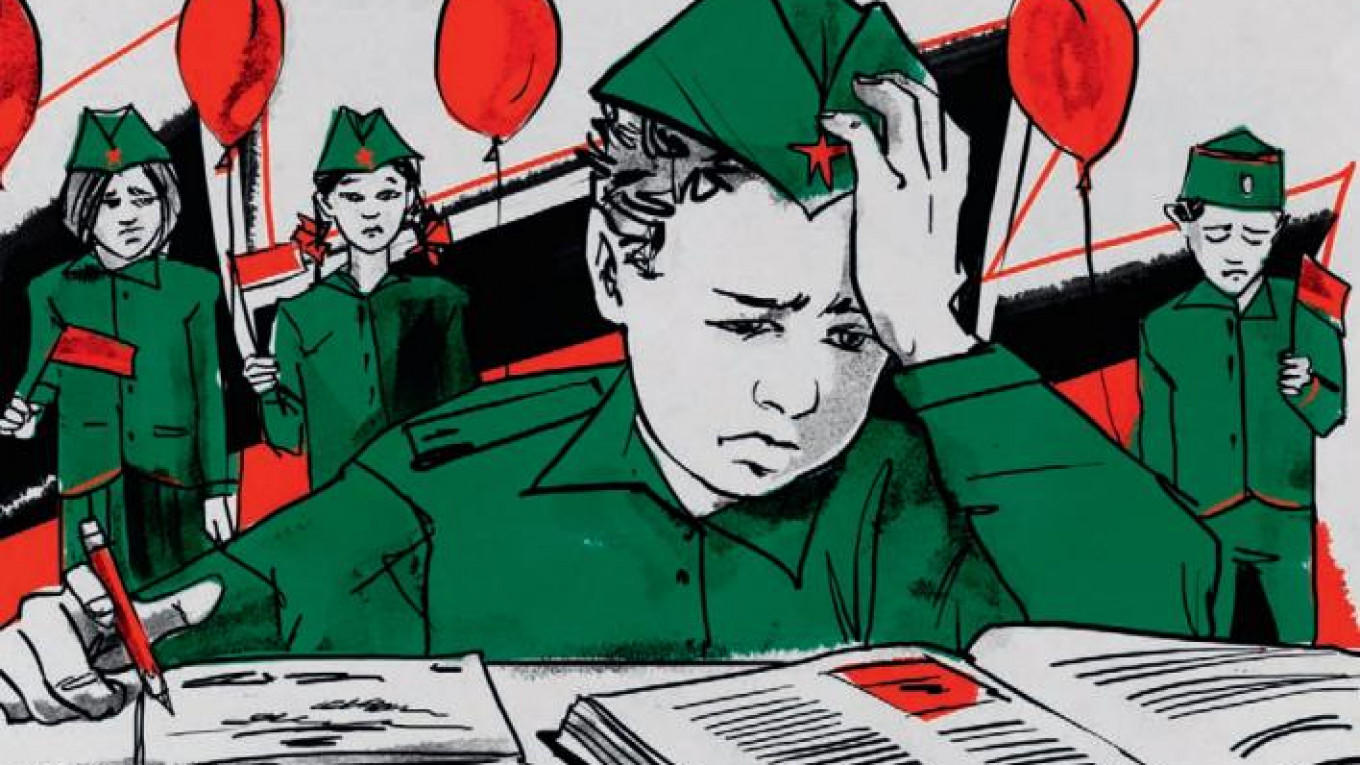

From Kaliningrad to Vladivostok, Russian schoolchildren are preparing for the most important holiday of the year: Victory Day. Commemorated with a grand military parade on Moscow’s Red Square every May 9, the Soviet Union’s defeat of Nazi Germany has long been used by authorities to rally support for the state. And it starts in school.

Russian students play a central role in the patriotic celebrations: popular Victory Day merchandise for children ranges from mini Red Army uniforms to toy guns. They also lead the Immortal Regiment, a march where participants carry portraits of relatives who fought and died in World War II. Entire classrooms are taken to the event.

Amid the euphoria surrounding the event, however, Russia’s history teachers are finding themselves under pressure to conform to the Kremlin’s interpretation of the war.

“Everything that is forced is bad,” says Alexander Abalov, a history teacher at a prominent Moscow school. Abalov is not the only history teacher worried about the state’s interference in his job.

Teaching history has never been easy in Russia, where archives are closed and transparent discussions about the country’s Soviet past are met with hostility. Even then, teaching World War II is more difficult: with every year that Putin is in power, Russia fails to confront its role in the war head on.

In August 2016—on the eve of the new school year—a new Education Minister, Olga Vasilyeva, took office. Vasilyeva is perceived as a supporter of the conservative Orthodox agenda. She has also defended Soviet policies and made controversial statements about Stalin.

While control over the classroom is supposed to be in the teacher’s hands, a new set of history textbooks introduced this year presents a view of the Soviet role in the war uncannily close to Vasilyeva’s—and the Kremlin’s.

In September 2016, three history textbooks were sanctioned by the Ministry of Education, all of which gloss over Stalin’s crimes and his initial alliance with Nazi Germany. “My main issue with the textbooks is that they do not reveal the whole truth,” says historian and teacher Leonid Katsva.

What is still unclear is who decides which book should be used in the classroom. “Is it the teacher, the school director or the city? I asked this question to the Moscow city government many times and received no answer,” says Abalov.

Most schools across the country have sided with one of them, published by Prosveshenie, whose retelling of the war focuses almost exclusively on the heroic aspects of the Soviet war effort.

The pact was defensive!

For Russians, World War II began—not in 1939 as it did for the rest of the world—but in 1941. What happened before, and the Soviet Union’s role in it, has stirred emotions and denial in Russia. The most controversial moment, which the Kremlin traditionally does not emphasize, is the Molotov–Ribbentrop “non-aggression” pact between the USSR and Nazi Germany.

Putin has made contradictory statements about the pact. He struck a conciliatory tone in 2009 when he spoke in Gdansk in Poland, saying the Russian parliament had condemned the pact. Six years later, in a meeting with Germany’s Angela Merkel, Putin said the pact “made sense for ensuring the security of the Soviet Union.”

Other Russian officials have also defended the Soviet alliance with the Nazis. Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky, known for his pseudo-historical novels, has said that the pact “deserves a monument.”

But publicly questioning Russia’s role in World War II in 1939-40 is controversial.

This year, a man in Perm, a city in the Urals, was fined 200 thousand rubles ($3,500) for reposting an article which correctly stated that the Soviet Union invaded Poland in 1939 in collaboration with the Nazis.

Russian textbooks have treaded a careful line when describing the Pact. But the 2016 edition of Russia’s most popular history textbook puts less emphasis on its secret protocols, in which the Soviets and Nazis carved up Eastern Europe among themselves, than ever before.

“It has a more justifying tone,” says Katsva. In fact, there is no word ‘aggression’ in the text. Instead, the book portrays the invasion of Eastern Europe by Soviet troops as a “liberation” from Poland and the impending Nazi invasion.

“On September 17, part of the Red Army was given orders to cross the Western border and liberate western Ukraine and western Belarus,” the text says.

The textbook gives a similar explanation for Russia’s military presence in the Baltic states. According to the authors, Russia’s invasion and annexation of the three northern European countries was the result of democratic parliamentary elections in the countries in which the communists in the Baltic States won.

“It doesn’t say anything about the fact that [the Baltics had] no choice,” says Katvsa, referring to the Soviet-installed governments in Baltic nations in June 1940.

Stalinist repressions?

The other most contentious episode which has divided Russians is Stalin’s role in the war. The new textbook admits the Stalinist repressions became “the central element of Soviet life” but devotes less space to them than previous editions.

“It is impossible to understand what happened in 1941 without the knowledge of the repressions,” says Abalov. Soviet troops were not-prepared for the Nazi attack because Stalin had purged the army on the eve of war.

But Katsva thinks the reason for glossing over difficult topics is that the USSR’s role in the war is supposed to inspire national pride. “Russia is not alone in glossing over the negative sides of its national memory,” he stresses. But the Kremlin has gone far further than that, turning Russia’s wartime memory into a political tool.

On the surface, it has worked. No other holiday sees the same crowds drawn onto Russian streets. But does Victory Day really unite Russians?

History teacher Abalov doubts it. “There is no single conception of the war,” he says, adding that there are no discussions about the human cost of the war. “The identity the government is trying to enforce on people is flawed,” he says.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.